Partisan Bias Affects What Americans Think of the Coronavirus

- By

- April 16, 2020

- CBR - Economics

There’s a distinct difference in the way Americans react to the threat of the coronavirus pandemic, research suggests. “Even when—objectively speaking—death is on the line, partisan bias still colors beliefs about facts,” write Chicago Booth’s John Barrios and Rice University’s Yael V. Hochberg.

As COVID-19 rages, governments have supplemented the search for a vaccine with a behavioral tool: social distancing. The hope is that reducing nonessential business activity and travel, through “shelter-in-place” orders and other mandates, will reduce the spread of the disease.

But getting people to stay home and avoid social contact requires a coordinated effort, and though health officials have recommended voluntary restrictions, some people have taken the threat more seriously than others. While many canceled travel plans because of stay-at-home orders, others gathered in Florida for spring break. That’s problematic because when people travel and gather in groups, it potentially affects their health but also that of anyone they encounter, increasing the risk that they will expose their neighbors and others to the virus.

In the face of a shared public-health threat, why do some people react differently than others? To find out, the researchers looked at data on internet searches, using Google Trends to measure searches for terms that included coronavirus, COVID-19, and Wuhan virus. Presumably, when people searched for information on the virus, they were thinking about the risk associated with the pandemic and were considering steps to address it. The researchers also captured search trends for terms related to unemployment, such as benefits and insurance, to track people’s sense of economic risk related to the pandemic.

They find a link between politics and searches. The higher the share of voters who supported US president Donald Trump in a county, the less that people in that county were concerned with COVID-19.

Less social distancing in places with more Trump voters

Research suggests that there was less concern about COVID-19’s spread during February–March 2020 in US counties in which Donald Trump had a greater share of the vote in 2016.

Barrios and Hochberg, 2020

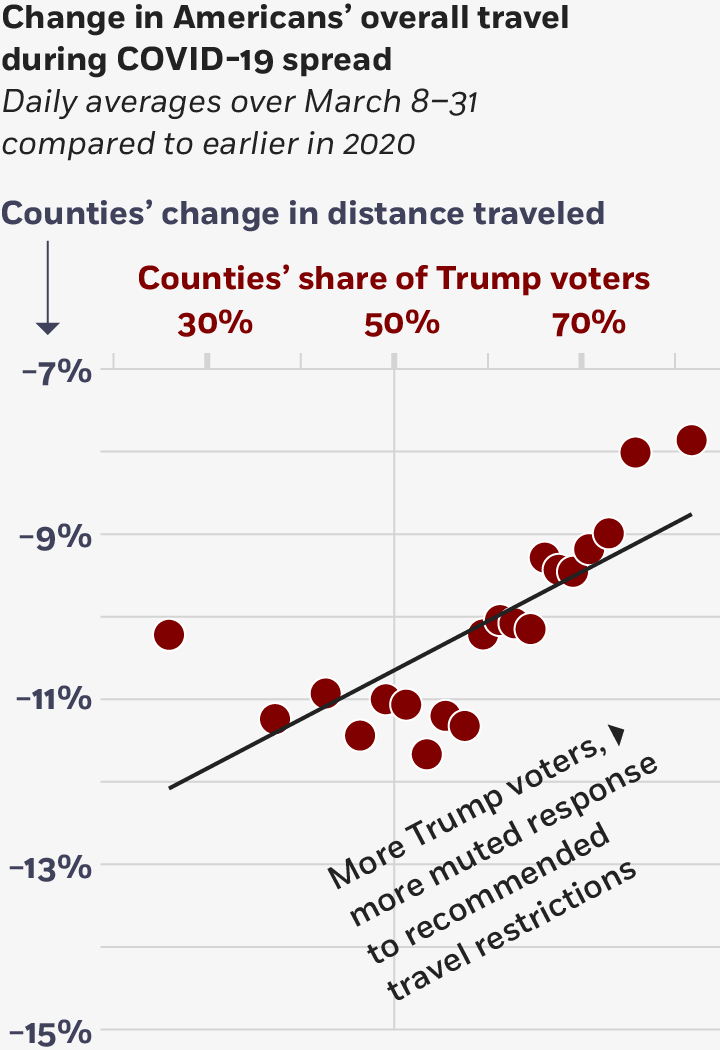

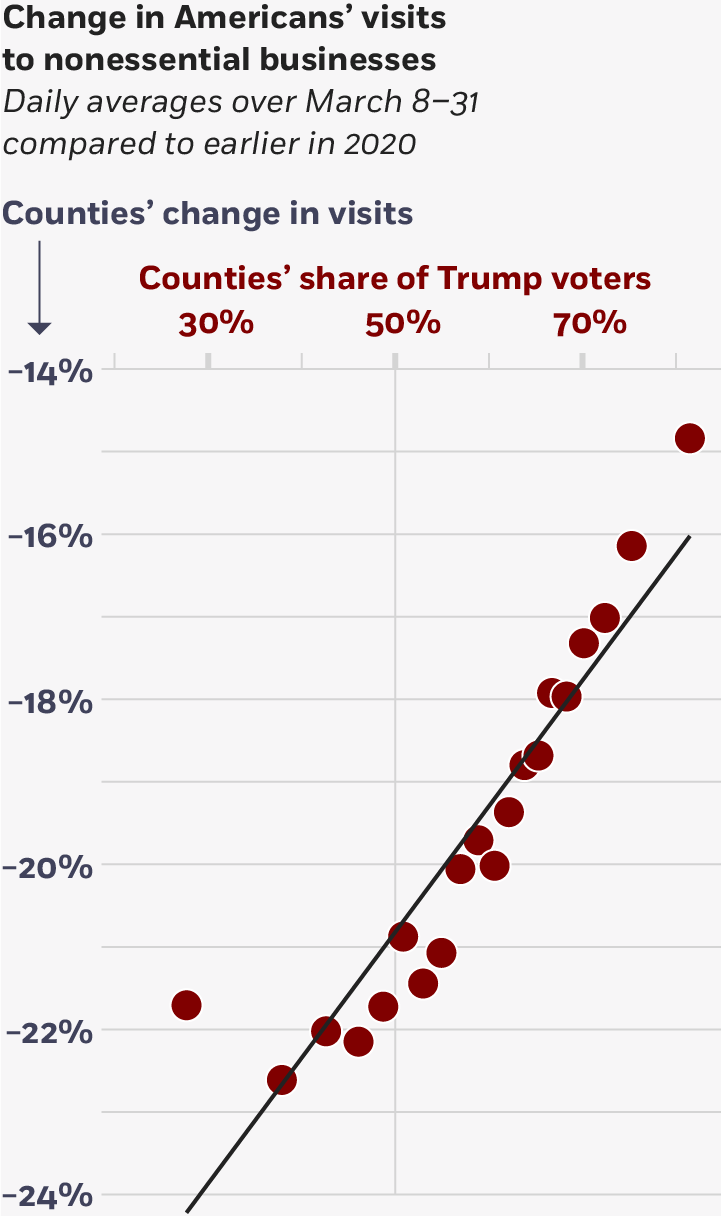

Barrios and Hochberg also used anonymous, national mobile-phone data from the location-data-products company Unacast to measure daily social-distancing trends. They analyzed changes in distance traveled and visits to nonessential retail and services locations, comparing patterns from the prepandemic period of February 24 through March 8 and the pandemic period through March 31. To proxy individuals’ political partisan affiliation by county, they relied on 2016 US presidential election data from the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, calculating the share of voters in each county that voted for Trump. Once again, they see a similar story: places with more Trump voters were less likely to practice social distancing.

The results hold when the researchers controlled for factors such as population density, to rule out that rural and urban voters might react differently because of where they live, and the ability of people to work from home. Two people in the same area, who had a similar ability to work from home but opposing politics, tended to react differently.

This trend has to do with the media that Democrats and Republicans consume, the researchers argue. On March 9, news broke that prominent Republican figures were quarantined following their COVID-19 exposure at the annual Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) meeting. Barrios and Hochberg considered search shares for COVID-19, before and after the announcement about exposure at CPAC, as a function of the average ratio of searches for right-leaning Fox News to left-leaning MSNBC across designated market areas. In the pre-CPAC period, there were few Fox News searches for COVID-19. But this reversed post-CPAC, consistent with Fox News viewers perceiving risk differently once people in their party were affected.

In places with more Trump voters, residents had exhibited a muted response to preliminary COVID-19 cases, even as state governments imposed a variety of school and business closures and stay-at-home recommendations. After March 9, those residents began to reduce travel and visits to nonessential businesses.

The researchers don’t take a view as to whether Republicans were underreacting or Democrats were overreacting to the health threat but note a relationship between politics and viewpoint. Conservative-leaning news outlets, affiliated with the party in power, may have had an incentive to downplay the risk, as criticizing or disagreeing with party leaders could cost the party in an election year. Similarly, “it is also possible that the opposition party may exaggerate it [a potential pandemic] to galvanize the population to seek change or to argue that the party in power mismanages crises,” the researchers write. When party leaders and media outlets began to treat the risk differently than before, people at home in turn adjusted their beliefs and behaviors.

As countries struggle to flatten the curve of this pandemic, and consider how to react to future ones, the findings suggest policy makers need to take politics into account. If risk perceptions and, consequently, behavioral choices, are shaped by politics, both parties need to jointly support interventions that curb outbreaks.

John Barrios and Yael V. Hochberg, “Risk Perception through the Lens of Politics in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Working paper, April 2020.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.