When Republicans in Washington, DC, started talking up the latest round of tax reform, they said they were aiming for something so simple that 90 percent of US households could essentially file their taxes on a postcard. US Representative Kevin Brady (Republican of Texas) held up a prop, a mock-up of such a tax postcard, to drive the point home.

And simplifying the tax code ostensibly has bipartisan backing. Both the Bush and Obama administrations advocated for simplification, in reports, as have House Speaker Paul Ryan (Republican of Wisconsin) and Senator Elizabeth Warren (Democrat of Massachusetts). But when the Senate passed a tax bill this past December, there was no postcard. Instead, Democrats pointed to handwritten notes in the margins of the bill as a sign of a madcap construction process going on. Proposals to cut deductions for home mortgages and medical expenses, and tax credits for adoption and education, had been met by pushback. “File Your Taxes on a Postcard? A GOP Promise Marked Undeliverable,” pronounced a New York Times headline shortly before President Trump signed the bill.

What happened? The same thing that always does, suggest researchers. While simplicity is a stated goal, complexity wins the day. Hence companies and individuals will hire accountants to wade through the latest bill, interpret the new rules, offer guidance, and help work through the inevitable corrections and amendments.

And this comes at an economic cost. Research by James Mahon and Chicago Booth’s Eric Zwick, and others, collectively indicates that the complexity leads individuals and companies to fail to take advantage of billions of dollars in offered breaks, many of them presumably intended to stimulate the economy. In this way, complexity undermines what tax incentives are purported to accomplish.

The tax-reform cycle

The US tax code is a master class in convolution. Individuals are taxed at different rates, and they can reduce their effective rate through myriad credits and deductions, which take time to itemize if they choose to do so. Companies’ stated tax rates depend on their structure, and companies, too, have opportunities to change their effective rates.

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 memorably promoted simplicity as one of the three core reasons for pursuing a system overhaul, the others being efficiency and fairness. According to a 10-year analysis of the act by University of California at Berkeley’s Alan J. Auerbach and University of Michigan’s Joel Slemrod, the act “had mixed success in reducing complexity.” It registered some clear wins, such as nearly eradicating the tax-shelter industry, and temporarily eliminating the tax differential between capital gains and ordinary income, “which many tax lawyers had argued was the largest cause of transaction complexity in the pre-TRA86 tax code,” the researchers write. But other changes fell flat. Taxpayers kept paying for professional tax assistance, an indicator of the code’s complexity.

Since then, the calls for simplicity have continued. Some call for simpler but more regressive tax structures such as a retail-sales tax, a value-added tax (which levies a tax at every stage of an item’s production and distribution), or a flat tax that would give all individual taxpayers a single rate. But to date, tax reform has never reversed the complexity trend. Other than the 1986 act, “I am not aware of any other major tax legislation that had simplicity as a stated objective, which makes it unlikely that simplification resulted,” says Auerbach. “Indeed, the general movement over the years toward using the tax system to accomplish various policy objectives, through the use of so-called ‘tax expenditures,’ has led to greater complexity.”

Walking away from billions

What’s making the code so convoluted? As Auerbach notes, politicians have taken to using tax breaks to encourage employers to hire more people (or at least not fire them), buy equipment, and otherwise invest in creating jobs. They use other breaks to push people to pursue education that would raise their wages, borrow money to buy a home, and send children to day care while parents work. When these incentives function as intended, more money flows into the economy through rising wages and spending, which generates more funds for the US Treasury at tax time.

But tax breaks only change behavior if people claim these breaks—and many don’t. The Internal Revenue Service notes that one in five eligible workers doesn’t take advantage of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a program that tax-policy groups consider effective for pulling low-income families out of poverty. And, according to the Brookings Institution, there are only “relatively modest” take-up rates for the Saver’s Credit, the Child Tax Credit, and the American Opportunity Credit, which is up to $2,500 cash toward college tuition.

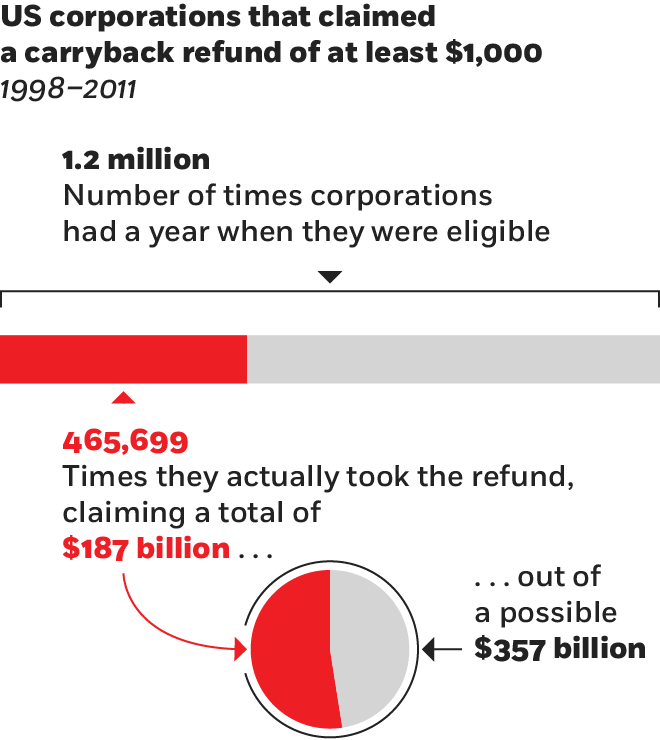

Mahon and Zwick find that companies, too, are leaving money with the government. They look at the carryback, a permanent tax break in the US code designed to act as an ongoing economic stabilizer. The carryback lets companies claim refunds for net operating losses, which ostensibly encourages healthy companies to continue spending and employing people during rough years. Most US corporations have been eligible for carryback refunds at some point.

Congress twice beefed up potential carryback payments specifically to stimulate the economy in recessions, and many companies took advantage of the relief as intended. In one example, during fiscal 2010, a particularly dire time for many American manufacturers, Applied Materials collected $130 million for the carryback of heavy losses recorded in 2009, the researchers note. The company went on to grow dramatically, perhaps aided some by the tax relief.

When a refund might not be worth it

Companies let the government keep billions of dollars in carrybacks, which are tax breaks benefiting those with net operating losses.

Mahon and Zwick, 2017

But these tax-break expansions could have helped many more corporations than they did, particularly during the Great Recession, according to Mahon and Zwick. The researchers culled 1 million corporate tax filings from 12 million companies between 1998 and 2011. Each filing in their sample was eligible for at least one carryback claim of at least $1,000. In 2008 and 2009 alone, US corporations were eligible for $124 billion in carryback refunds but claimed only $68 billion.

Only 37 percent of corporations eligible for refunds claimed them, the researchers find. Thousands of companies didn’t file claims, leaving $170 billion in potential carrybacks unclaimed. Eligible carryback claims for the period totaled $357 billion between 1998 and 2011, according to the study, but only $187 billion in claims were collected.

For many companies, the size of the claim didn’t appear to be a deciding factor. The take-up rate rose with the relative value of the claim, but only the very largest corporations had take-up rates exceeding 50 percent. Companies big and small left money unclaimed. Of only the larger companies eligible for refunds of more than $100,000, one in four didn’t pursue the claim. For small and midsize companies eligible for refunds of more than $10,000, half of the refunds went unclaimed.

The companies that opted out of a carryback claim didn’t do so in order to get some other cost benefit, such as from carrying forward losses, the research finds. They simply let the government keep their money. Even after allowing for the expenses involved in paying professionals to file a claim, the value of the carryback exceeded the cost for most refunds in the study sample.

Why complexity is at fault

The researchers reason that complexity must have caused the companies to leave all those billions unclaimed. For one thing, companies that had sophisticated accounting help were more likely to claim a carryback.

Filing a carryback claim takes an average of 16.5 hours, according to IRS data used in the study. Much of the time is spent figuring out how much can be collected. The process includes filing a form to document how the refund was calculated, which essentially requires redoing past tax returns.

More-complicated past returns are more likely to require additional computations, which leads to a higher likelihood of more interaction with the IRS, related either directly to the carryback claim, or to past returns that are otherwise under audit. IRS audits, which occur annually for large companies and are common at smaller ones, can take years to clear. Disputes over carryback claims alone can take years to resolve.

Companies that hired certified public accountants and attorneys to prepare and file their taxes were more likely to file carryback claims. Compared to a 37 percent claim rate for all eligible filers, 42 percent of eligible companies that hired an outside attorney filed carryback claims, and the figure was 45 percent for companies that hired CPAs.

And more sophisticated preparers also seemed more likely to file claims. Older preparers and accountants who had bigger client bases were more likely to seek carryback refunds. Preparers who worked for themselves were less likely to.

Taxpayers underreact to or even ignore new tax laws when incentives are complex, even when the potential gains are high.

Big companies generally hire sophisticated preparers, so Mahon and Zwick studied claim patterns of smaller companies that were both eligible for multiple carryback claims between 1998 and 2011 and had switched tax preparers during these years. To minimize the possibility that a corporate management change led to changes in tax strategies, the researchers focused findings on switches that occurred when the tax preparer either died or moved at least 75 miles away.

The researchers conclude that characteristics of the tax preparer mattered as much to the decision to file a carryback claim as intrinsic characteristics of the company itself, such as asset and loss size. More sophisticated preparers—which the researchers identified in part as those who had more official training, experience, and clients—filed more claims.

Meanwhile, large companies’ actions were also affected by tax issues not directly related to carryback claims. Companies that paid the corporate alternative minimum tax, for example, were considerably less likely to claim a carryback refund. Technically, the alternative minimum has nothing to do with the carryback—it’s meant to ensure that profitable corporations pay some tax even after deductions, and it’s irrelevant for most small and midsize corporations. However, a carryback claim adds to the accounting time required for an alternative minimum filing. Separate accounts are required for regular tax and alternative-minimum calculations, including accumulated stocks of carrybacks, which can alter the ultimate size of a potential refund.

Thus the decision not to file carrybacks was driven not by the carryback provision itself, but by broader tax-code complexity, the researchers conclude. The companies that claim the alternative minimum may simply decide they don’t want to risk complications with this filing, or add to their accounting expenses, by also claiming carrybacks. And other companies only filed claims when sophisticated preparers guided them to do so.

Complications decades in the making

While Mahon and Zwick focused on corporations, other studies find that tax-code complexity also reduces take-up of provisions aimed at individuals. Taxpayers underreact to or even ignore new tax laws when incentives are complex, even when the potential gains are high, according to a 2015 study by University of Oxford’s Johannes Abeler and MIT’s Simon Jäger.

In an experiment run by Abeler and Jäger, each participant could earn a payment for sliding icons on a screen into position. One group was told they would receive a piece rate, and pay a steadily increasing tax, for each correctly positioned icon. A second group was given the same job with the same piece rate but with more-complex incentives and tax rules—they had 22 rules versus two. Before the task began, every study participant decided his or her optimal number of completed sliders.

New incentives, identical in each group, were added in subsequent rounds. Subjects who started with the more complex system were less likely to react well to the new incentives, and thus earned significantly less money, according to the findings. They were more likely to simply stick to their previous calculations of how to maximize their returns, even when the rewards for adjusting their productivity were large.

A separate study, published in 2015, finds that simplifying the information provided to potential recipients of the EITC greatly improved take-up rates. The refund is intended to support low-income earners, but as of 2005, roughly 6.7 million low-income taxpayers who could boost their take-home earnings with the credit did not claim it, leaving, on average, 33 days worth of pay with the government, note Carnegie Mellon University’s Saurabh Bhargava and University of Texas at Austin’s Day Manoli.

The researchers worked with the IRS to mail additional EITC information packets to 35,000 likely eligible taxpayers in California who had failed to claim the credit. Both the original and subsequent mailings contained worksheets that could be filled out and returned for refunds. There were a number of different experimental versions of the mailings and worksheets, one of which simplified the original two-sided, text-dense information sheet onto one page with larger font. The packet also included a simplified version of the original worksheet. A control group received a repeat of the original notices.

While follow-up notices of any kind boosted claims, a notice with a simplified layout significantly boosted take-up, the researchers find. “Small changes to the design and simplicity of these forms can induce large responses among otherwise intractable populations,” notes Bhargava. “The share who fail to claim these valuable benefits could be significantly reduced by clearer, shorter, and simpler forms.”

But current take-up rates indicate that the EITC has yet to fulfill its potential as a social-welfare tool that can help minimize poverty and promote a healthy economy. And the research collectively suggests that the effects of many tax incentives are likely muted. Forecasters—whether predicting the number of families who will collect food subsidies, or the number of jobs that a corporate tax break will create—generally assume that people and companies act in their own best interests, but if complexity prevents them from doing so, the benefits don’t have the intended effects.

This leads to a predictable cycle. When benefits don’t have the intended effects, lawmakers put more benefits and incentives in the code. Yet these additional benefits and incentives make the code more complex, so people and companies don’t claim them. And this further undermines what the benefits are there to do. But it leads to a clear takeaway: to effect economic change with tax laws, it would help to make the laws simpler.

This assumes, however, that economic change is the intended goal. “There is some argument for complexity,” says Stanford’s John H. Cochrane, who is also a distinguished senior fellow at Booth. “By making a tax advantage available but very obscure, the government can give it to a narrow group that really cares and count on others not figuring it out. . . . I call it price discrimination by needless complexity.”

What about that bipartisan support for simplification? Overstated, suggests Auerbach. The goal of a simpler code ranks “right up there with motherhood and apple pie,” he says, “as long as it’s an abstract objective.”

- Johannes Abeler and Simon Jäger, “Complex Tax Incentives,” American Journal of Economic Policy, August 2015.

- Alan J. Auerbach and Joel Slemrod, “The Economic Effects of the Tax Reform Act of 1986,” Journal of Economic Literature, June 1997.

- Saurabh Bhargava and Day Manoli, “Psychological Frictions and Incomplete Take-Up of Social Benefits: Evidence from an IRS Field Experiment,” American Economic Review, November 2015.

- ———, “Why Are Benefits Left on the Table? Assessing the Role of Information, Complexity, and Stigma on Take-Up with an IRS Field Experiment,” Advances in Consumer Research, 2012.

- Esther Duflo, William Gale, Jeffrey Liebman, Peter Orszag, and Emmanuel Saez, “Savings Incentives for Low- and Moderate-Income Families in the United States: Why Is the Saver’s Credit Not More Effective?” Journal of the European Economic Association, April–May 2007.

- James Mahon and Eric Zwick, “The Costs of Corporate Tax Complexity,” Working paper, February 2017.

- US Department of the Treasury Office of Tax Policy, “A Comprehensive Strategy for Reducing the Tax Gap,” September 26, 2006.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.