We live in an age of growing corporate inequality, with a few dominant companies and many underperformers.

The superstar archetype is Google, established in 1998 with the aim of rank-ordering web pages in what was then the nascent industry of search. By the beginning of the 21st century, Google had no revenues and no established business model. Fast-forward 18 years and a few hundred acquisitions, and Alphabet, Google’s parent company, has a market value in excess of US$750 billion.

In almost every industry, a small number of companies are capturing the lion’s share of profits. The top 10 percent of companies worldwide with more than $1 billion in revenues (when ranked by profit) earned 80 percent of all economic profits from 2014 to 2016, according to a recent study by the McKinsey Global Institute. The 40 biggest companies in the Fortune 500 captured 52 percent of the total profit earned by all the corporations on that list, according to an analysis of the 2019 ranking by Fortune.

This leaves less and less for the smaller fish to feed on. The middle 60 percent of businesses earned close to zero economic profit from 2014 to 2016, according to McKinsey, while each of those in the bottom 10 percent recorded economic losses of $1.5 billion on average.

Why do some companies succeed so categorically while the majority struggle? This question drives much of the management-consulting industry. It has also inspired a library’s worth of management books with varying explanations. Is it because successful companies have visionary and disciplined leaders, as management consultant Jim Collins argues in his best seller Good to Great? Is it because successful companies have superior management systems and organizational cultures? Is it because of positional advantages, as Harvard’s Michael Porter might argue? Or is it all down to timing and luck?

Concluding that luck is a big factor would be unlikely to sell many paperbacks in an airport bookstore; yet, undoubtedly, chance events have played an important role in many successes and failures. For instance, the late Apple CEO Steve Jobs credited the success of the Macintosh (Apple’s personal computer) to a chance visit to the Xerox PARC laboratory in Palo Alto, California, in 1979, when Apple was still just a promising startup. As Malcolm Gladwell later recounted in the New Yorker, upon witnessing a Xerox engineer open and close “windows” on a Xerox Alto computer and move from one task to another, Jobs remarked, “Why aren’t you doing anything with this? This is the greatest thing. This is revolutionary.”

Returning to Apple’s offices, Jobs asked his engineers to change course: he wanted the Macintosh to have a graphical user interface and a mouse. The early Macintosh remains one of the most iconic products in Silicon Valley history, while Xerox, after some modest successes with the Alto, withdrew from the personal-computer market. Reflecting on his visit to PARC, Jobs said, “If Xerox had known what it had, and had taken advantage of its real opportunities, it could have been as big as IBM plus Microsoft plus Xerox combined and the largest high-technology company in the world.”

But chance events may be only part of the answer. Today’s superstar companies possess vastly superior capabilities, especially in information technology and data analytics, than everyone else. Dominance in these two areas enabled them to acquire the killer combination of scale and scope, serving millions of consumers with a wide variety of offerings.

By mastering data analytics and information technology, today’s leading companies employ a bottom-up, experimental approach to discovering the best answers to a range of management questions.

It is easy to bemoan the dominance of the superstars, and to blame concentration in some industries for the lack of innovation among smaller competitors. Yet even without the scale and dominance of the incumbents, there is much that companies can do to improve their own chances of success. Ultimately, what drives most of today’s superstar companies is that they have discovered the art and science of bottom-up innovation: lots of experiments, an emphasis on decentralization and learning, a tolerance for failure, and the application of leverage when the forces are with them. Nonsuperstar companies would do well to learn from this model.

And, of course, because capitalism is a dynamic process, success rarely continues forever. Business history offers a series of examples of a sobering lesson: superstar status today does not shield a company from failure tomorrow. That iconic companies of yesteryear such as Xerox, Kodak, Sony, Sears, and General Motors have lost their luster suggests that the economic and technological forces that propel superstar companies to the top of the heap are double-edged swords. Indeed, the destructiveness of these forces, often hidden by companies’ successes, may gain momentum just when superstar companies have hit their peak.

Lessons from ecology

Ecology provides an explanation for why some species survive and thrive while others do not. Consider the fitness-landscape model, developed by the University of Chicago geneticist Sewall Wright. Wright’s model assumes that the attributes of a species—let’s say, a gazelle—contribute to its fitness, and that individual members of the species differ in the quality and quantity of each attribute.

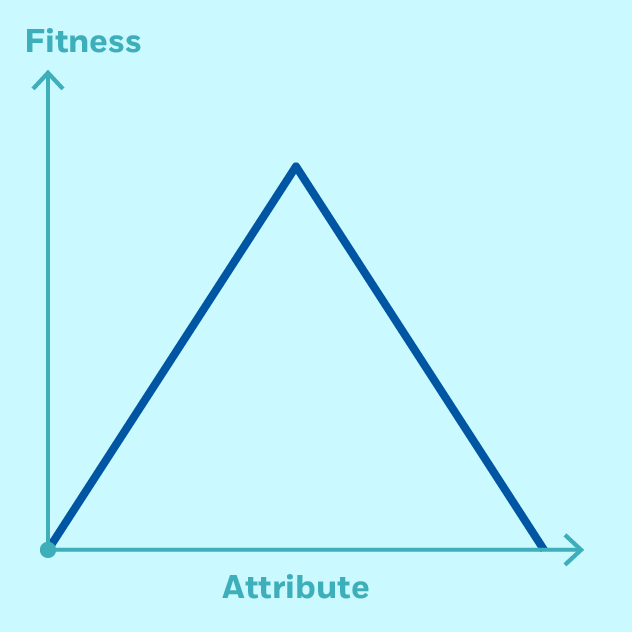

A fitness landscape measures fitness (reproductive ability) on the vertical axis and an attribute (for example, the thickness of a gazelle’s legs) on the horizontal axis. If a gazelle has no legs (a score of zero along the horizontal axis), it cannot survive, and its fitness score is zero. Gazelles with legs have better scores, and those with thick and robust legs have increasingly higher scores. But beyond some point, additional thickness begins to hurt a gazelle’s score. We can imagine a gazelle that has such thick legs that its mobility is fatally diminished, making its fitness score zero.

In the illustration below, the fitness landscape resembles Mount Fuji. Evolutionary scientists view Mount Fuji problems as easy to solve because adaptation and selection pressures converge on the optimal value for the attribute, in this case, the ideal leg thickness in gazelles (as a species). Viewed as an optimization problem, any hill-climbing algorithm will detect the peak.

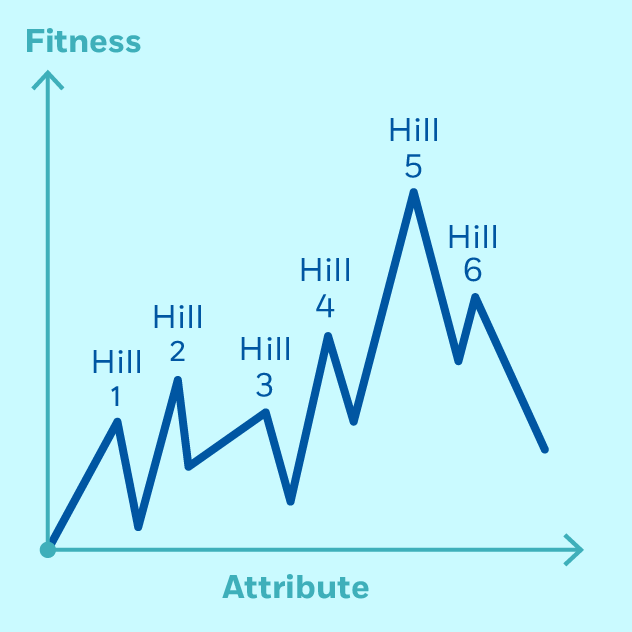

So far, so good. But species have more than one attribute. When a fitness score depends on multiple attributes that interact with each other—such as the size of the gazelle’s body, the size and shape of its head, the sharpness of its teeth, etc.—the fitness landscape resembles a rugged landscape. The greater the interaction among the attributes, the more rugged the landscape.

The rugged fitness landscape

In a rugged fitness landscape, the peak of each hill corresponds to a particular combination of attributes. At a given point in time, there is considerable diversity within the species: some gazelles have thinner legs and smaller bodies, and some gazelles have bigger legs and bigger bodies. In the illustration below, Hill 5’s peak has the highest fitness score; other peaks have lower fitness scores.

In a 1997 paper, University of Pennsylvania’s Daniel Levinthal adapted Sewall Wright’s model to analyze the evolution of industries. Change in any given industry occurs because of organizational adaptation (the deliberate attempt by companies to acquire new attributes), Levinthal argued, as well as population-level selection effects (through the birth and death of companies).

To understand how this works, think of market value as a proxy for fitness. It’s clear that market value depends, among other things, on the attributes deliberately chosen by a company, such as the quality of its leaders and managers, its organizational culture, its management practices, its products and services, and so on. The collection of attributes chosen by the company provides a snapshot of its strategy.

The challenge for corporate leaders is that companies have to navigate the rugged landscape without an aerial view of it. Consequently, the character of the company, including its aspirations, purpose, and strategy, is shaped by the limited view that managers and entrepreneurs have of their landscape. For instance, each of the 37 health-care companies in the 2018 Inc. 500 list (of the fastest-growing US companies) operates in distinct product, service, and geographic markets. These are very varied. They include supplements and superfoods, surgeries, retinal eye exams, yoga classes, animal hospitals, surgical implants, gene delivery, telemedicine, dental impressions, and autism therapy. Evidently, the entrepreneurs at the 37 companies had distinct assessments of the opportunities in the health sector.

Our illustration of the rugged landscape highlights that where one starts matters. Companies that start with attributes close to the origin will more than likely choose to climb Hills 1 or 2 and find it difficult to alter their strategy sufficiently to climb Hill 5. Some companies that start with attributes much further away from the origin will more than likely choose to climb Hills 5 or 6. The ruggedness of the landscape implies diversity in strategies, with some companies settling on strategies that are less risky and yield modest market value (smaller hills that are easier to climb), and a few companies going for strategies that are more risky and yield high market value (bigger, harder-to-ascend hills).

The dancing rugged landscape

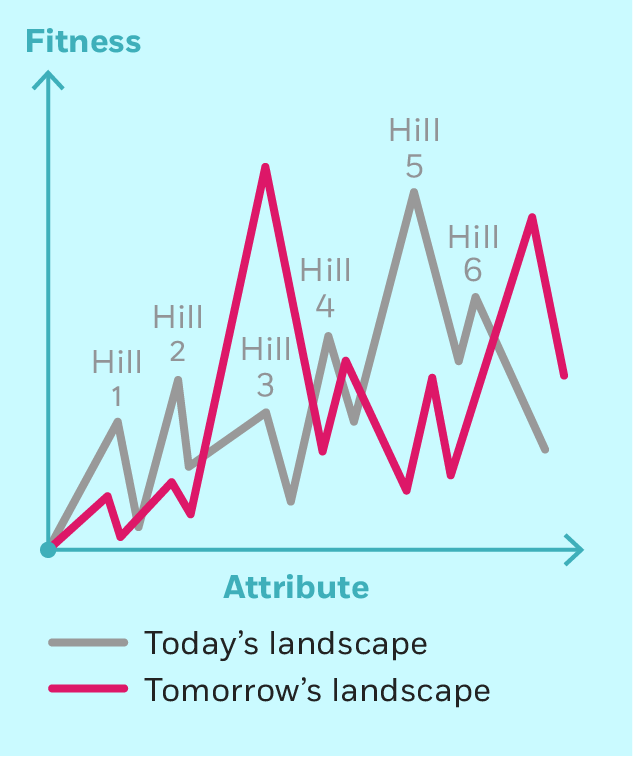

There is another complication. The rugged landscape keeps shifting; it’s a dancing rugged landscape. The shape of the landscape depends on the choices of all companies: as companies within an industry alter their strategies, the rugged landscape alters. A company that finds itself on the highest peak today may find itself on a smaller hill tomorrow, while today’s startup may be at the top of the highest peak tomorrow. This is what happened to Research In Motion, the pioneer in smartphones, whose CEOs in 2007 dismissed the potential of the Apple iPhone and Android phones to threaten BlackBerry’s primacy. From a market share of 44 percent in 2007 (when the iPhone was first introduced), Blackberry’s market share today is zero.

Why companies fail

Failure in the rugged-landscape model shows up in two ways: companies are unable to climb a hill, or they pick the wrong hill to ascend.

Typically, companies are unable to climb a hill (or to move from one hill to a neighboring hill) because they lack the required competencies and management systems. In a 2013 paper analyzing the quality of management practices at over 6,000 companies in a dozen countries across the world, Stanford’s Nicholas Bloom and MIT’s John Van Reenen find that there is substantial variation within and across countries. In a separate study, they and their coauthors find that even in the United States, whose management scores on average are among the highest in the world, 27 percent of organizations (from a sample of 70,000) made use of fewer than half of the structured management practices identified by the researchers. In a 2013 paper on which Bloom is the lead researcher, interviews with personnel at textile manufacturers in India who received poor management scores revealed that managers were often unaware of modern management practices. And even when managers are aware of these practices, history and experience have shown that they are often unable to execute.

The other reason companies falter in rugged landscapes is their discovery that there is little or no reward for having reached the top of a hill. The company may have done all the little things right but got the big thing wrong: it has climbed the wrong hill. Such strategic failures can be devastating, and often prompt much soul-searching about what went wrong, and when.

The slow-motion failure of Sears, which filed for bankruptcy in 2018, illustrates the cumulative effect of poor decisions that stretch across decades. From the 1940s to the ’80s, Sears was the biggest retailer in the world. Looking back, it is evident that the ’60s were the apex years. In 1969, two-thirds of the US population shopped at Sears, and half of US households had a Sears credit card, according to Fortune. Sears’s market value (measured in 2019 dollars) peaked in 1965, when it was worth $92.1 billion.

The company’s first strategic error was that Sears’s planners viewed the landscape and concluded that retailing was not the future, and that they could reap bigger rewards in financial services. The plan was for Sears to cross-sell financial services to its increasingly affluent and large customer base.

In 1981, Sears bought Coldwell Banker, the residential real-estate brokerage company, and Dean Witter Reynolds, the stock-brokerage company. Both acquisitions failed, and by the mid-’80s, both Coldwell Banker and Dean Witter remained unprofitable. Damningly, the focus toward financial services meant that the retail business was now a second-class citizen. While Sears had been embarking on this path, rival retailers such as Walmart, Target, Home Depot, and Best Buy had been rapidly expanding across the US.

By 1991, it was evident that the corporate diversification strategy had failed: Sears’s market value had fallen by 80 percent from its 1965 peak. There would be no way back. The retail momentum was now on the side of Walmart and other new competitors. The following year, Sears spun off Coldwell Banker, Dean Witter, and Allstate.

Why companies succeed

Companies that successfully climb, and stay, on the highest peaks clearly do the routine things as well as the occasional-but-significant things better than others. By mastering data analytics and information technology, today’s leading companies employ a bottom-up, experimental approach to discovering the best answers to a range of management questions. What do consumers want? What is the optimal size of work groups? What composition of work groups is most effective? What incentive schemes elicit the best effort from individuals and groups? Theory and knowledge alone may provide poor answers to these questions. An approach that embraces discovery, failure, learning, and adaptation generates better answers faster.

Alphabet epitomizes the data-driven approach to decision-making. According to Matthew Syed’s book Black Box Thinking, to discover the “optimal” color on the Google toolbar, the one that produces the maximum number of clicks, Google conducted a randomized control trial in which it randomly assigned Gmail users to one of 40 groups, with each group being exposed to a toolbar with a different color. The result: Google discovered that optimal color for the toolbar without resorting to theory or gut feeling.

Google has employed this experimental approach in pursuing big-bang strategic projects as well. Products such as Gmail, Google News, and Adsense started as modest experiments that were expanded only after each product achieved milestones. The willingness to explore widely to discover the best ideas is reflected in the more than 225 firms that Google has acquired since 2001. To be sure, many of these acquisitions have been failures; but some, such as YouTube and Android, have been spectacular successes.

Navigating the dancing rugged landscape is part art and part science, and there is no formula for climbing and staying on the top of the biggest peaks. But there are four things worth bearing in mind as your organization plots its path through the terrain ahead: the importance of listening and engaging with a wide variety of models and people; being ready to change one’s opinion; cultivating an opportunistic decision-making style; and doubling down on what is proven to have worked. Successful organizations do not always progress in a linear fashion, but they tend to come back to a methodology that is open, flexible, and experimental.

Ram Shivakumar is adjunct professor of economics and strategy at Chicago Booth.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.