Representing four distinct disciplines, the 2016 Distinguished Alumni Award winners exemplify the resounding impact of Chicago Booth.

- May 01, 2016

- Leadership

Since 1971 we have celebrated innovative leaders across all industries, from finance to the arts, manufacturing to public service, and beyond. The Distinguished Alumni Awards honor individuals who continue to challenge and change the world we live in, exemplifying the resounding impact of Chicago Booth. Though they represent four distinct disciplines, our winners share a passion for forging new territory. Each has found a way to buck convention and create new opportunities through bold ideas and a clear vision for lasting impact.

Founding chair

Citizens United for Research in Epilepsy (CURE)

Susan Axelrod, LAB ’70, MBA ’82, didn’t go looking for her career; it came knocking on her door when her seven-month-old daughter was diagnosed with epilepsy. As she and her family grappled with her daughter’s condition, Axelrod also saw the bigger picture and realized through connecting with other families that something more could and should be done.

A trailblazer in an under-served field, Axelrod not only put a public spotlight on a little-understood disorder, she brought together scientists, medical professionals, and families in pursuit of innovative treatments and a cure.

Since Axelrod launched the organization, in 1998, CURE has been at the forefront of epilepsy research, raising more than $43 million to fund research and other initiatives focused on a cure for epilepsy. CURE funds grants for young and established investigators and has awarded more than 190 cutting-edge projects in 15 countries to date.

“We are the risk takers in the epilepsy research space. We’re diligent about what research we fund. We have an extensive review process, but we give priority to new, innovative, and cutting-edge ideas, because that’s the only way we’re going to change things.”

— Susan Axelrod

Early on in his career, Daniel P. Caruso, ’90, rode the boom and bust of the dot-com industry in the 1990s and the telecom meltdown during the first decade of the 21st century. With a level head, Caruso navigated the complexities, avoiding the traps that ensnared many of his colleagues.

Caruso was one of the founding executives of Level 3 Communications, which he helped start in 1997. He then served as president and chief executive officer of International Communications Group. He took the near-bankrupt company private and, in 2006, when Level 3 purchased ICG, Caruso cashed in on the opportunity to start his own new venture.

Caruso’s company, global communications infrastructure services provider Zayo Group, has developed a contrarian point of view, understanding that the real value of fiber networks is their long-term durability as the fundamental infrastructure of big data and the cloud. Zayo Group now connects thousands of office buildings, hundreds of data centers, and dozens of cloud destinations to a high-speed communications network.

“One of the biggest ways Booth helped me throughout my career—particularly at the more difficult times—is in having taught me the analytical and fundamental foundation of true value creation. Not the illusion of value, not chasing the latest idea or fad, but really building something that is a long-term platform for intrinsic value creation.”

— Daniel P. Caruso

After selling Braintree to PayPal in 2013, founder Bryan Johnson, ’07 (XP-76) looked back at the deal not merely as an achievement, but as the start of a new adventure. He set out to launch the OS Fund in support of “the world’s most audacious” scientists and entrepreneurs who are working to rewrite the operating systems of life.

Johnson’s defining belief is that we’re at a uniquely exciting moment in the story of humanity, because we can now literally create any kind of world we can imagine. He combines business acumen with an insatiable imagination to fuel all his endeavors, including writing a children’s book.

The OS Fund’s investments range from synthetic biology and artificial intelligence to energy storage and next-generation transportation. To create a more robust ecosystem for investors looking to fund entrepreneurs in these fields, the OS Fund developed a decision-making model it then open-sourced to help others better understand the risks and potential of promising sci-tech companies.

“I invest in future-literate entrepreneurs, which I define as those who create mental models for the emerging future while living experimentally and adventurously. They’re working on any one of humanity’s most audacious challenges or opportunities, and aiming to improve the lives of billions of people for generations to come.”

— Bryan R. Johnson

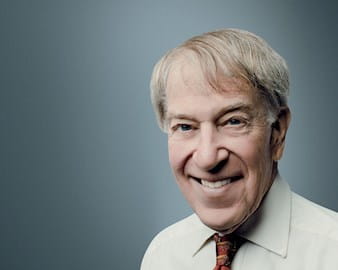

Roger C. Altman, ’69, began his investment banking career at Lehman Brothers and became a general partner of that firm in 1974. Beginning in 1977, he served as assistant secretary of the US Treasury for four years.

In 1987, Altman joined the Blackstone Group as vice chairman, head of the firm’s advisory business, and a member of its investment committee, with primary responsibility for Blackstone’s international business.

Beginning in January 1993, Altman returned to Washington to serve as deputy secretary of the US Treasury for two years.

With a unique vision, Altman launched investment banking advisory firm Evercore in 1995, guided by the idea that clients would be better served by advisers who were not tethered to the demands of a multiproduct financial institution.

Altman’s appetite for constant growth coupled with his continued ability to succeed in new directions is proof of his resiliency, curiosity, and entrepreneurial acumen. With a long career spanning five decades, he remains invigorated by his work.

“Leadership in my experience is a subtle mix of elements. There’s a fine line between waving a sword and saying we’re going up that hill, and on the other hand having an approach that builds support among your employees and your teammates so that you’re not an autocrat. Autocrats—at least in what I've ever seen—don't last too long.”

— Roger C. Altman