Master Class: Startup Basics

Chicago Booth's Waverly Deutsch offers four key lessons to entrepreneurs.

Master Class: Startup BasicsRecently I received an email request from an entrepreneur to help figure out how to drive traffic to his fast-casual Indian restaurant without spending a boatload on marketing. The establishment had received favorable reviews by critics in local papers and by patrons on Yelp. He had drawn his own conclusion that his fundamental problem was the restaurant’s location. I gave him some blunt feedback:

One of the hardest problems to solve in the retail space is picking the wrong location. There are so many restaurants people can choose from that it is hard to become a destination that people will make the effort to go out of their way to try. It does happen. Think Urban Belly in Logan Square [a Chicago neighborhood]—somehow it went viral and became the hot spot for a while. But it is rare, and the cuisine has to be unique in some way. All the marketing in the world won’t make people go out of their way for good Indian fast-casual. There is just too much competition. Because restaurants have low barriers to entry and are not too expensive to start, there are way more restaurants that start up than the economy can absorb, so they do tend to fail at a pretty high rate.

Most people have heard the conventional wisdom that says restaurants are risky ventures, and only one in 10 survives. Anecdotes would seem to confirm this, as you may have noticed eating establishments come and go in your favorite neighborhood. It makes you wonder why anyone would risk so much to start something so likely to fail.

But like so much common wisdom in entrepreneurship, this failure rate is a myth. In doing additional research, prompted by the restaurateur’s email, I found that new-restaurant failure rates are far different than most people think. In fact, it’s dicey to make general statements about the survival or failure rate in any particular industry.

Scott Shane, in his excellent book The Illusions of Entrepreneurship: The Costly Myths That Entrepreneurs, Investors and Policy Makers Live By, examined US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data to identify new-business failure rates by industry. He looked at companies started in 2005 and determined that industry does matter in terms of the statistical chances that a new business will survive for five years. However, survival rates ranged from 36 percent to 51 percent across industries as varied as mining, services, retailing, and construction. No industry—including food services—showed a 90 percent failure rate.

In reviewing these data, I was surprised to see that retail and services—sectors with low barriers to entry and relatively low start-up costs—fared better in terms of survival rates than industries more difficult to break into, including finance, transportation, and construction. I decided to update Shane’s numbers to verify this counterintuitive observation.

The companies Shane looked at started in 2005 and had to endure the worst recession in US history since the Great Depression. But what about companies that started after that economic disaster? Using the BLS Business Employment Dynamics data, I discovered that companies that started in 2011 were in industries that had overall higher survival rates than those Shane looked at, with rates ranging from 45 percent for firms in the mining sector to a whopping 66 percent for agricultural start-ups.

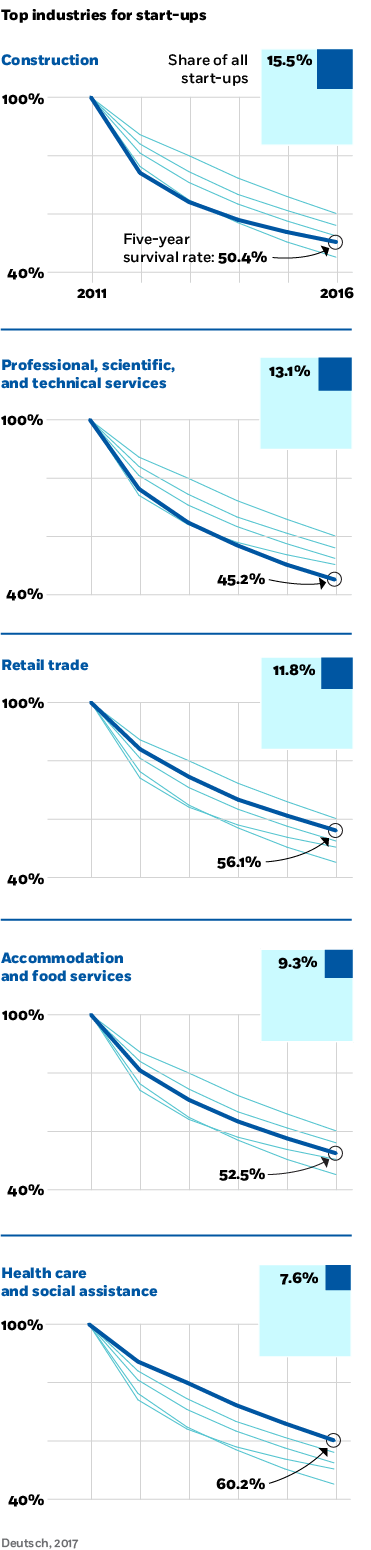

Not only were overall survival rates higher, they changed over time—and survival rates for individual industries rose and fell relative to those of others. Mining moved from the industry with the highest survival rates in 2005 (51 percent) to the lowest in 2011 (45 percent). The construction industry bounced back from a 36 percent survival rate in 2005—during a real-estate and market crash that was caused largely by the mortgage and banking crisis, and that so clearly had an impact on the building trades—to 50 percent in 2011. Retail also had a huge surge, from 41 percent to 56 percent—giving retail businesses that started in 2011 a 15 percentage point greater chance of survival.

A good year for start-ups

Companies that entered the market in 2011—following a period of years that saw more start-up failures than successes—fared well across many industry sectors.

Why was 2011 such a great year to launch a new company? According to the US Census Bureau’s Business Dynamics Statistics, from 1977 to 2008 the US economy saw a net addition of companies every year—as more new ones formed than went out of business. But in the three-year span from 2009 to 2011, company deaths exceeded births each year, and the economy lost a total of 211,496 companies.

This seems to have left a gap in the market, so entrepreneurs starting their companies from 2009 to 2011 had nearly a 51 percent chance that their firms would still be in business five years later—almost 3 percent higher than the survival average for the previous decade and a half. The only other stretch during that period when survival rates hit 50 percent was in 2002 and 2003, right after the tech crash. So it would seem that right after a market downturn is a good time for entrepreneurs to start new ventures.

But these numbers reflect average survival rates across broad industry sectors. How many entrepreneurs are really starting mining, agriculture, or manufacturing businesses? Those are not exactly the hot sectors that people read about in the press, yet they have more entrepreneurs than one might expect. In 2011, there were more than 20,000 new companies launched in these areas, giving us a large data set to consider. These giant industries collectively contribute 16 percent to the overall US GDP, so there would seem to be a lot of room for new entrants. But they are unpopular for entrepreneurs, accounting for only 4 percent of start-ups.

What is going on with the most popular sectors for new start-ups? The top 10 industries, accounting for 86 percent of all new companies in 2011, saw five-year survival rates ranging from 45 percent in the professional, technical, and scientific-services sector to 60 percent in health care and social assistance. I find no correlation between survival rates and the size of the overall market as measured by percent contribution to US GDP. Apparently the economy can absorb new companies in growing markets such as health care as well as shrinking sectors such as retail and construction.

What does all this mean for entrepreneurs? Timing in the broader economy and a good value proposition mean more than what industry you choose. A cold industry—be it construction or agriculture—might get hot. Highly competitive markets such as restaurants and retail are just as likely to produce successful new companies as sexier industries such as high tech and finance.

Statistics don’t mean much to most entrepreneurs, including the intrepid restaurateur trying to drive traffic to his fast-casual Indian restaurant. Restaurant failure rates may not be 90 percent, but even 50 percent is a high hurdle. He responded to my feedback by saying,

I appreciate your honesty and value your views. I do understand the competition in this market as well as the high failure rates but at this juncture I am all in and all I can do is work my hardest and give it my best so that no matter what the outcome, on hindsight I won’t say I could have done more.

For entrepreneurs, passion outweighs statistical odds. Even when facing the uphill battles of a bad location and a tough market, this entrepreneur needs to give it his all, so that he will have no regrets—succeed or fail. That resilience characterizes all successful entrepreneurs. And to them I say, keep fighting the good fight.

Waverly Deutsch is clinical professor of entrepreneurship at Chicago Booth.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.