Newborns with virtually no visual experience prefer to look at faces over equally complex objects. Primate brains contain neurons, usually concentrated in a few regions in the inferior temporal cortex, that selectively respond to faces. Our brains are specialized to process faces. We are face experts.

From the moment we are born, we are exposed to faces. We see thousands of them over our lifetime, and we can detect subtle differences in them. We can discriminate between any two faces, and we form impressions from extremely little information.

Try this: fixate on the circle below, and a face will appear very briefly, for around 50 to 100 milliseconds.

What did you see, a man or a woman?

We are efficient at forming impressions from faces. Typically an exposure of about 100 milliseconds is all that is needed for someone to read demographic attributes such as race and age, emotional states, cognitive states such as effort and exhaustion, focus of attention, and eye gaze. One hundred milliseconds is the time it takes the information to get from your retina to the parts of your brain that process faces—but within half a second, you are basically done forming an impression.

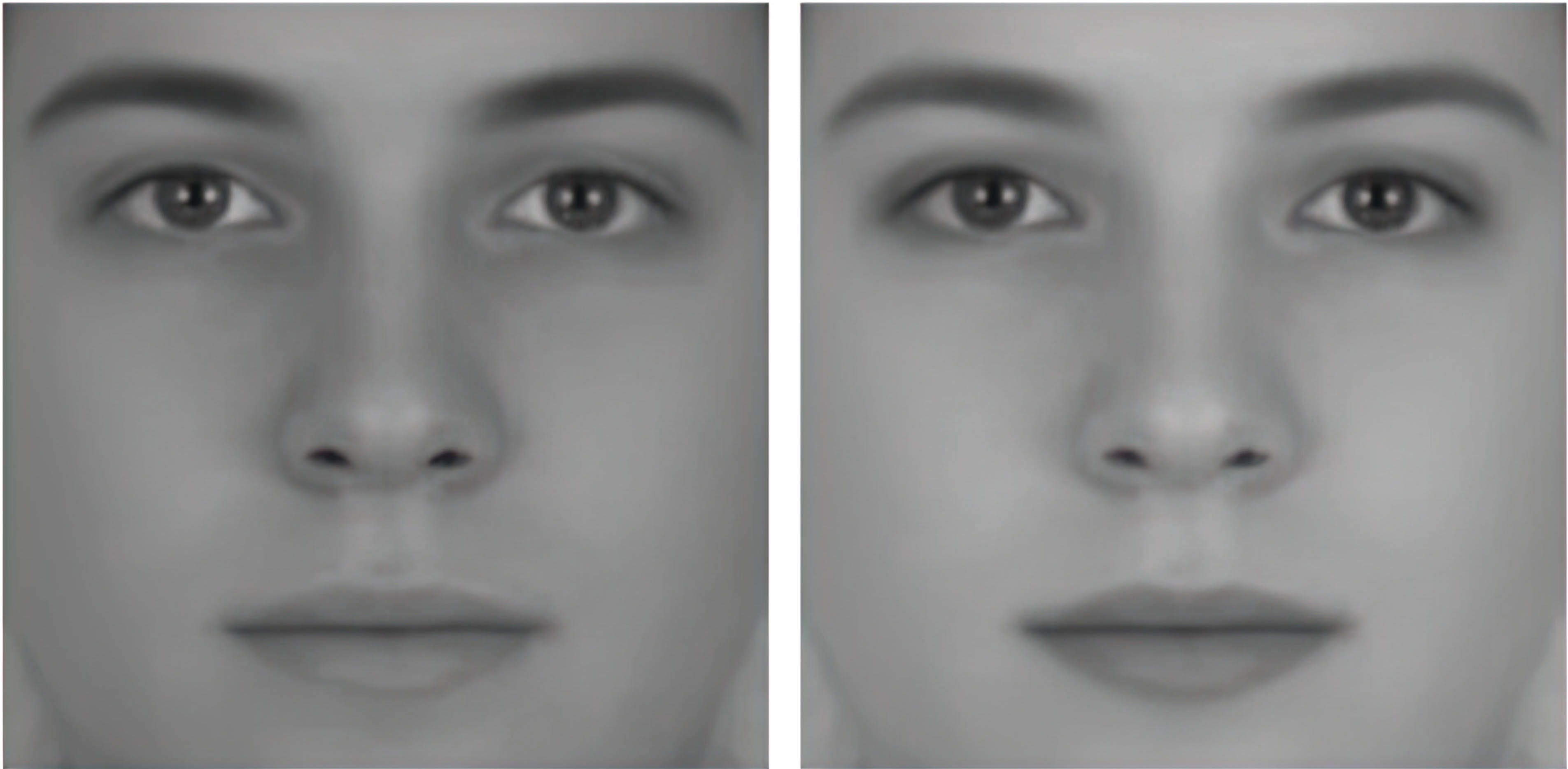

© Richard Russell

A face can reveal information, such as gender. These are two identical faces in every respect, except that the skin on one is a little bit darker. If I ask you to identify the male face, you will likely say that it’s the darker one. That’s often correct. In every culture in which researchers have measured people of the same ethnicity, men have tended to be darker than women. This seems to be a stable, biological difference.

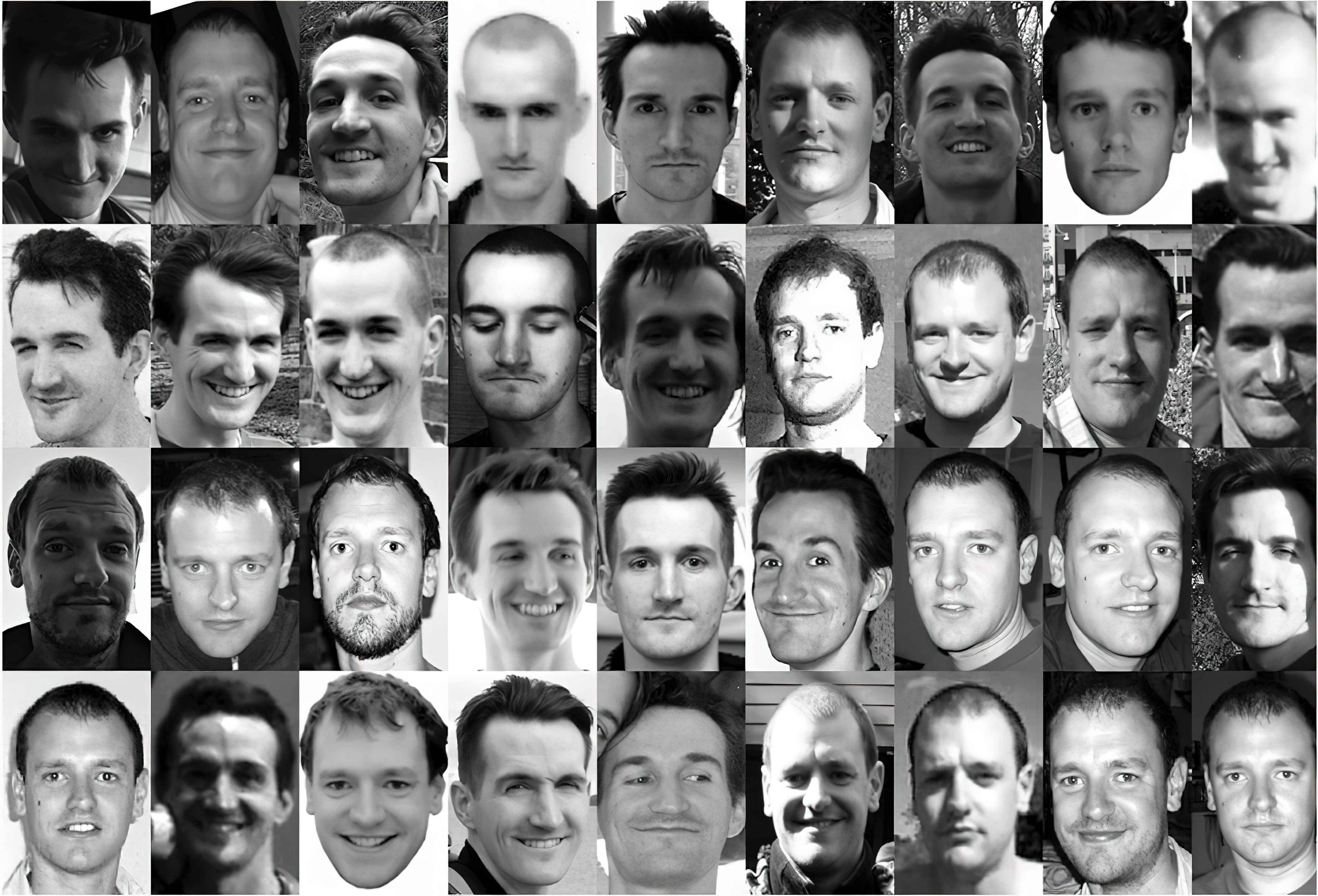

Images courtesy of BMJ

Information from the face can also reveal information about someone’s underlying health. This image comes from a large study, led by University of Southern Denmark’s Kaare Christensen, that tracked sets of twins over time to see how long they would live. Biological age was the best predictor of how long someone would live, but it turns out that the next best predictor was how the participants looked relative to their biological age. Those whose faces looked younger actually lived longer.

At first that seems quite amazing, but it’s less surprising when you start digging into the data. What makes us look younger? Well, when we’re aging, our face is aging too. Some people benefit from good genetics or wealth and better access to health care. On the flip side, we are affected by things that make us look older, conditions such as asthma, chronic sun exposure (not from vacationing but from working outside), and smoking. These accumulated advantages and disadvantages are imprinted on our bodies and faces.

But people can also use information inferred from a face in problematic ways. After a brief exposure to a face, people make all sorts of assumptions about a person’s presumably stable personality attributes—about whether the person is trustworthy, competent, or aggressive, for example.

These kinds of inferences have been a point of fascination throughout history, and they highlight what I call the physiognomist’s promise. Physiognomy is the pseudoscience of reading character from faces, and the main promise is that you can infer people’s personalities from their facial features.

The practice goes back to ancient Greece but really picked up in the 18th century, when Johann Caspar Lavater, who was a clergyman in Zurich as well as an influential and prolific writer, wrote four volumes of essays on physiognomy.

Because of the influence of Lavater’s ideas, Charles Darwin, on account of his nose, was almost denied the chance to take his historic HMS Beagle voyage. The captain of the Beagle happened to be a fan of Lavater’s, and he didn’t believe that a person with such a nose would possess sufficient energy and determination for the voyage. Luckily for science, Darwin made it and later wrote in his autobiography, “But I think he was afterwards well satisfied that my nose had spoken falsely.”

Noses, for some reason, were popular to analyze in the 18th and 19th centuries. There was a whole branch of physiognomy called nosology, with entire books dedicated to reading the character of people from their noses. Physiognomists’ notions are funny and ridiculous, except that their promise is alive and well—primarily because we are all naïve physiognomists, forming instantaneous impressions from faces and acting on them.

Physiognomy in the modern world

Imagine that you’re walking into a party and these are the first two people you see:

These faces, which were generated by a mathematical model that visualizes our impressions of different traits, illustrate our impressions of extraversion and introversion. The prototypical extroverted face is on the left, and the prototypical introverted face is on the right. If you’re going to a party and your objective is to have fun, you would likely approach the extroverted-looking person. Most participants, when asked, said that’s whom they would approach.

Who would make a better CEO? These faces illustrate our impressions of competence, and these impressions influence our decisions. If you’re trying to pick the person who would make a better CEO, you will pick the person you think is more competent.

Images from the Basel Face Database, courtesy of M. Walker

If you’re hiring a security guard, you’ll probably pick the person whose face looks more masculine.

If hiring a babysitter, you would hire the person who seems more trustworthy.

These impressions from faces are immediate and compelling. You don’t stop to think—you form an immediate impression and make an instantaneous decision about the character of the person. And your impression and the resulting decisions can be consequential.

My coauthors and I showed study participants pairs of images of US political candidates, removing any pictures of familiar, famous people. Just using participants’ first impressions, we were able to predict election outcomes with about 70 percent accuracy, and the results have been replicated in many other countries using photos of local politicians.

University of California at Berkeley’s Gabriel S. Lenz and MIT’s Chappell Lawson, both political scientists, have followed up on this work, so we know that the effect is driven by people with little political knowledge who watch TV. They’re substituting a complex question (how competent is each candidate?) with an easy one (how competent does each candidate look?). In a sense, they’re looking for the right information in the wrong place, because it is expedient.

These impressions influence voting decisions, and many other decisions as well. As I discuss in Face Value: The Irresistible Influence of First Impressions, research has demonstrated that competent-looking CEOs are not necessarily better at their jobs, but they’re more likely to get high compensation packages. Dominant-looking cadets are more likely to achieve higher military ranks. And trustworthy-looking borrowers are more likely to get loans, and to get them with a lower interest rate.

Worryingly, there are technological startups promising to profile personalities on the sole basis of facial images. There are scientific publications claiming that algorithms can read criminal inclination, sexual orientation, political orientation, and more from facial images alone. Physiognomy has never gone away; it’s just wearing new clothes.

Discounted because of appearance

I see two reasons for why physiognomy is so appealing. First, it promises an easy solution to a complex problem, which is how to figure out the intentions and capabilities of strangers. For most of human history, people lived in extended families with rich firsthand and secondhand information about others. The emergence of modern states changed all this, and we had to learn how to live with strangers without trying to kill them or being afraid of being killed.

Most people we meet now are, thankfully, not out to kill us—but we’re still trying to figure out their intentions and capabilities. Consider an employer trying to evaluate prospective candidates for a job. In the early 20th century, the married writers Katherine M. H. Blackford and Arthur Newcomb published several influential books espousing “character analysis,” with arguments based not on Lavater’s flimsy logic but on what they understood as “evolutionary” theory. When trying to find the right person for a job, Blackford and Newcomb essentially said, just look at the candidate and do a character analysis on the basis of appearance. What the candidate said didn’t matter in their view. Letters of recommendations were worthless.

The reality is that Blackford and Newcomb were wrong. Letters of recommendation are actually more predictive than unstructured interviews. As for the idea that you learn something by analyzing a candidate at a meeting, this is called the “interview illusion.”

But appearance sways employers, even in domains such as sports with lots of evidence about the capabilities of others. The book Moneyball by Michael Lewis is about the unlikely success of Billy Beane, the general manager of the Major League Baseball team the Oakland Athletics, whose success was due to his exploiting the prejudices of appearance. He worked with much smaller revenues than other teams, yet the A’s were consistently one of the best clubhouses because he found players who were undervalued because they didn’t look the part.

Billy Beane was looking for “those guys who for their whole career had seen their accomplishments understood with an asterisk,” Lewis wrote. “The footnote at the bottom of the page said, ‘He’ll never go anywhere because he doesn’t look like a big league ball player.’ . . . Young men who failed the first test of looking good in uniform.’” Beane recognized that inferences we make from appearances are often wrong, and he used that to build a winning team, relying on statistical information based on past performance.

Making stereotypes visual

The second reason the physiognomist’s promise is so appealing is because it agrees with our intuitions. We form impressions quickly, and our impressions often seem to be shared by the people we know.

The faces you saw above were generated by computational models, which visualize our facial stereotypes. To build these models, we start with a statistical representation of faces: each face is a set of numbers. We can randomly generate thousands of faces, then ask people to rate them on perceived attractiveness, trustworthiness, or anything else of interest. In this way, we can build a computational model that captures the variations in facial appearance that lead to changes in ratings. Then, we can generate new faces (including hyperrealistic ones) and manipulate those on the basis of these models. When we show these faces to new study participants, the judgments people make match the model’s predictions.

But the faces that our models spit out do not capture personality characteristics, and this is the essential difference between the work that we do and the physiognomists’ work. The models capture systematic biases in judgments. They visualize our stereotypes or those of a particular group—in our case, mostly white American study participants. The physiognomists’ promise confuses the impression (your cognitive and emotional response) with the real thing.

The promise also assumes that faces are the same as images of those faces, when in fact images are an imperfect, variable representation. There are pictures of yourself that you like more than others, after all. Great photographers are employed precisely because they have the ability to make us look better than we usually do.

It’s not immediately obvious that image variation, even if it’s random, can generate completely different impressions of the same person. How many individuals are shown below?

Reproduced by permission of Elsevier

The typical guess is five. The answer is two. This question is difficult because you don’t know the people in the photos. Recognition brings with it knowledge. When you don’t recognize or know anything about a person, facial images provide little information and likely unlock stereotypes. Different images of the same unfamiliar person can lead to dramatically different impressions.

The physiognomist’s promise underestimates the huge effect of image variation on impressions and the influence of momentary mental states. A study done in Sweden showed participants pictures—real ones, not generated—of the same people when they were rested and when they were sleep deprived. Participants rated the images of sleep-deprived people as less attractive and less intelligent. Note that the inference of intelligence is warranted in the immediate situation: when we are sleep deprived, we are incapable of doing many “smart” things such as driving safely or solving complex problems. But to draw a larger conclusion about someone’s intelligence is an inferential leap.

First impressions are constructed from cues that have some significance in the immediate situation. They’re grounded in momentary emotional and cognitive states such as happiness and exhaustion and in stereotypes such as masculinity, femininity, and age—from which we make overgeneralizations. Leslie Zebrowitz of Brandeis University has a lot of work demonstrating that people make all kinds of inferences about “baby-faced” adults. As one example, they’re perceived as naive and not physically tough. Meanwhile, individuals with feminine faces are perceived as more trustworthy. Individuals with masculine faces are perceived as more competent, and so on.

Using our models, we can actually identify the role of specific stereotypes in impressions. Consider what’s behind perceived competence. National University of Singapore’s DongWon Oh, Princeton’s Elinor Buck, and I identified three components of competence impressions, one of which is attractiveness, which benefits women. But when we controlled for attractiveness, what was left was mostly masculinity—which people were using to assess competence. Even worse, we can inject masculinity into photos of real faces, and when we made a face more masculine, it was perceived as more competent. But when we did this for a female face, gender stereotypes changed the result. The stereotype goes against dominant-looking masculine women. Although masculinity is a characteristic associated with leaders, if you put too much in a woman’s face, it prompts a negative response. By visualizing our facial stereotypes, we can identify pernicious biases that can lead to unfair and suboptimal decisions. (For more on this research, see “How first impressions work against women.”)

Do not be misled by surface irregularities

Often, the things we rapidly infer from faces, such as age, gender, and emotional states—and the personality impressions we construct from these first-order inferences—can be inaccurate, overestimating the role of the face.

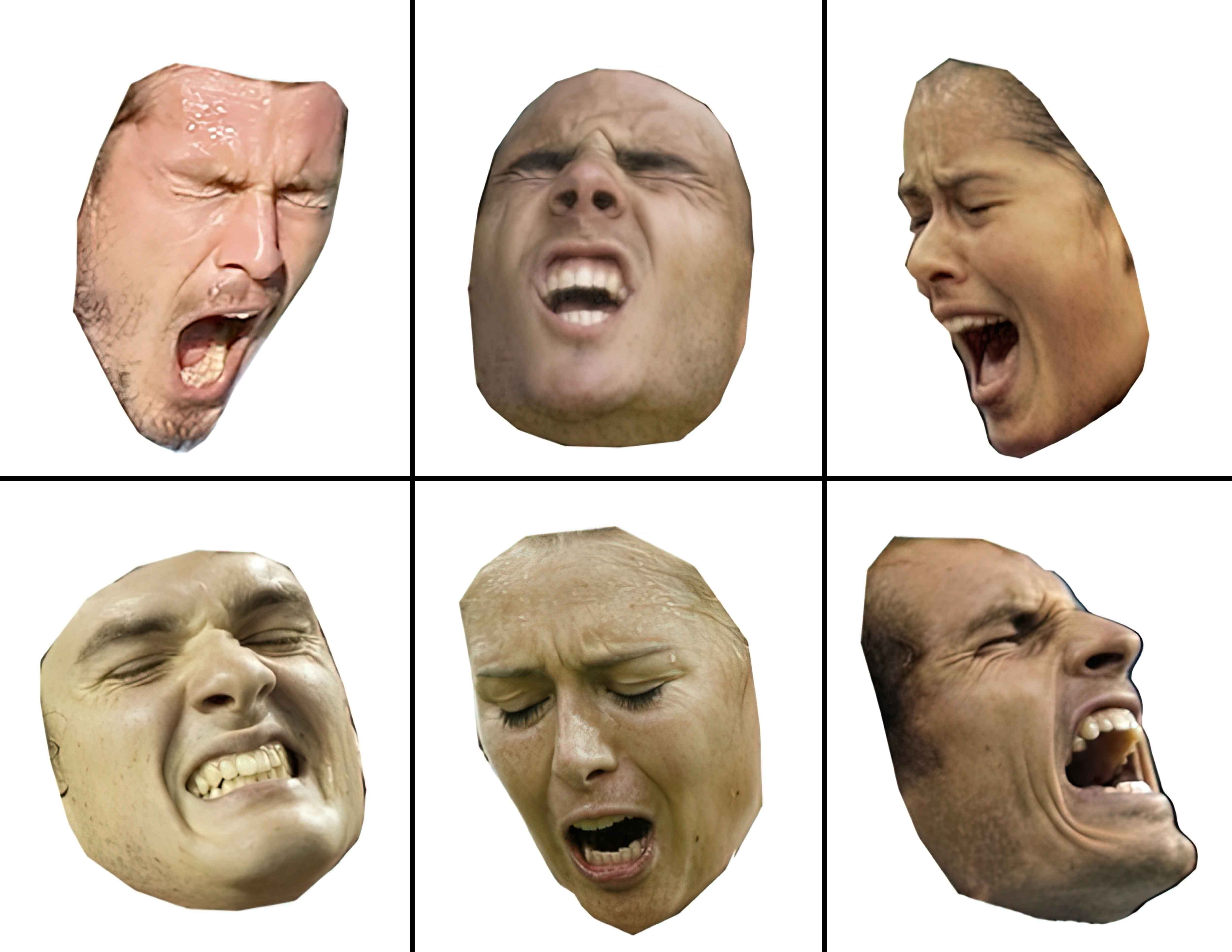

Reproduced by permission of AAAS

These are photos of tennis players after they won or lost a point, but the faces themselves don’t give you any information about who won or lost. The photos show dramatic reactions, but you don’t know what the direction of the emotion is. If we just show the body, that does the trick, so we know the answer is not in the face.

First impressions function as a shortcut for dealing with the complexity of living with strangers. Some of these impressions might be accurate in the here and now. A disgruntled-looking person is probably not going to help you, for example, while someone happier looking might be more likely to. But first impressions are inaccurate as a guide about personality characteristics that are stable over time and situations.

Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, probably one of the most interesting and least known 18th-century thinkers—he was the first chair of experimental physics in Germany, posthumously credited with introducing the aphorism into the German language—was skeptical and critical of Lavater’s ideas. He too was fascinated with and enjoyed interpreting faces, but he recognized, among other things, that physiognomy could be used to justify prejudice and that there was a limit to what someone’s appearance revealed about their inner selves. As he put it, “First impressions lend the smallest possible knowledge the greatest possible appearance of it. Consider someone wise who acts wisely, and do not be misled by irregularities on the surface.”

Alexander Todorov is the Leon Carroll Marshall Professor of Behavioral Science and a Richard Rosett Faculty Fellow at Chicago Booth. This essay is adapted from a talk given in March at a Think Better event sponsored by Booth’s Center for Decision Research.

- John Axelsson, Tina Sundelin, Michael Ingre, Eus J. W. van Someren, Andreas Olsson, and Mats Lekander, “Beauty Sleep: Experimental Study on the Perceived Health and Attractiveness of Sleep Deprived People,” BMJ, December 2010.

- Kaare Christensen, Mikael Thinggaard, Matt McGue, Helle Rexbye, Jacob von Bornemann Hjelmborg, Abraham Aviv, David Gunn, Frans van der Ouderaa, and James W. Vaupel, “Perceived Age as Clinically Useful Biomarker of Ageing: Cohort Study,” BMJ, December 2009.

- Gabriel S. Lenz and Chappell Lawson, “Looking the Part: Television Leads Less Informed Citizens to Vote Based on Candidates’ Appearance,” American Journal of Political Science, April 2011.

- DongWon Oh, Elinor Buck, and Alexander Todorov, “Revealing Hidden Gender Biases in Competence Impressions of Faces,” Psychological Science, December 2018.

- Joshua C. Peterson, Stefan Uddenberg, Thomas L. Griffiths, Alexander Todorov, and Jordan W. Suchow, “Deep Models of Superficial Face Judgments,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, April 2022.

- Alexander Todorov, Face Value: The Irresistible Influence of First Impressions, Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.