Jason Brown, ’09, describes his mother as an absolute powerhouse. With just a high-school education and waitressing experience, she built her own aesthetician business while single-handedly homeschooling and raising Brown and his brother. Organized, disciplined, and intelligent, she’s the hardest-working person Brown knows. Yet somehow, it wasn’t enough.

“Things were tight,” Brown says. “We never starved, but sometimes business wasn’t as good, and there would be no money in the grocery envelope.” They might eat beans and rice for weeks, or go without milk. They had no health insurance, so his mother constantly worried about them getting sick or injured. “I just saw the incredible stress she was experiencing.” That anxiety was a constant in their lives. How much would it take to pay the bills and still have something to eat? How could she budget just carefully enough?

It’s a tightrope that many Americans know all too well. To cope, many turn to credit cards, but that just exacerbates their stress. In October 2020, a study in the journal Aging & Mental Health found that one-third of consumers who had credit-card debt said it negatively affected their standard of living, and one in five said it harmed their health. According to a survey by NerdWallet, 41 percent of Americans who have debt feel anxious—and 35 percent feel overwhelmed.

“It’s the most complex financial problem that a normal middle-class American is going to deal with,” says Brown. “The interest rates are exorbitant, and they’re way higher than they need to be to cover the risk of the actual borrower.” Too often, it comes down not to how hard you’re working, but to whether credit-card companies are exploiting you, and whether you can figure out the difficult calculations of how much to pay and when, Brown says.

A recent survey from Bankrate showed that 46 percent of credit-card holders are carrying debt from month to month. And that’s getting worse amidst high interest rates, inflation, and the rising price of groceries. Many assume that credit-card debt comes from frivolous spending—but in reality, people end up leaning on their cards to pay for medical bills, car repairs, and other essentials, and according to a survey done by GOBankingRates.com, one of the most common reasons for missing a payment was needing to pay for food or groceries.

When Brown discovered the intricacies of this issue as an adult, he thought of his mother and her stress as they grew up. What if he could have spared her some of the financial anxiety she went through?

“I wanted to build a software-based system that could do most of the financial thinking and work for a normal person,” says Brown. “And I wanted to start by building a robot that could take on the responsibility of managing a person’s credit cards, to save them money on interest and help them get out of debt.”

“It's the most complex financial problem that a normal middle-class American is going to deal with.”

— Jason Brown

Credit-card companies charge exorbitant rates even for people with good credit scores, Brown says, and they take advantage of people’s forgetfulness and struggles to budget.

Tally, the San Francisco–based consumer tech company of which Brown is cofounder and CEO, takes on responsibility for users’ credit-card debt through a credit line that they can get from banks for lower rates. Then users can pay Tally one easy payment monthly instead of figuring out how best to pay their many credit cards down. They no longer have to worry about late fees, unpaid balances, or juggling and calculating interest rates—Tally does it all for them. That makes it easier to pay down their debt.

In the 2021 revised edition of their game-changing book Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness, Richard H. Thaler, 2017 Nobel laureate and the Charles R. Walgreen Distinguished Service Professor of Behavioral Science and Economics, and Cass R. Sunstein, founder and director of the Program on Behavioral Economics and Public Policy at Harvard Law School, cite Tally as a prime example of how to use behavioral science to fix the problem of credit-card debt.

“While auto-pay can solve the memory problem,” they write, “an even better strategy would be to turn over the management of credit-card debt to someone who will both do the math and not be forgetful. As they say, there is an app for everything, and this is no exception. An app we particularly like is called Tally.”

They aren’t the only ones who like the app. Tally recently raised an $80 million Series D round of funding. Forbes included it in its Fintech 50 list and named it a Next Billion-Dollar Startup in 2020. Tally was also named a Most Innovative Company by Fast Company in 2019 and 2021, and received a Smart Money Award by REAL SIMPLE in 2020. And Brown is just getting started.

Respecting the Grind

When Brown was 12, every now and then his mother would buy them an avocado—an unspeakable luxury. He would eat it with a sprinkle of salt.

“One day,” his younger self thought, “I’m going to be rich enough to eat as many avocados as I want.”

Brown was already working as a teen—pouring concrete and selling menswear at factory outlets—to help his mother support their family. At Boston University, he worked multiple jobs to pay tuition. “I didn’t get to just be in school,” says Brown. “I was working 100 hours a week while attending college full time.” But when his finances weren’t adding up, he decided to spend his summer break going door-to-door persuading people in his hometown to hire him to paint their houses.

He made so much money that first summer that he paid for two and a half years of school—and was able to scale his single-person endeavor into a full-fledged company. By the time he graduated, the business had 400 employees. He was able to graduate without debt—and with enough money to buy a condo. He wasn’t rich, but to him, it was unbelievable wealth.

“From that point on,” he says, “I knew business was the future for me.”

Brown cofounded subscription-based tech support company Bask.com in 2004—just two years after undergrad—and sold it in 2007, before entering business school.

“I had all the scrappiness and intuition for how to build a business, as well as the actual mechanics, but I knew I was missing some understanding of the form,” he says. “I wanted to refine my knowledge and sophistication around how you build and finance a business.”

At Booth, he met Jasper Platz, ’09. They co-chaired the Chicago Booth Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital Club, splitting it up from the private equity club and aligning closely with the Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation at the University of Chicago. They went on to found Gen110 together—a consumer debt product market that finances residential solar installs. It was acquired by Solar Universe in 2013—at which point Platz and Brown came together to cofound Tally.

Brown loved Booth not only for the community and network that he clearly thrived in, but also for the academics themselves. He craved the rigor, and enjoyed his classes. “It was the perfect marriage of what I had already, the applied experience, and getting to understand the why behind things.”

High Leverage

Standing in front of one of Tally’s first big potential investors, Brown flashed back to a course he had with James E. Schrager, clinical professor of entrepreneurship and strategic management.

Schrager told the class about a manufacturing company, the Marmon Group, he studied as a PhD student, and how he took on the work of turning around a small factory. Schrager noticed there that brief, unplanned encounters—whether with factory employees or the CEO of the conglomerate—could be pivotal to how people saw him moving forward. The moments usually weren’t the planned presentations he had worked so hard on. The tough questions asked afterward, or even the casual encounters and spontaneous conversations on the factory floor—those had outsized impact on whether people were ready to sign on to his plan or not.

“Careers and deals are often made in brief moments of intense leverage,” Schrager summarized to his students, including Brown. “Will you be ready when your moment comes? Or will you watch it pass by?”

This, Brown realized, was one of those moments. He had one hour to get his investor to understand a concept that had never existed before—and to get her to write a $2 million check for a 10-slide deck.

“My entire life—who I was, how I grew up, going to Booth, all of it funneled into this one hour of being able to communicate both the emotion behind Tally and the raw math and finance concepts behind it,” Brown says. “I think about that Schrager quote often. When people think about their career, those moments are the ones that matter, and you have to be ready for them.”

Tally, in some ways, was a tough sell. But venture capital firms including Kleiner Perkins and Andreessen Horowitz could see the potential. “They saw that we weren’t trying to build a tool,” says Brown, that “we were trying to build an A.I. that would be able to, by itself, save people money. They were forward leaning enough to see that this new experience that hadn’t existed before—a new interaction model between humans and finance—was something worth putting money behind.”

“My entire life—who I was, how I grew up, going to Booth, all of it funneled into this one hour of being able to communicate both the emotion behind Tally and the raw math and finance concepts behind it.”

— Jason Brown

Armed with the network he and Platz had built at Gen110 and Booth, and with the knowledge and mindset they’d taken away from their courses, they were able to raise $120 million in investment over several rounds in order to have an operational app that was ready to launch by 2019. As of December 2022, Tally had paid almost $2 billion in credit-card debt for its members.

“There is no alternative to Tally in the marketplace,” says Brown. “People can take out personal loans, do balance transfers, use spreadsheets—but there’s no app where they can pay the balance on and manage all of their cards in one place with automated guidance.”

Tally’s new goal is to expand availability across different platforms. Financial institutions and fintech apps have been approaching Tally, looking to embed it within their own products. Brown is hoping for more of these partnerships to help extend Tally’s reach.

“We have to make it so that if you have credit-card debt in this country, it’s a given that Tally takes care of your credit cards in order to save you money on interest, avoid late fees, and pay off your debt,” says Brown. “In the old days, you couldn’t imagine carrying your money around just in your hands—you needed a wallet. In this digital world, we want Tally to be that obvious.”

Living the Life

Today, Jason Brown is thriving both professionally and personally. Like his 67-year-old mother, who has run her business for 35 years and is a raw vegan who enjoys exercise, Brown carries focus and discipline into everything he does.

Brown makes sure to block half a day once a week—preferably in the morning, when he does his best thinking—for unstructured time to walk and then sit around and get bored. “Giving the brain some space allows it to think about things that aren’t tasks or rudimentary factors,” he says, which often leads to new ideas and breakthroughs.

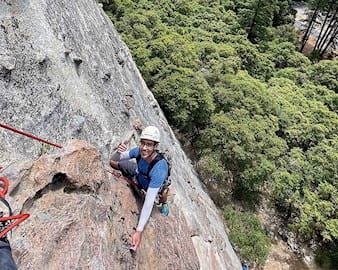

He’s an active person who enjoys sports such as rock climbing and cycling. His current obsession is free diving: a form of underwater diving that relies purely on breath holding, without the use of any gear. He’s been training for two years, and can hold his breath for more than five minutes and dive to a depth of 200 feet without mechanical support.

“I find it deeply meditative,” he says. “If you’re at 200 feet and get panicked, you’ll use up all your oxygen and will die. You have to get your body down to a place where you’re alert and focused, but calm.” It’s perfect practice for being ready for high-stakes situations like running a business—or parenting his two young boys with his wife, Natanya Marracino.

If he has one piece of advice for Booth students, it’s this: don’t think you need to get it all perfect on the first try. “I would encourage people who are looking to start something to be more OK with having bad ideas and proceeding with things that aren’t perfect or don’t have the exact market figured out,” Brown says. “Bad ideas can turn into good ideas once you start working on them. Move forward, put yourself out there, and you’ll figure it out as you go.”

As for the avocados he dreamed about when he was a kid? Brown laughs. “I try to have at least one a day.”