How Much Should We Pay to Mitigate Climate Change?

- By

- September 02, 2014

- CBR - Public Policy

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns in its latest assessment that without dramatic intervention, the planet could warm by more than 4°C by 2100, and parts of the Earth could become uninhabitable on the hottest summer days. Economists and policymakers have yet to reach a consensus about how much we should pay now to avert this catastrophe, but research suggests we may want to pay hundreds of billions of dollars today to ward off trillions in future damages.

This conclusion can be drawn, with caveats, from a study about the long-run risk properties of housing. That’s because one crucial element of the climate-change calculation involves choosing a discount rate, which is an interest rate used to compare future and present values. When we consider a certain amount of money in the future, discount rates allow us to compute how much that amount is worth today. The smaller the discount rate, the higher the present value of the future money, and the more people are willing to pay today for future benefits.

In the case of climate change, suggested discount rates have varied widely. But Assistant Professor Stefano Giglio and coresearchers Matteo Maggiori of Harvard University and Johannes Stroebel of New York University’s Stern School of Business use housing data to provide the first direct estimates of discount rates for the very long run.

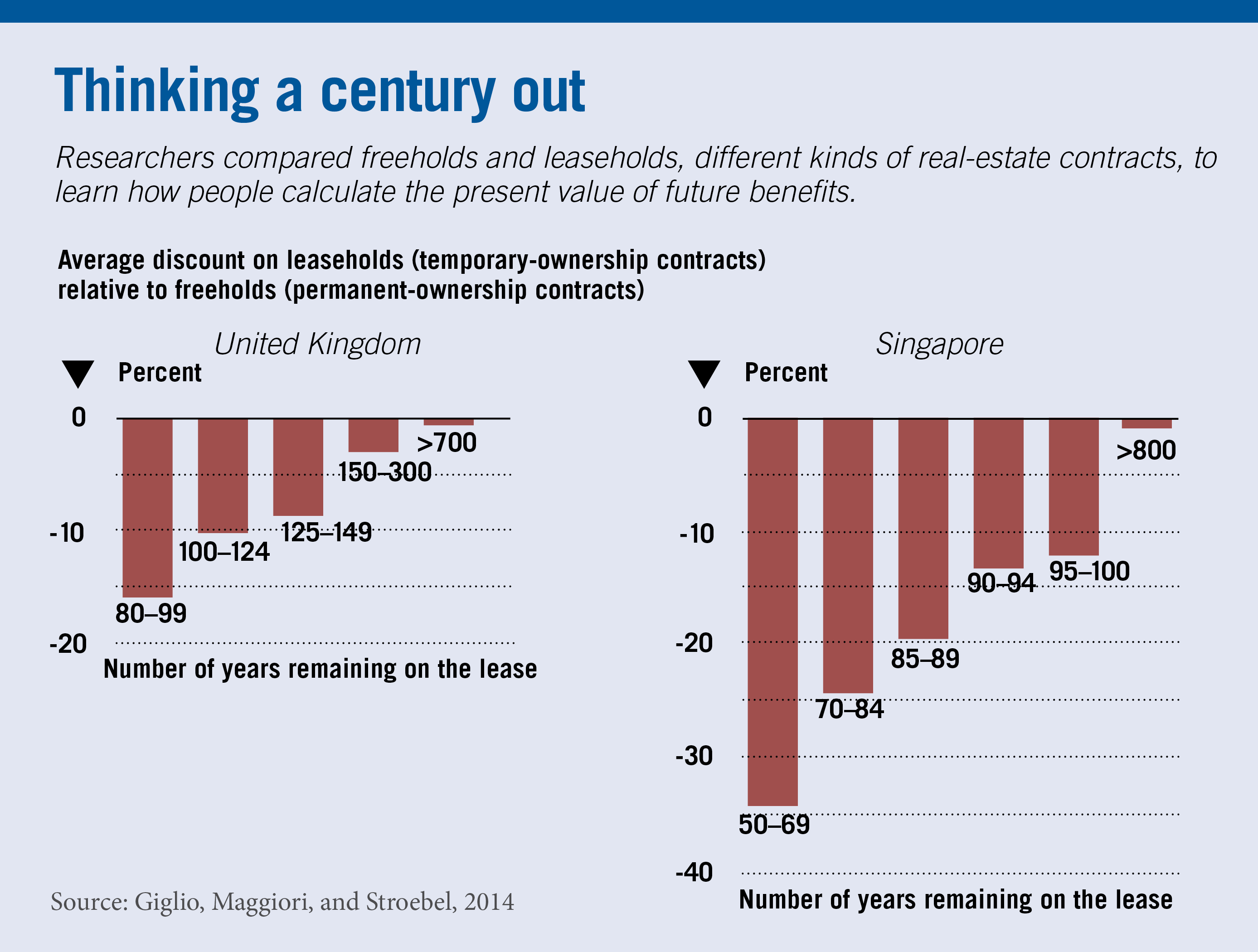

The researchers look at the United Kingdom and Singapore, where properties can be bought as freeholds (permanent ownership contracts) or as leaseholds (temporary prepaid ownership contracts with maturities between 50 and 999 years). Both leaseholds and freeholds can be bought and sold in the secondary market.

The researchers find that leaseholds with 100 years remaining are valued 10%–15% less than otherwise identical freeholds. For 125–150-year leaseholds, the price discount is about 5%–8%. For maturities of more than 700 years, leasehold discounts fall to zero. The fact that leaseholds with maturities longer than 100 years trade at substantially lower prices than similar freeholds indicates that individuals care about really long-term cash flows. The results suggest that households apply an annual discount rate of about 2.6% for benefits accruing beyond a century.

The authors note that households’ discount rates for payments very far in the future are “much lower than implied by most economic theory.”

Their discovery that very long-term discount rates are extremely low is significant for asset-pricing models and real-estate economics. But the results also suggest a reassessment of the value of climate policies, the authors say, because discount rates are an integral part of the discussion behind the benefits of such policies as reducing carbon emissions.

Imagine, as a writer did for the publication Grist, that carbon emissions are expected to cause $5 trillion in damages by the year 2100. Governments worldwide typically use a 5%–10% discount rate to determine their long-term environmental policies. At a discount rate of 5%, avoiding $5 trillion in damages by the end of the century would be worth $75 billion today.

The researchers suggest that the correct discount rate could be even lower, in which case people could be willing to pay much more than $75 billion. But Giglio also notes that the long-run risk properties of housing and climate abatement policies could be very different, so the appropriate discount rate for environmental policies may vary from the one found in the housing study.

Stefano Giglio, Matteo Maggiori, and Johannes Stroebel, “Very Long-Run Discount Rates,” NBER working paper, March 2013.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.