How to Get a Company off the Ground

The Traction Gap is defining the second stage of new-venture creation.

How to Get a Company off the GroundWhat makes Shark Tank, the business-pitch TV show, so compelling? The drama of watching people advocate for their fledgling companies to potential investors can, of course, be quite entertaining. But many founders can also learn something from watching these mini pitch meetings. The questions the sharks most frequently ask center on the entrepreneurs’ plans to scale their startups:

The responses help the sharks assess the advantages (if any) that accrue with size; the likelihood that the entrepreneurs have the skills, connections, and mental toughness to survive the hazardous journey of scaling up; and the risks and potential rewards of an investment in the company.

For every startup that scales up, thousands fail to do so. Some 65 percent of VC deals returned less than the capital invested between 2004 and 2013, according to a 2014 study by Correlation Ventures. In fact, the best-performing VC funds had more strikeouts than poorly performing funds did. For funds that generated returns greater than 500 percent, fewer than 20 percent of deals generated roughly 90 percent of the funds’ returns. The headline news was captured by the four out of every 1,000 deals that generated a 10,000 percent return or more. As Bill Gurley, one of Silicon Valley’s most successful venture capitalists, has noted, “venture capital is not even a home-run business; it’s a grand-slam business.”

This is why investors carefully evaluate every deal on its own terms, examining in particular the company’s potential to go big. Of special interest are a company’s projected sales revenues and customer acquisition costs, its projected unit costs as it scales up, and the projected capital burn rate. The faster the company can acquire customers and the lower the costs to acquire them, the faster the company can get to profitable growth. The lower the company can get its unit costs, the greater the potential to reduce prices and increase volumes as well as profits. And the smaller the capital burn rate, the longer the company can survive to go on to test its hypothesis.

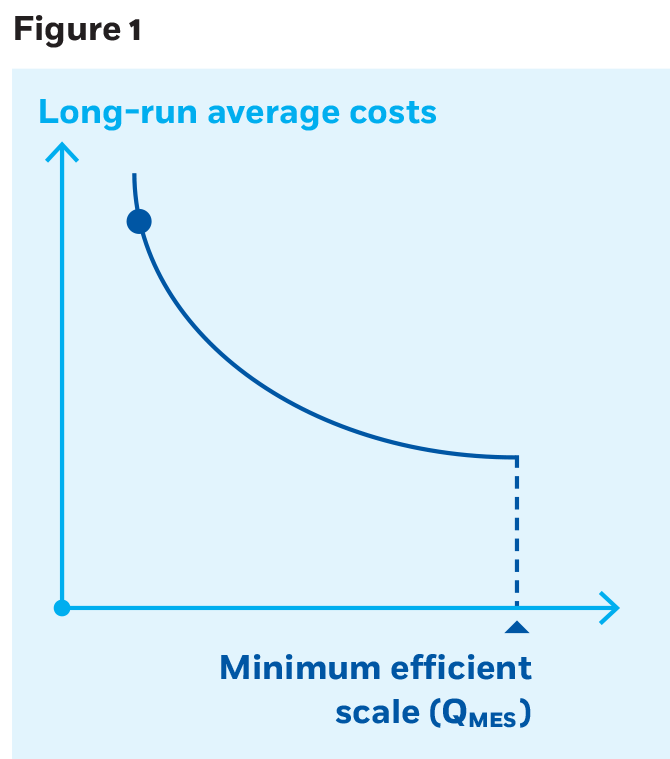

Economies of scale, a concept discussed in every microeconomics textbook, refers to the capacity of a company to produce ever more units of a product at lower average (or unit) cost. The textbook depiction of economies of scale is a declining average cost curve, as production efficiencies enable the company to spread its fixed costs.

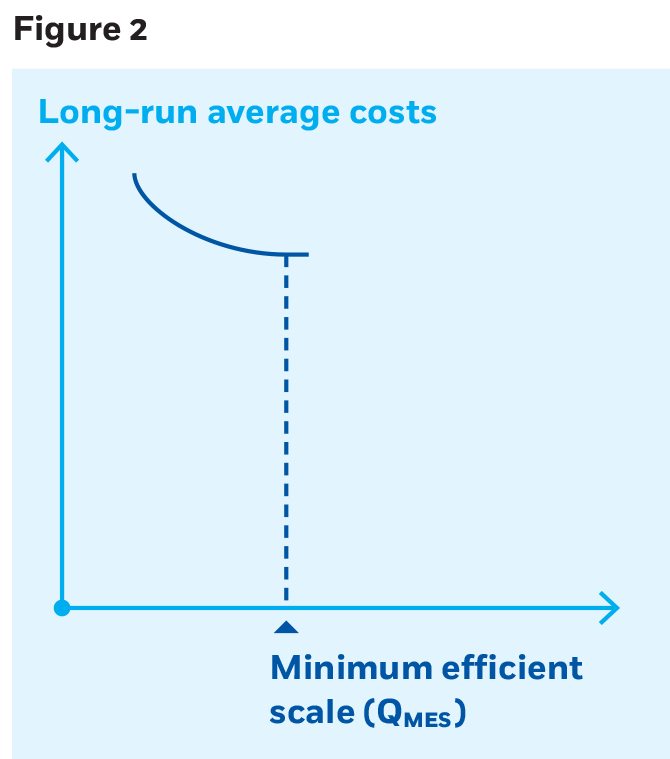

Entrepreneurs and investors want to know two things, neither of which can be determined with precision at the outset. The first is whether the average cost curve for a specific product or service will decline steeply or be relatively flat. The second is the magnitude of the minimum efficient scale, the smallest production volume at which the company achieves scale.

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate two possibilities. In Figure 1, scaling up from Point A to Point B, where the company reaches minimum efficient scale (QMES), involves a significant decrease in unit cost as well as a significant expansion in volume. A company that successfully scales up to Point B along this average cost curve has the potential to serve a large customer base and dominate the market.

In Figure 2, scaling up to Point B from Point A involves a modest reduction in unit cost and a modest expansion in volume. In this case, scaling up leaves the company with fewer compelling advantages relative to the competition.

The process of scaling up is a much more complex endeavor than is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. The venture capitalist Paul Graham observes, “Bad [stuff] is coming. It always is in a startup. The odds of getting from launch to liquidity without some kind of disaster is one in a thousand.”

Scaling up only occurs after the company has discovered and mastered a repeatable process that is both effective and efficient: effective in the sense that it is producing a product or service at the quality that consumers expect and are prepared to pay for, and efficient in the sense that the unit cost of production falls significantly at higher volumes.

This repeatable process is rarely obvious at the start. In the early years of the automobile industry, around 1895, more than 80 US companies vied to produce a car, each with its own distinct product designs and processes. At that time, annual industry production rarely exceeded a few thousand units, as these startups struggled to master product and process. Even as late as 1905, state-of-the-art manufacturing required car bodies to be delivered by horse-drawn carriages while workers rotated from one station to another doing their assembly tasks.

In 1913, Ford Motors introduced the first moving assembly line, supported by a winch and a rope stretched across the floor. The process of assembling more than 3,000 parts of the chassis was broken down into 84 sequential steps involving 140 workers. By 1916, the moving assembly line had improved significantly, which meant that the annual production volume of Ford’s Model T had grown substantially, and the price of the car dropped from $850 to $300.

Successful scaling requires companies to acquire expertise in four competencies. Without these, companies are unlikely to cross the chasm from promising startup to serious contender.

In 1906, Ford produced 8,729 cars. Ten years later, it produced 734,811 cars, an 84-fold increase. In 1996, Amazon received a few hundred orders for books each day. Today it receives more than 2 billion orders each day for same-day or next-day delivery. In 1987, Starbucks operated six stores in Seattle. It now operates more than 30,000 stores worldwide.

None of this would have been possible without a great deal of learning. Institutionalizing a learning culture is a challenge with five components:

View learning as a journey: What is underemphasized in most stories of scaling is the journey of learning. This includes learning the things that work as well as the things that do not, a process that prepares entrepreneurs to distinguish promising opportunities from less-promising ones. Analyzing the lessons of each experience and modifying management practices accordingly can help companies become better, faster learners.

Let experience be your teacher: Learning by doing, an educational philosophy championed by philosopher John Dewey, posits that learning is most substantive and enduring when the learner is forced to interact with the real world. Mark Cuban, an entrepreneur and Shark Tank shark, argues that in business, knowledge and skill can only be obtained by practice. This is why the Nike slogan, Just Do It, is a simple as well as profound call to action.

Embrace experimentation: As Tim Harford, the Financial Times columnist, observes, “when a problem reaches a certain level of complexity, formal theory won’t get nearly as far as an incredibly rapid process of trial and error.” Successful scaling requires companies to conduct many experiments, observe processes and outcomes, and iterate. Chicago Booth’s Harry L. Davis has championed a portfolio approach to innovation: running lots of carefully chosen small-scale experiments. This requires asking (and answering) many questions: How many experiments should we run? When should we abandon an experiment? When should we continue with an experiment? And what criteria should we use to decide? Experimenting with different processes led the engineers at Ford Motors to conclude in 1916 that producing a car effectively and efficiently required 84 steps, and not 78 or 89.

A company’s culture is like the plumbing system: if it isn’t maintained, it will deteriorate.

Be ready to fail: Learning how to deal with failure is a vital organizational attribute that separates successful scalers from unsuccessful ones. The cost of avoiding small failures is often big failure. Only a handful of the more than 200 companies that entered the automobile industry in the late 19th and early 20th centuries survived beyond 1920. As Reid Hoffman, the entrepreneur, notes, “if you tune it so that you have zero chance of failure, you also have zero chance of success. The key is to look for ways for when you get to your failure checkpoint, you know to stop.”

Learn faster than your rivals: Arie de Geus, former head of Shell Oil’s strategic planning group, observes that “the ability to learn faster than your competitors may be the only sustainable advantage.” The bigger the potential prize, the more intense the competitive race is to scale up. The list of innovators that were able to create the first prototype but were upstaged by later entrants in the race to bring the product to the masses is long. Leica introduced the first still camera, but Canon was the first to create a mass market for it. EMI was the first to develop the CT scanner, but GE used its distribution and marketing muscle to commercialize the product first. BlackBerry dominated the smartphone market from its inception until 2011 but was unable to keep up with the software and hardware innovations introduced by the Apple iPhone and Android phones.

Small companies have informal organizations for a very good reason: they need to pivot when circumstances dictate. Consequently, their organizational structures are flexible, management practices are not codified, employees don many hats, and decision-making authority is concentrated in the hands of a few people.

Scaling up, however, requires an organizational reboot.

Assess the competency gap: Begin with an audit of competencies—identify those the company possesses and those it does not. Scaling up requires explorers, who excel at discovering new things, as well as exploiters, who are good at repeated tasks. This requires specialization. The people hired to be explorers must be entrepreneurially inclined, while those hired to be exploiters must have operational competence. Explorers should focus on innovation and growth, while exploiters focus on cost optimization and profit maximization. While most startups likely have many explorers among their employees, they often lack exploiters.

Formalize organizational structure: Scaling up requires discipline, which, in turn, requires a company to formalize its organizational structure by explicitly assigning authority and responsibility, and delegating decision-making. The value of a formal organizational structure is greater in an ever-more complex world in which the manufacturing of smartphones, automobiles, software, and other products depends on global networks of competencies. Organizational structure enables cooperation, coordination, and accountability as companies grow. Some collaborations are easier to foster than others. What makes for difficult collaborations is that knowledge and skill are often diffused and tacit. In his 2015 book, Why Information Grows, MIT’s César Hidalgo persuasively argues that the ability to combine tacit knowledge is a source of sustainable competitive advantage.

Tighten operational planning: In his 2018 book, Measure What Matters, John Doerr, chairman of Kleiner Perkins, the Silicon Valley VC firm, recalls his early investment in Google and his initial assessment of the company: great product, high energy, big ambitions, and no business plan. Doerr recalls that what Google badly needed was a system to prioritize decisions and a way to track progress on initiatives. So Doerr proceeded to teach Google founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page (and others) the OKR (objectives and key results) model that he had learned at Intel. The OKR model helps companies articulate their objectives and spell out the set of actions that the company must take to achieve those objectives. Doerr argues that the OKR model works because everyone is aware of the company’s priorities as well as every team’s responsibilities, and each team is incentivized to coordinate its actions to solve the company’s most pressing problems.

Reinforce culture: The late Herb Kelleher, the founder and former CEO of Southwest Airlines, considered the company’s culture to be what separated it from other US airlines, telling two Fortune editors:

It’s the intangibles that’s the hardest thing for a competitor to imitate. You can get airplanes. You can get ticket counter space. You can get tugs. You can get baggage conveyors. But the spirit of Southwest is the most difficult thing to emulate. So my biggest concern is that somehow, through maladroitness, through inattention, through misunderstanding, we lose the esprit de corps, the culture, the spirit. If we do ever lose that, we will have lost our most valuable competitive asset.

Many employees fondly recall their early days (and nights) in a startup: the camaraderie, the free-flowing exchange of ideas, the flat structure. But culture is threatened when the startup takes on new employees, introduces hierarchies, and restructures. Reiterating a company’s mission and values is one step toward invigorating the culture. More important is sharing stories, celebrating personal and professional accomplishments, fostering opportunities for collaboration, and having honest and direct conversations on difficult issues. A company’s culture is like the plumbing system: if it isn’t maintained, it will deteriorate.

Most startups have had to pivot in small and big ways to find a winning business model. Among the questions that the startup must frequently answer: What business are we (should we be) in? Who are our target customers and what do they want? What is our product? What does the consumer pay for? And how does she pay: a one-time fee or a recurring fee? How are we creating economic value? And how are we capturing it?

The list of startups that have successfully pivoted is short in comparison to those that were unsuccessful. Twitter started as Odeo, a company devoted to podcasting, but pivoted to become a microblogging platform after observing that iTunes was bent on entering the podcasting space. Instagram started as Burbn, an app that combined gaming with photography, but simplified its business to focus on photography alone.

Creating a market requires a scaling company to acquire several related skills:

Iterate to the right product: Changing customer needs, competencies (or lack thereof), and competition force companies to iterate until they find a product offering that has a chance at success. The original owners of Starbucks, Jerry Baldwin, Gordon Bowker, and Zev Siegl, wanted to be in the coffee-roasting business, but Howard Schultz, who acquired Starbucks in 1987, wanted to be in the coffee-bar business. Schultz’s dream was to recreate the experience of an Italian coffee bar in the United States, at scale. After a great deal of iteration, Schultz and his team settled on the characteristics of the Starbucks product: high-quality coffee beans, strong aroma of coffee, fast service, a friendly barista, and a limited food menu. When the Honda Motor Company first entered the US market in 1958, it intended to sell large motorbikes. Visits to dealers and distributors led to the discovery that consumers were not interested in large motorbikes, though they were interested in the smaller motorbikes that members of the sales team were using to reduce the cost of commuting.

Discover customer-product fit: Successful scalers often attribute their successes to getting the “right” customer. The right customer views the problem the company is trying to solve as vital to his or her own performance; the right customer is likely to positively influence the decisions of other customers; and importantly, the right customer enables the company to make a profit. Conversely, a costly mistake is acquiring the “wrong” consumer: someone who is unlikely to be a repeat consumer, whose needs are incompatible with the product offering, or who is unlikely to influence the purchase decisions of other consumers. Reflecting on the pivotal moments during his years as CEO of Fieldglass, an enterprise software company that was acquired by SAP in 2014, Jai Shekhawat told me that an important lesson from early failures was to learn to distinguish the right customers from the wrong customers. “You don’t want to do a beta test with a customer that has no intention of being your customer,” says Jai. “And you don’t want to take on customers who force you far afield from your company’s mission and competencies.”

The skills required to scale up a company are distinct from those needed to launch one successfully, which is why founders often depart when their companies start to grow seriously.

Discover product-channel fit: One of the more-contested periods in a Shark Tank episode centers on the entrepreneurs’ go-to-market strategy. The sharks often argue with the entrepreneur as well as with each other on the relative merits of alternative channels. Each shark plays up the strength of his/her expertise in channel selling while gently mocking the channel network competencies of the other sharks.

The right channel partners operate quickly; put the company’s products in the hands of the ideal customer; help the product achieve greater name recognition; and, importantly, help the company grow its reputation and bottom line. In contrast, the wrong channel partners damage a company’s prospects: they dilute the brand value by mispositioning the product or, in many cases, they waste valuable time by doing nothing.

Startups in a range of industries from software to manufacturing often rely on bigger competitors to bring the product to market. Small biotechnology companies often enter into partnerships with large pharmaceutical companies to commercialize their products; small retailers use the Amazon marketplace to sell their products; and small software companies often rely on large software and information-technology-services companies to market and distribute their products.

However, reliance on a single channel partner is risky. A former Booth student of mine, Jill James, who now runs growth-advisory company Sif Industries, describes the channel challenge for startups as follows: “I think of early-stage channel strategy as finding your frenemies: you’ll work together for now, but if things go well, you’ll directly compete or even put them out of business. You do what you need to do on the way up to build scale until you can have the means to control the channel.”

Going from prototype to scale (or niche segment to mass market) requires capital. Often, the capital required is far greater than can be bootstrapped by the entrepreneur. Many entrepreneurs raise seed (equity) capital from family members, friends, and angel investors and debt capital (loans) from individuals, credit cards, banks, and alternative-lending platforms such as LendingClub.

For the entrepreneur contemplating a venture investment to support the scaling-up journey, it is important to answer a couple questions:

Is my company a fit for venture capital? In his recent book, Secrets of Sand Hill Road, Scott Kupor, the venture capitalist, says that one of the first questions entrepreneurs must answer is whether venture capital is right for them.

Just as with product-market fit—where we care about how well your product satisfies a specific need—you need to determine whether your company is appropriate for venture capital. No matter how interesting or stimulating your business, if the ultimate size of the opportunity isn’t big enough to create a stand-alone, self-sustaining business of sufficient scale, it may not be a candidate for venture financing.

Venture capital is a better source of capital than loans for most startups that are scaling up because they are unlikely to generate positive cash flow, have a high probability of failure, and will likely experience prolonged periods of illiquidity. But venture capital comes with strings. Not only will the entrepreneur have to give up a portion of his equity stake, the entrepreneur will have to share decision-making rights with the venture capitalists.

How much capital should we raise? As Scott Kupor says, “the answer is to raise as much money as you can that enables you to safely achieve the key milestones you will need for the next fund-raising.” What the key milestones have in common is that risk is reduced: the startup has developed its products, acquired key customers, and met some financial and operational targets. Hitting these milestones means that the next round of investors will reward you with a higher valuation.

One school of thought says that companies would do well to avoid raising too much capital. Reflecting on the $38 million that he raised for Fieldglass over six years, Shekhawat told me, “In hindsight, we probably raised about $8 million more than we needed, which makes for expensive equity at the relatively modest valuations back then.” David Packard, the founder of Hewlett-Packard, famously observed that “more companies die of indigestion than starvation.” What he was trying to say was that companies without a great deal of capital are forced to make the hard economic choices that serve as the catalyst for innovation.

Another school of thought is that companies should raise as much capital as they can, when they can. Reid Hoffman and author and investor Chris Yeh articulate the logic for this view in their most recent book, Blitzscaling. Raising enormous amounts of capital, in their view, acts as a signal to the financial markets that the company has increased the probability of locking up its market and building a dominant position. The emphasis, they argue, should be on acquiring a strong user base—if necessary, at the expense of profits. The archetype company that has employed this model is Uber, which raised $24.3 billion over the 12 years prior to its 2019 initial public offering. Sidecar, the company that introduced the peer-to-peer taxi-service model in 2012, raised a comparatively puny $35.5 million, was unable to match the scale of Uber’s investments, and was forced to exit.

The skills required to scale up a company are distinct from those needed to launch one successfully, which is why founders often depart when their companies start to grow seriously. Our culture tends to downgrade the former and revere the latter. Startup founders are the stars of Silicon Valley, while successful scalers are sometimes spoken of as if all they have done is merely manage someone else’s idea. In this startup age, it’s time to correct this imbalance. True business success only comes when an idea can be demonstrated to work on a large and growing scale.

Ram Shivakumar is adjunct professor of economics and strategy at Chicago Booth.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.