During this year’s Democratic presidential primaries, numerous candidates championed the idea of forgiving some or all of the student debt held by the federal government. Massachusetts senator Elizabeth Warren proposed canceling up to $50,000 in debt for nearly all borrowers; Vermont senator Bernie Sanders advocated wiping away all student debt. Now that president-elect Joe Biden, who has endorsed some measure of debt forgiveness, is set to take office on January 20, 2021, the notion of canceling student debt has only gained momentum.

But who benefits from such forgiveness would depend largely on how it’s structured. Some policy approaches could chiefly benefit the highest earners, suggests research by University of Pennsylvania’s Sylvain Catherine and Chicago Booth’s Constantine Yannelis.

In the United States, about 43 million borrowers collectively owe nearly $1.6 trillion in outstanding federal student debt, according to the Department of Education’s office of Federal Student Aid. That balance has more than tripled since 2007, while the number of borrowers has only increased by about 50 percent.

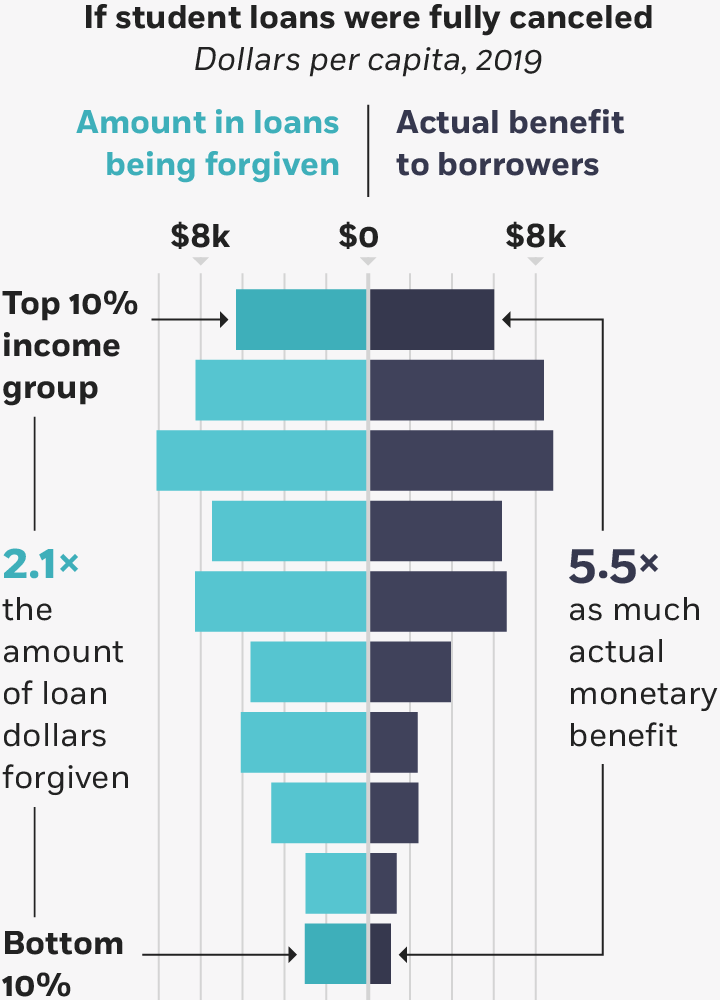

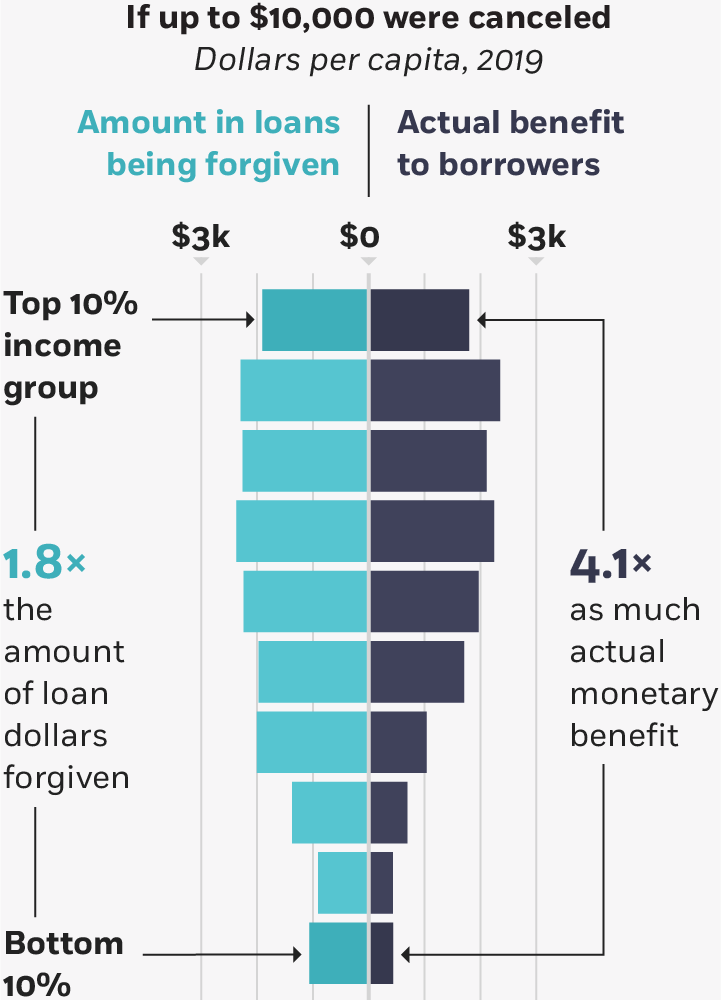

There are a number of ways policy makers could go about relieving some of this burden, and Catherine and Yannelis focus on three broad approaches to debt cancellation: universal forgiveness (canceling all student debt for everyone), capped forgiveness (canceling up to $10,000 or $50,000 of every borrower’s student debt), and targeted forgiveness (wherein borrowers’ relief is tied to their income). Using data from the Federal Reserve Board of Governors’ 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, the researchers examine how student debt is distributed throughout the income spectrum, and how that would define the beneficiaries of various debt-relief plans.

They find that following universal student-debt forgiveness, the average person in the top decile of the earnings distribution would receive more than five times as much relief as the average person in the bottom decile, and almost half of all relief would go to people in the top 30 percent of the distribution. “Patterns are similar under policies forgiving debt up to $10,000 or $50,000,” they write, “with higher-income households seeing significantly more loan forgiveness.”