May 2, 2016: Historical Comparison Shows the Extent of Growth in Political Contributions from Big Donors

More than a third of total contributions raised by presidential candidates from both parties in the 2016 race come from donors who gave more than $5,000. At this point in the 2008 race, presidential candidates raised only $3.1 million from big donors.

The 2016 presidential election is widely expected to be the most expensive election in U.S. history. With campaign expenditures rising to unprecedented levels, evidence is pointing to a growing concentration among campaign donors, with fewer and fewer donors supplying a growing share of political contributions.

As part of the Stigler Center’s Campaign Financing Capture Index—a project tracking the attempts of large political contributors to affect public policy by focusing on the fraction of total funds raised from large donors—we compared the fundraising records of presidential candidates during the 2016 election cycle to candidates’ fundraising during the corresponding periods of the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections. The comparison shows the extent of the rapid growth in political contributions from big donors during the last eight years.

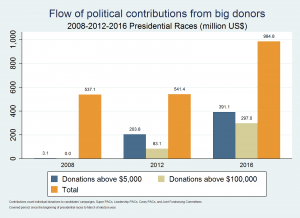

The Stigler Center’s analysis of the latest available fundraising filings from this election’s candidates shows that presidential hopefuls raised $391.1 million in donations above $5,000, and $297 million from donors giving more than $100,000 (as of late March). At this point in the 2008 race, presidential candidates raised only $3.1 million from donations above $5,000, and donations above $100,000 were virtually non-existent.

More than a third of total contributions raised by candidates from both parties during the 2016 election cycle have come from donors who gave more than $5,000. In contrast, $533.9 million out of the $537.1 million in individual contributions that were raised by presidential candidates through March 2008 came from donations below $5,000.

Political contributions from big donors in the 2016 election cycle are 91 percent higher than the large donations raised during the corresponding period in the 2012 presidential race. In March 2012, donations above $100,000 represented 41 percent of large campaign contributions –in the 2016 election this figure is currently at 76 percent.

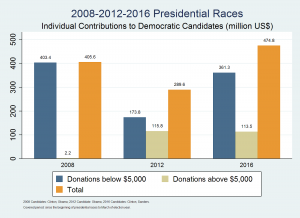

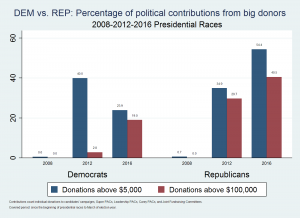

A comparison of the 2008, 2012 and 2016 races shows that the growing luster of big donors extends to both parties. During this election cycle, contributions above $100,000 account for 19 percent of donations to Democratic candidates, and 40.5 percent of donations raised by Republican candidates. During the corresponding period in the 2012 race, those figures were 2.8 percent and 29.7 percent, respectively.

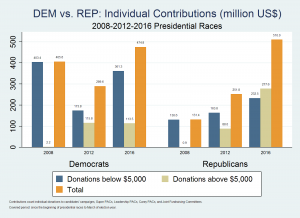

Among Republicans, donations above $5,000 now represent 54.4 percent of all contributions to presidential candidates.

At this point in the 2008 race, donations above $5,000 represented less than 1 percent of contributions to presidential campaigns in both parties. From the beginning of the race through March 2008, Democratic presidential candidates raised $403.4 million from donors giving less than $5,000, and $2.2 million from large donors. In the 2016 election cycle, they have raised $113.5 million so far from large donors, and $361.3 million from donors giving less than $5,000.

Among Republicans, the picture becomes more skewed. At this point in the 2008 race, Republican presidential candidates raised only $900,000 from large donors giving more than $5,000 (less than the Democrats). In 2012, this number grew to $88 million (still much less than Democrats). In the 2016 cycle, Republican candidates have raised $277.6 million from large donors, surpassing the $232.5 million they raised in donations below $5,000 and outpacing Democrats among large donors.

The Campaign Financing Capture Index analyzes the distribution of political contributions to presidential candidates and takes into account individual contributions and contributions made to the PACs, super PACs and joint fundraising committees that support each candidate. The idea behind the index is that large political contributions represent more than the mere expression of political preference, and are more likely meant to influence policy in favor of the donor’s interest. When the percentage of funds raised from large donors is significant, as it has been in recent years, this problem becomes acute.

Is Citizens United to Blame? Yes and No

In the six years since Citizens United, the ruling in which the Supreme Court overturned the limits on corporate political spending has often been portrayed as the main catalyst for the explosion in political spending. However, some of the problems relating to campaign finance predate Citizens United. A recent analysis of FEC data by The Economist found that since 1980, Democratic and Republican primary candidates who went on to win their party’s nomination have raised an average of 74 percent of campaign money from large donors, whereas candidates who relied on small donors tended to end up on the losing side.

Is Citizens United the main culprit behind the recent surge in political spending? According to Harvard Law School professor John Coates, Citizens United is an important factor, but its impact is a little more complicated to decipher than some make it out to be. “Citizens United was a trigger. It’s complicated to trace its impact, because literally-speaking, the holding of that case doesn’t even apply to contributions– it applies to independent expenditures. There’s a subsequent case that interpreted it to also extend to super PACs. At the same time, Citizens United is about corporations, and the numbers we’re seeing are coming presumably from individuals,” says Coates.

“However, I do think there’s an impact, and the impact is largely the court signaling that restrictions on campaign finance were suspect, in the context of that case, pushing Republicans even further right. Prior to that case, Republicans had been very much in favor of disclosure regulations, as a way of saying ‘we’re not in favor of more restrictions, we’re only in favor of disclosure.’ But after the case they sort of won the battle on restrictions, so they now fight disclosure too,” he adds. “There are rules in place about coordination between super PACs, parties, individuals and individuals candidates, but they are totally unenforced, because the Federal Election Committee is split 3-3 between Republicans and Democrats and, partly as a result of Citizens United, it’s become more polarized.”

Democrats, says Coates, also bear some responsibility. “The Democrats are not totally innocent. They have really put effort into trying to undo Citizens United only belatedly, especially in Congress, and really haven’t made it a focal point of their own internal priorities. I think a lot of Democrats were happy with the idea of running against Republicans on campaign finance, that is, they didn’t really want to fix the problem–they wanted to preserve the problem so they can run on this issue.”

Many politicians who receive money from super PACs claim that large donations do not affect their decision making, and despite the immense growth in political spending in recent years, many academic researchers encounter difficulties when they search for empirical evidence that campaign contributions influence legislation. Some succeed (see Powell 2012), but overall, most scholars tend to see campaign contributions as having little influence over policy.

According to Coates, this is partly due to what he calls a “research design problem.” He adds: “Another thing is that we have many, many vetoes in the political process. Some of the most effective money flows to people who are in a position to block something from happening, which is going to be harder to find evidence of, because by definition you’re preserving the status quo. You have to have some benchmark to measure what would have happened had the veto not been exercised. There are some studies that do find evidence of policy impact. These tend to be in places where the money is flowing to a committee chairman, or to specific influential members.”

Also, he says, part of the problem might be that there are relatively few studies of state law. “In the U.S., many policies are made at the state level, especially initially, and then you have a norm around a particular policy position, and that influences the federal debate.”