Successful entrepreneurs are good at sales, even when they have no previous experience or formal training. Timothy Butler, a senior fellow at Harvard and cofounder of the career self-assessment company CareerLeader, found evidence to support this stereotype while analyzing psychological-testing results of more than 4,000 successful entrepreneurs and comparing them to those of 1,800 business leaders. Butler assessed successful entrepreneurs on leadership dimensions rather than entrepreneurial characteristics, and he has company: a growing body of research is uncovering overlap as well as critical differences between highly effective entrepreneurs, salespeople, and leaders.

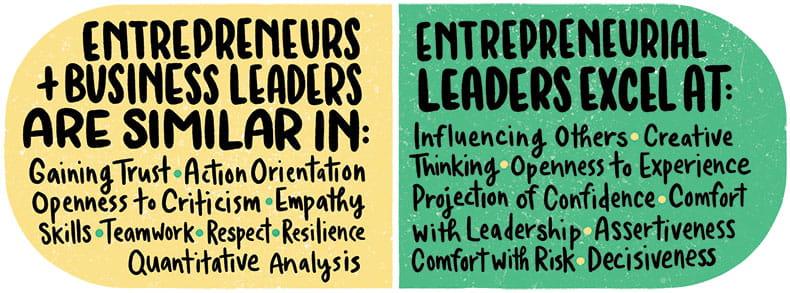

Let’s start with Butler’s work, which focuses on 41 dimensions of leadership developed through years of research at CareerLeader with cofounder James Waldroop. Their model looks at leaders’ traits, skills, and interests—placing interests rather than competency at the center of career development. In this context, an analysis Butler did using self-assessment and data from 360 reviews finds that on 28 of the 41 dimensions, successful entrepreneurs looked basically the same as other business leaders.

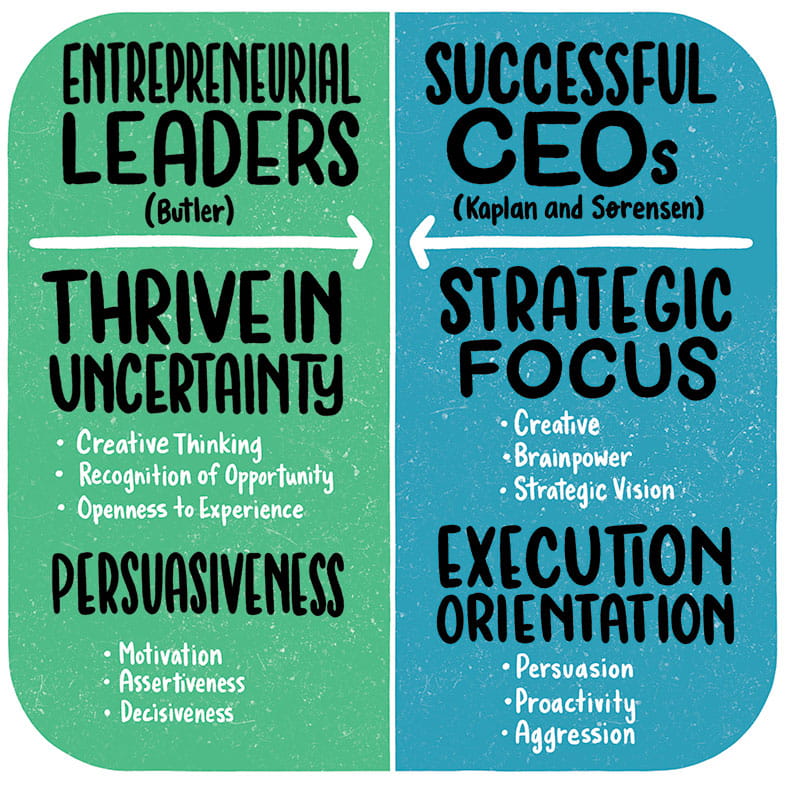

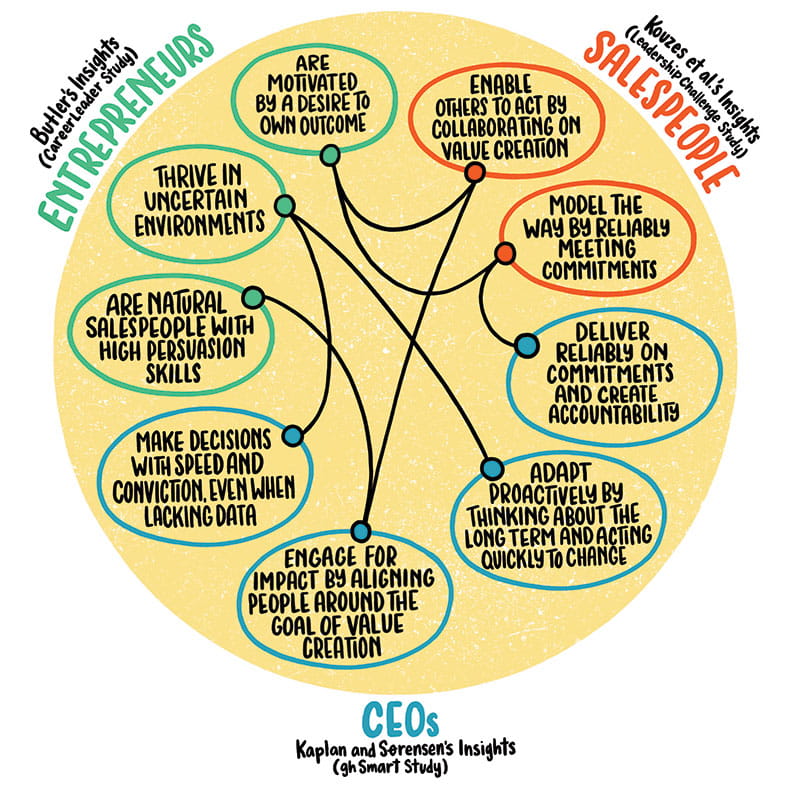

However, the same analysis suggests that entrepreneurs have three significant distinguishing characteristics. First, they have a strong desire for control in their careers. They want to own their company’s processes end to end. Because they score high on an interest in enterprise control, and on an interest in influencing others, entrepreneurs can be defined first by their interest in control, Butler concludes. Second, entrepreneurs have a greater confidence in their ability to thrive in uncertain, ambiguous situations—indicated by more openness to new experiences, creative thinking, ability to identify opportunities, and comfort with risk—than typical business leaders have. Finally, entrepreneurs possess a natural ability to sell—to persuade others to buy into their visions, join their teams, invest in their companies, and ultimately buy their products. The entrepreneurs in CareerLeader’s data set demonstrate high levels of confidence, assertiveness, and decisiveness, as well as great communication skills and confidence in their ability to effectively influence others.

Butler’s work validates the stereotype that entrepreneurs are natural salespeople. But this validation also raises the question: Is this connection a correlation or a cause? Are entrepreneurs good at both leadership and sales, or are they successful at selling because they have these leadership skills?

Sample of CareerLeader’s 41 dimensions of leadership

What helps entrepreneurs sell

Research from Deb Calvert, founder of business-and-sales-coaching company People First Productivity Solutions, and Santa Clara University’s James Kouzes and Barry Posner, begins to answer this question.

Kouzes and Posner created The Leadership Challenge, a model that they have refined over 35-plus years of research, using data from more than 1.3 million survey respondents. Their model organizes 30 leadership behaviors into five practices:

- Model the Way

- Inspire a Shared Vision

- Challenge the Process

- Enable Others to Act

- Encourage the Heart

Recently, Kouzes, Posner, and Calvert asked 530 B2B buyers which of the 30 leadership characteristics and behaviors the salespeople they currently do business with exhibited, and how frequently they exhibited these. The researchers also asked how often the buyers wanted to see these characteristics and behaviors. Buyers answered with ratings on a 1-to-5 scale. The data sets—which score both importance to buyers and frequency—are proprietary and unpublished, but Calvert shared some of the results with me.

Of the top 10 behaviors most exhibited by and desired from successful salespeople, eight fall into two categories: Enable Others to Act and Model the Way. Buyers said they would be more likely to meet with and buy from salespeople who more frequently exhibit these behaviors.

Five of the behaviors rated as most important to buyers fall into the practice of Enable Others to Act. Buyers wanted to work with salespeople who took the time to understand their needs, involved them in decisions, brainstormed with them, and brought new and useful information to the table. Successful entrepreneurs engage customers extensively in the value-creation process from the beginning. They even use the term “development partners” to describe their earliest customers. The buyers reported that their salespeople often exhibited these behaviors, as they scored an average of 3.85 out of 5 on the frequency scale.

Three of the behaviors most important to buyers fall into the Model the Way category, which involves showing commitment, fulfilling promises, and reliably adhering to agreed-on principles and standards. Entrepreneurs, who are often selling an incomplete version of their offering, succeed only by hitting critical short-term milestones, delivering promised value to customers on time in the early days. If they fail to meet and even exceed expectations early, their customers and investors lose faith, and that is the end of the nascent business. The salespeople working with the B2B buyers in Calvert’s sample exhibited these behaviors with an average frequency score of 3.89.

Salespeople exhibited the remaining 22 behaviors less frequently, with an average score of 3.37—lower than the average 3.87 on the top eight. But fortunately for salespeople, these behaviors were also required less often by buyers. Buyers wanted the top eight behaviors to be exhibited with a frequency of 4.24 out of five, versus 3.91 for the remaining 22.

Surprisingly for entrepreneurs, the behaviors in the Inspire a Shared Vision category, seemingly a critical requirement for entrepreneurs, came in dead last. The research implies that while inspiring a shared vision may be a top priority in engaging partners and employees and winning over investors, it is not the main reason that entrepreneurs are good salespeople. Calvert speculates that buyers are skeptical of a salesperson pitching a big vision and instead are more concerned with building a shared one and seeing reliable execution early on. Only then will buyers get excited about an overall vision.

Are entrepreneurs naturally great CEOs?

Kouzes, Posner, and Calvert connect frequently exhibited leadership behaviors to effective sales, and Butler demonstrates that entrepreneurs are natural salespeople. But are the characteristics that make people effective entrepreneurs and salespeople also useful to them if they become CEOs? Other research addresses this question.

Chicago Booth’s Steve Kaplan and Copenhagen Business School’s Morten Sørensen used an extensive data set, provided by management-assessment firm ghSmart, of more than 2,500 executive assessments—including those on more than 800 CEO candidates—to identify what characteristics and behaviors help CEOs land the top job, and succeed once they have it.

Kaplan and Sørensen discovered four factors that identify who is likely to both become a CEO and be successful in the job. The first factor is talent. Perhaps unsurprisingly, CEOs have higher overall ability than other executives, in that they scored well across the board on all the critical leadership traits ghSmart measures. The second factor emphasizes an execution orientation over strong interpersonal skills. Characteristics indicating a CEO’s ability to execute—such as speed of action taking, proactivity, and aggressiveness—correlated with success significantly more than interpersonal skills such as working well on a team, listening, showing respect, and being open to criticism. Kaplan says that often the most effective CEOs are not known for being “nice guys.”

The third factor CEOs manifest more than other executives is charisma, which Kaplan and Sørensen contrast with a strong analytical disposition. Successful CEO candidates showcase enthusiasm and persuasion over what the researchers term organization and analysis skills. The final factor involves where CEOs focus their time. They concentrate on the strategic big picture—leveraging vision, creativity, and smarts instead of the managerial talents of attention to detail, efficiency, organization, and accountability. (For more, see “Who gets into the C-suite?”)

While ghSmart’s evaluation criteria differ somewhat from CareerLeader’s assessment tools, there is substantial overlap: 70 percent of the skills evaluated by CareerLeader are the same as or similar to ones in ghSmart’s list. For instance, there is clear similarity between the skills that indicate Butler’s entrepreneurial traits of “thriving in uncertainty” and “strong persuasiveness” and Kaplan and Sørensen’s CEO factors of “strategic focus” and “execution orientation.”

Similarly, the behaviors of highly effective CEOs and successful entrepreneurs intersect as well. An article entitled “What Sets Successful CEOs Apart” in Harvard Business Review by four members of the ghSmart team augmented the analysis done by Kaplan and Sørensen to examine how the most successful CEOs act. They defined four related behaviors that set successful CEOs apart from less effective leaders, behaviors that entrepreneurs will recognize.

Deciding with speed and conviction even if the situation is ambiguous and the data are incomplete

When an entrepreneur is bringing a truly innovative product to market, she is always operating in an environment of imperfect information. Butler’s data suggest this is where entrepreneurs thrive.

Engaging for impact by developing a deep understanding of stakeholder needs and getting people onboard and aligned for action

As identified in Butler’s research, the entrepreneur’s passion for ownership and persuasiveness allows her to rally a variety of stakeholders around a vision in order to make it a reality. This behavior clearly matches with the Enable Others to Act category evidenced in Kouzes, Posner, and Calvert’s model.

Adapting proactively by keeping an eye on the future in order to react fast

ghSmart’s team finds that adaptable CEOs spend about 50 percent of their time thinking for the long run, while other executives devote on average 30 percent of their time to long-term thinking. Turning an idea into a large, successful company takes time and requires rapid response to changes in the market. Entrepreneurs rely on the technique of pivoting, popularized in Eric Ries’s 2011 book The Lean Startup, to keep their continuous adaptation headed in a positive direction, toward the long-term goal.

Delivering reliably by consistently following through on commitments

Reliability and follow-through are the key components of the Model the Way behavior, which buyers wanted to see more frequently from their salespeople in the Kouzes, Posner, and Calvert framework. Entrepreneurs who do not deliver are soon out of business.

It would seem that great entrepreneurs would naturally be strong CEOs, and yet most entrepreneurs will not run their companies as they grow over time. Yes, they possess crucial characteristics to lead, and this serves them well in launching new enterprises—and especially in engaging early customers. But Kaplan and Sørensen identified that talent was the No. 1 predictor of CEO hiring and success, and it’s one factor that entrepreneurs, especially young, first-time founders, need to develop over time.

The practical implications of all this

Research suggests that both the skill sets and behaviors of successful entrepreneurs, CEOs, and salespeople have significant overlap. Bringing these research sets together offers actionable insights for all three groups, as well as for investors betting on entrepreneurs and helping to hire the next generation of CEOs for their portfolio companies. To entrepreneurs, CEOs, salespeople, and investors, I offer some advice:

Entrepreneurs, I have written previously in CBR about the importance of learning to sell. (See “The elusive hockey-stick sales curve.”) Stop Selling and Start Leading, by Kouzes, Posner, and Calvert, and Daniel Pink’s important work To Sell Is Human both offer nontraditional approaches to sales that can help you engage customers more effectively and grow into the leadership role as your company scales, increasing your overall talent factor.

CEOs, with innovation and talent development high on every leader’s list, there is much to be learned from what entrepreneurs excel at. In a previous article (“Corporate leaders: Watch how entrepreneurs think”), I showcased what executives can learn from how expert entrepreneurs think, but Butler’s research and the work by Calvert’s team offer clues to how entrepreneurs act. In addition, Butler’s 2017 article “Hiring an Entrepreneurial Leader,” in Harvard Business Review, offers specific advice for how to recruit and interview for entrepreneurial talent in your pool of job applicants.

Salespeople, the lessons are obvious. Learn from how entrepreneurs interact with their earliest customers to build a joint value proposition. This behavior will improve the quality of your customer engagements. Adding leadership training to your personal development program will help you not only move into management, but improve your ability to hit quotas and begin to build your entrepreneurial tool kit.

Investors, consider Butler’s screening techniques to identify entrepreneurial talent when assessing investment candidates. Strong persuasion skills are a must for the selling required in the early days of a company’s launch. With both entrepreneurs and portfolio CEOs, prioritize execution over interpersonal skills. Coaching your companies’ leaders on the important characteristics identified by Kaplan and Sørensen may help these leaders push companies further along the path to a successful outcome.

Waverly Deutsch is clinical professor of entrepreneurship at Chicago Booth

- Timothy Butler, “Hiring an Entrepreneurial Leader,” Harvard Business Review, March–April 2017.

- Steve Kaplan and Morten Sørensen, “Are CEOs Different? Characteristics of Top Managers,” Working paper, September 2017.

- Jim Kouzes and Barry Posner, The Leadership Challenge: How to Make Extraordinary Things Happen in Organizations, 6th edition, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2017.

- Jim Kouzes, Barry Posner, and Deb Calvert, Stop Selling and Start Leading: How to Make Extraordinary Sales Happen, Hoboken: The Leadership Challenge, 2018.

- Elena Lytkina Botelho, Kim Rosenkoetter Powell, Stephen Kincaid, and Dina Wang, “What Sets Successful CEOs Apart,” Harvard Business Review, May–June 2017.

- Daniel Pink, To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth about Moving Others, New York: Riverhead Books, 2013.

- Eric Ries, The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses, New York: Crown Business, 2011.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.