Researchers look at the evidence in Norway nearly a decade after a quota on female board members became law.

- By

- June 15, 2015

- CBR - Economics

Researchers look at the evidence in Norway nearly a decade after a quota on female board members became law.

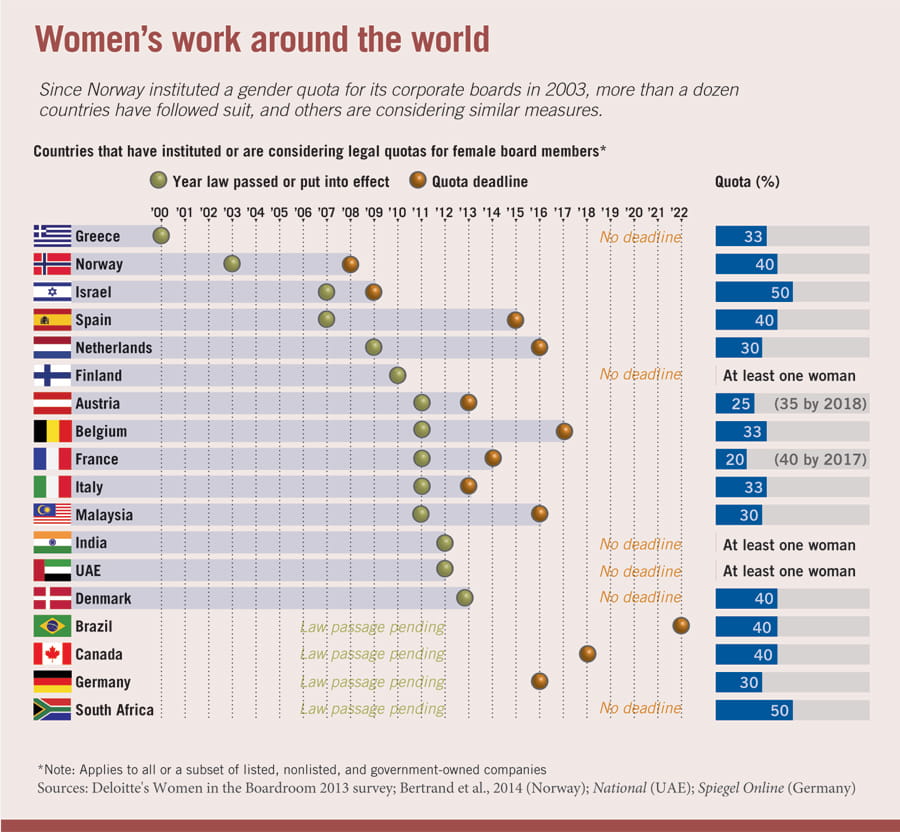

When Norway instituted a 2003 quota that 40 percent of corporate board members must be female, proponents hoped the measure would also pay off for women in the lower ranks. Even before seeing concrete results, more than a dozen other countries—from Sweden to Malaysia—quickly implemented similar quotas. Many of these countries had boards with an average of fewer than 10 percent women.

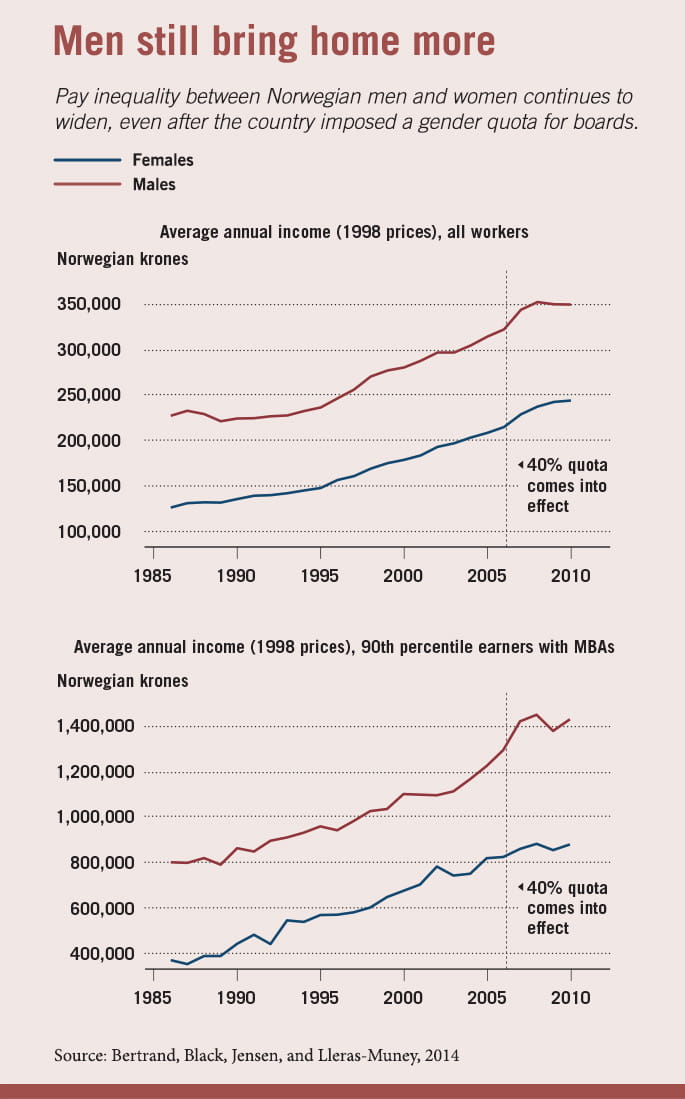

Such mandates could have mixed results, according to Marianne Bertrand, Chris P. Dialynas Distinguished Service Professor of Economics at Chicago Booth, who looked at Norway nearly a decade after the quota became law. In a study coauthored with Sandra Black of the University of Texas, Sissel Jensen of the Norwegian School of Economics, and Adriana Lleras-Muney of the University of California, Los Angeles, she finds that female directors have benefited from the law, but those improvements haven’t translated into higher average earnings for women broadly, or a markedly increased likelihood of a woman joining the C-suite.

The authors also find evidence contradicting the claims of Norwegian companies that the law would make it more difficult to find qualified female candidates. Thanks to the quota, companies have closed the pay gap between female and male board members, and they are recruiting more qualified female executives to their boards. “The reform spurred a more widespread search effort and helped break some of the ‘old boys’ networks that may have dominated the board appointment process prior to the reform,” the researchers write.

Norway has long had a progressive view of addressing the gender gap and is known for its generous family leave policies for women and men. It’s ranked second out of 136 countries in terms of opportunities for women, according to the 2014 World Economic Forum Global Gender Gap Report. The country is also not new to quotas. It has had regulations in place to address gender diversity in government-appointed boards since 1981.

Despite gender-balance successes in areas of the home such as childrearing, the country has seen little change in businesses promoting more women to top spots. In Norway, only 8 percent of board chairs are women, while females make up 4 percent of chief executives and 12 percent of chief financial officers, according to research from public-relations firm Burson-Marsteller about companies listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange. And while the quota passed in 2003, officials were compelled to add sanctions five years later, which meant a company could be dissolved for noncompliance. The threat of sanctions helped move the number of women on boards from 17 percent in 2005 to 40 percent in 2008.

The researchers collected data about male and female board members from 1998 to 2010, seven years after the legislation passed. They recorded earnings of male and female board members prequota and postquota to show that salaries are converging and that as women’s incomes rise, the incomes of male board members stay unchanged. In addition to online surveys, the researchers used Statistics Norway registry data and the Register of Business Enterprises to get information on specific individuals.

For Benedicte Schilbred Fasmer, chair of the Oslo Stock Exchange, the idea of quotas felt wrong in the beginning. “I was really against quotas to start with, for the pure reason you really hope that as a competent individual you are selected for what you can contribute with rather than being someone with a certain characteristic,” she says. Fasmer, who is 49, holds an executive management position at financial-services group DNB and was previously a board member at Norwegian Air Shuttle and the Argentum Centre for Private Equity at the Norwegian School of Economics.

Now that the law is fully implemented, she has seen more executives become interested in increasing diversity. Some companies “really want to have a more equal representation of women in senior management, but don’t have a good recipe yet of how to achieve it,” she says.

France, Iceland, and Italy have all implemented quotas similar to Norway’s since 2003. India and Malaysia have introduced legislation to help gender parity in the workplace, and the United Arab Emirates is considering ideas to improve opportunities for professional women, says Dan Konigsburg, managing director at Deloitte’s Global Center for Corporate Governance. “There can be few subjects of corporate governance and public policy that have expanded so far over such a small period of time,” the Deloitte researchers write in the company’s 2013 Women in the Boardroom report. At least 13 countries have adopted similar policies to Norway’s, and four more are considering quotas or have similar regulations.

“Norway has been that spark that’s really encouraged other countries to climb aboard,” says Konigsburg, who is based in New York.

Konigsburg does not expect boardroom quotas to reach the United States soon. However, he says there are signs that in the US and the United Kingdom, change may come due to bottom-up pressure from activists rather than top-down mandates. “Shareholders are grabbing hold of this and making their voices heard,”

he says.

Malli Gero, president of 2020 Women on Boards, a Boston nonprofit that aims to have women occupying 20 percent of US board spots by 2020, agrees that US quotas are unlikely. That said, there are other efforts to increase diversity in the boardroom, she says. US “companies are getting the message, and many are adding women to their boards without regulation.” Women hold more than 17 percent of board seats in the Fortune 500 companies, a number that’s remained constant over the past six years, according to Catalyst, a firm that studies women in business. The process of achieving gender parity is slow, as US board seats become available once every two years, on average, and have no term limits.

At the time that the boardroom regulation was implemented in Norway, more businesses were going private, limiting the quota’s reach, since private companies are exempt. (A separate regulation passed at the same time allowed financial firms to become privately held.) Out of 564 Norwegian businesses that were listed in 2003, only 179 remained public limited-liability companies five years later.

For those companies that complied, the board election process procured better-trained professionals. Following the reform, female board members had completed an average of six months more education compared to their prequota counterparts. In addition, the gender gap in board members with a business degree or MBA nearly disappeared. These findings suggest “that previously untapped networks of top business women were activated by the policy,” Bertrand and her co-researchers write.

Judging from her own experience, Schilbred Fasmer agrees, saying that recruiting for board positions now includes more evaluation of credentials, rather than a narrow focus on personal connections. “You have much more formal evaluation of the board member and his or her competence levels,” she says. “[Companies] are recruiting new board members much more professionally now.”

There are few concrete changes for Norwegian women starting their business careers, and there still seems to be limited interest in grooming future female executives. Nevertheless, the research indicates that younger women are hopeful for gender parity in the workplace. Surveying 763 business-school students at the Norwegian School of Economics, the authors find that 50 percent of the female participants expect their earnings to increase due to the law, while 30 percent of male participants expect their earnings to decrease because of it. “It is telling that young women preparing themselves for a career in business widely support the policy and perceive it as opening more doors and opportunities for their future career,” the researchers write.

The researchers say a 10-year-old regulation is not old enough to fully evaluate its results. “You have to hope that this will eventually trickle down to having more women in quality positions,” says Bertrand.

For now, the researchers note that boards have only slight influence on the day-to-day of a corporation. “Boards may have little say in recruiting decisions or human resource policies,” the researchers write.

At the same time, Bertrand says quotas should be viewed as a way to inspire systemic change through all levels of management, rather than as a quick fix to patch up gender imbalances. “Part of the danger with this kind of policy is that if you have a policy that addresses the glass ceiling, you can forget the gender issue and assume the problem away,” she says.

Others point to the “golden skirts” argument, which claims that the same exclusive club of female board members is filling all of the available seats in Norway. While there’s little research supporting or refuting these assertions, there’s some anecdotal evidence that the same women serve on a greater number of boards, says Deloitte’s Konigsburg. And, he says, “You are much less effective when you’re on 10 boards—there are limits to what you can do.” Proponents of the quotas say this is a temporary problem and that the pool of women available to serve on boards is slowly widening.

Schilbred Fasmer, who speaks at business schools about the importance of women in finance, says companies should focus on mentoring opportunities and accommodations for working mothers. Board quotas have made it easier for companies to have open conversations about the number of women in executive and senior management roles, she says, but companies need to recognize that quotas alone cannot increase diversity at the top. “You don’t change the management just because you change the board,” she says.

Female leaders in Norway say the quota has stirred a conversation about women in upper management at companies such as Storebrand, a Norwegian savings and insurance company headquartered near Oslo. After a recent push from the chief executive, the company has women in three of eight executive roles and has implemented a program to develop female managers. The strong approach to mandating gender balance was difficult to process at first, but it’s paying off beyond the boardroom, says Storebrand’s director of corporate communications, Elin Myrmel-Johansen. “Gender [parity] is about strengthening business, not about being nice,” she says.

Marianne Bertrand, Sandra E. Black, Sissel Jensen, and Adriana Lleras-Muney, “Breaking the Glass Ceiling? The Effect of Board Quotas on Female Labor Market Outcomes in Norway,” NBER working paper, June 2014.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.