CAAI Director Sanjog Misra and members of The Obama Foundation Leadership Network explored the applications of AI to value-driven work in private, nonprofit, and government sectors.

- By

- April 29, 2025

- Center for Applied Artificial Intelligence

With a shared vision to harness technology for social good, members of The Obama Foundation Leadership Network gathered for a panel discussion led by Dr. Sanjog Misra, Director of the Center for Applied Artificial Intelligence (CAAI). Working around the globe in private, nonprofit, and governmental roles with value-driven missions, Obama Foundation leaders raised interesting questions about implementation challenges in their own work, as well as the future of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in light of emerging regulations surrounding privacy.

Obama Foundation leaders brought diverse perspectives to the discussion, informed by their diverse work ranging from employment advocacy for incarcerated people to creating accessibility for children with learning disabilities, yet united by a shared interest of potential AI applications to their work.

THE EVOLUTION OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

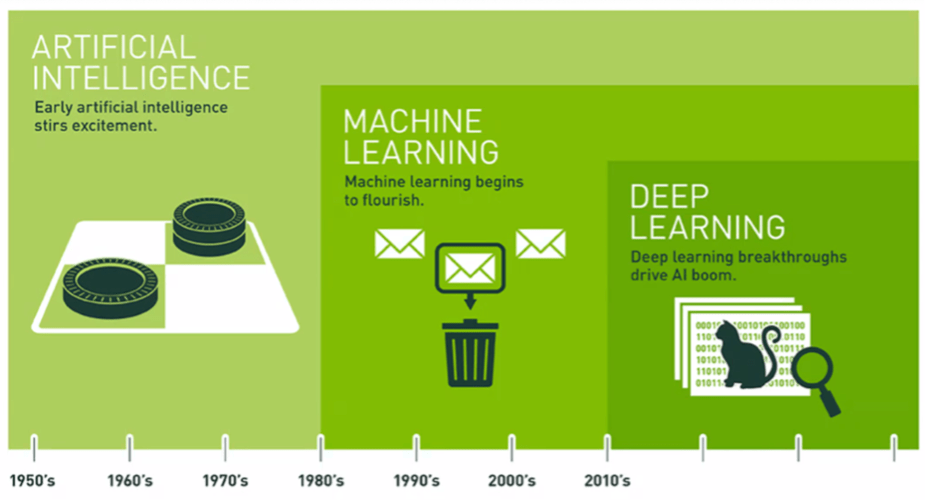

To set a common understanding, Dr. Misra reviewed the history and evolution of AI. He offered an early definition of AI set forth in the 1950s: “getting a computer to do things which, when done by people, are said to be intelligent.” An extremely simple chatbot followed; it was operated by ‘if-then’ statements and often shut down when prompted with more complex questions.

Then emerged the field of Machine Learning (ML), which encapsulates the tools and techniques that allow a machine to learn the processes to behave intelligently. The old idea was to teach a machine to featurize---to attribute specific features to objects. For example, attributes like pointy ears and fluffy tails were tied to the image of a cat. Now, images can be uploaded and ML models can construct the relationship between the composition of pixels and the output object.

More modern AI processes like Deep Learning have been modeled to mimic complex neural networks that fire in the human brain. This new era of biomimicry marks the emergence of artificial neural networks. The process is incredibly similar to the way children learn; they can be shown images which they then associate with specific words or objects. Each time a child is shown an image, for example of a cat, their association of the image with the real object and the written word strengthens. If the child looks at a puppy and calls it a kitten, they are corrected, and thus begin to understand what does or does not fit the pattern. The same learning technique is being applied to AI models.

The world expands from the simple example of a cat. Beginning with pictures, a model can evolve to understand words, videos, and can even be trained to drive a car. As the applications of AI grow, so does its access worldwide. AI is being used at all scales for a variety of corporate functions as well as integrated into government processes. It is on pace to disseminate across the world in about 5 years. “AI is moving faster than anything we have seen as a human species,” said Dr. Misra.

GENERATIVE AI

In 2014, yet another evolution of AI occurred with the development of generative AI. The quick progression of these models most closely resemble the familiar AI tools of today. At present, there is almost infinite generative power; nearly anything that a human can create is able to be machine-generated or imitated. Large Language Models (LLMs) such as Gemini and Chat-GPT are some of the most widely known applications of generative AI. Yet, what is less commonly understood is that they are fundamentally prediction models.

“[GPT-4] makes ____ up.”

Generative AI comes up with a series of outcomes with associated probabilities, then selects one to display. The caveat? Most outcomes are neither perfect nor entirely correct. But the model is not looking for accuracy, it is simply trying to predict the next word.

LLMs have now been trained on billions of words — nearly everything that is available on the internet and more. As a result, the number of connections in the machine’s deep neural network have been growing steadily. Going from millions to hundreds of millions to billions, a fascinating thing happened when the deep net hit triple-digit billions of connections: the model began operating beyond its training. Called emergence, generative AI has taught itself more complex processes like logical thinking, common sense, and theory of mind, the ability to attribute mental states to oneself and others.

Dr. Misra described his work using generative AI to personalize recertification reminders to SNAP recipients in the state of California. The SNAP program is a government instated program offering nutrition to millions of eligible, low-income individuals and families. To continue receiving benefits, recipients must fill out a recertification application every year. Failure to recertify leads to a loss of benefits, an all too common occurrence.

The participants were receiving generic reminders with some improvement in recertification rates. Dr. Misra and his team designed an AI-driven solution to personalize the messaging for each recipient based on what they would respond to best. Using algorithms Informed by communication theory and implemented via deep learning the team tailored each recertification reminder to nudge participants into action. These algorithmic nudges obtained meaningfully large improvements in recertification rates.

The experiment successfully secured $4.5 million for low-income Californians; individualized messages have the potential to ensure millions of SNAP dollars are allocated to communities across the country. The SNAP project was a particularly salient application of generative AI in the social welfare sphere. What remains to be seen is how AI can be scaled up to serve the entire U.S. population.

AGENTIC AI

This year has ushered in yet another new era, that of agentic AI. These models interact with the physical world and have the agency to take action (i.e., negotiation, receiving phone calls, answering messages). With a host of new applications, there is a need to think carefully about the ethics of the broad use of AI. There exists a trade-off between welfare and privacy: implementing AI-driven solutions large enough to serve an entire nation requires access to personal data.

In Dr. Misra’s project with the SNAP program, understanding consumer choices and each person’s response sensitivity was necessary to properly tailor messaging to each recipient. This balance must be weighed when implementing AI-driven solutions, a decision which Dr. Misra calls us to think more carefully about. It is possible to build privacy protection interventions, guaranteeing how data will be used and protected. To implement solutions, there must be some willingness to share private information; the question for regulators is where, how, and to what extent.

Establishing a common history on AI and his own use cases for social benefit, Dr. Misra opened an enriching exploration as to how The Obama Foundation Leadership Network can advance their own mission-driven work with the integration of AI both on a day-to-day level and on an organizational scale.