Where China’s Stimulus Program Went Wrong

- By

- March 15, 2017

- CBR - Economics

When recession threatened to devastate even the richest economies in 2008, global leaders cheered China’s announcement of a bold and expensive stimulus plan as a stabilizing factor in a world of quickly declining fortunes. Global financial markets rose, and leaders at the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund praised the development.

Nearly a decade later, disappointment is setting in. Economic growth in China and worldwide remains sluggish, and a potential debt crisis in China threatens to thwart progress toward recovery.

One problem is that most of China’s stimulus money went to state-controlled companies that were less productive than privately owned businesses, according to research by Chicago Booth’s Lin William Cong and Jacopo Ponticelli. These more-productive companies had been chiefly responsible for fueling Chinese economic growth before the 2007–10 financial crisis—but were disproportionally allocated less bank credits during the stimulus program, say the researchers.

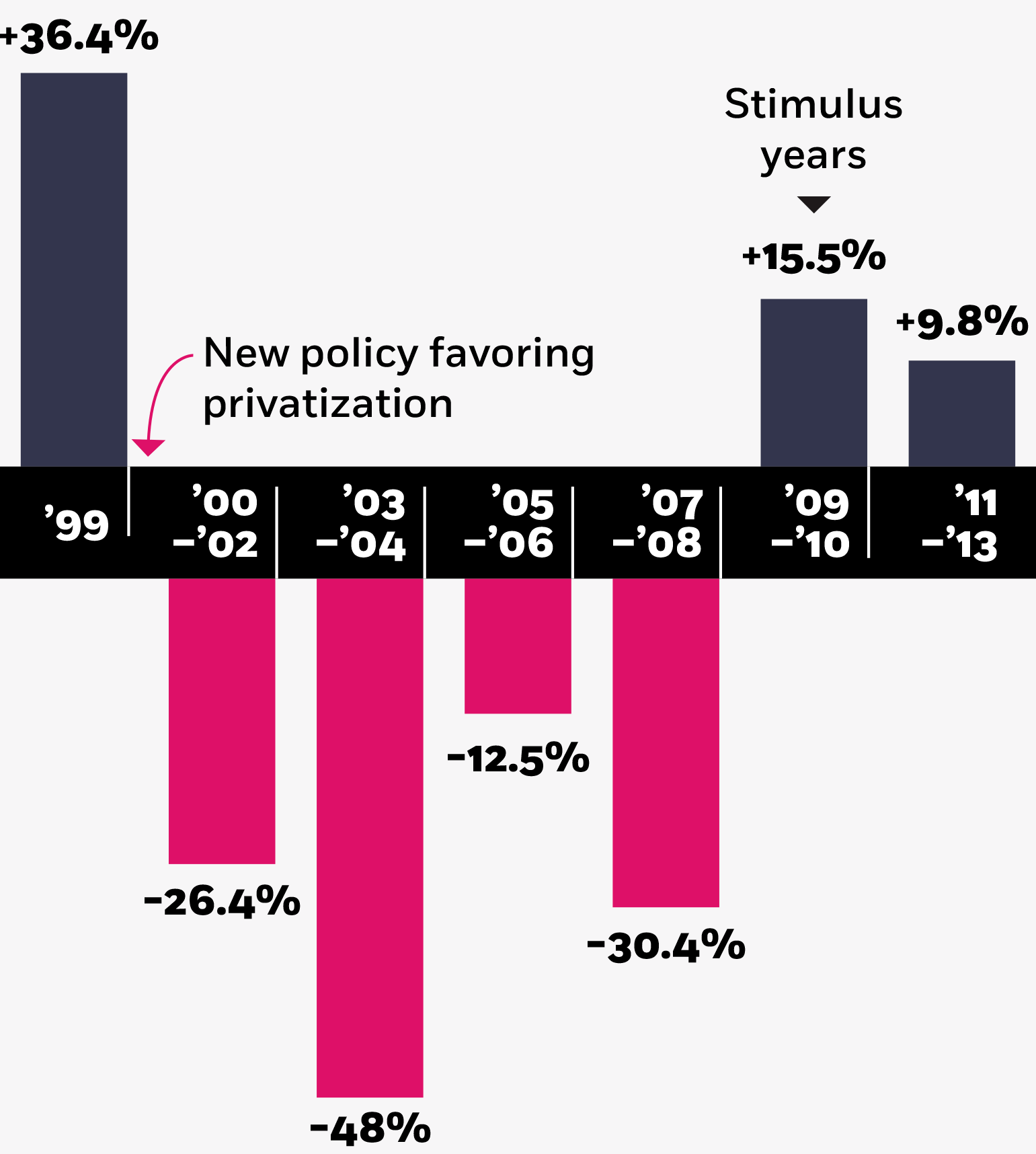

Loans for China’s state-owned companies

Percentage difference in levels of new loans vs. private companies, as a share of revenues

Cong and Ponticelli, 2017

China’s stimulus package prominently featured a two-year fiscal program that involved spending about 4 trillion RMB—a figure that equated to almost 13 percent of China’s GDP at the time—on national infrastructure and social-welfare projects as a way of averting massive unemployment and economic depression.

Unlike stimulus programs in the United States and other Western countries, which were mostly funded through government debt, China funded the bulk of its program by introducing a set of bank-credit-expansion policies—and the study brings attention to the unintended consequences in terms of allocation of new bank loans of this component of China’s stimulus that is often neglected by researchers and media. New bank lending jumped higher, and total credit in the economy grew by 30 percent in 2009 alone, according to the researchers.

China’s corporate debt level was estimated at 170 percent of GDP last year. This has led to fears its banks could face massive loan defaults as corporations struggle to repay their debts in a weaker economic climate.

The study produces evidence to support these concerns. Using data from individual public and private companies, the researchers find that during the two years of the stimulus plan (2009 and 2010), a smaller percentage of loan money for building businesses went to skilled entrepreneurs than it had in the past. Rather, the majority of business lending shifted to firms with lower productivity but closer connections to government.

The less-efficient companies that now hold most of the stimulus debt may not be capable of generating stronger economic growth for the country. Without a better economic climate, such companies could find it difficult to service their loans.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.