The United States is in the middle of that rarest of events: a public conversation on accounting standards. Since 1970, public companies in the US have been required to report quarterly. The Securities and Exchange Commission is now considering changing that frequency to biannual reporting, and in December 2018 issued a request for public comment on the matter.

Admittedly, the issue isn’t exactly igniting the passions of the masses, but the implications of these discussions could significantly affect the US economy. For the first time in many years, policy makers are seriously reconsidering the rules on corporate financial reporting. The SEC is examining how to change the system to lighten the burdens on corporations, and to reduce what it calls the “overly short-term focus by managers” of listed companies.

My research suggests there would be great benefits to the US ending mandatory quarterly reporting. It would help to kick-start innovation among US companies, for one. That should be of particular interest to the SEC, which stated in its request that it is interested in how the current system “may affect corporate decision making and strategic thinking.”

The SEC’s study follows comments from President Donald Trump last year that US companies should be required to report only every six months rather than quarterly. Some would like to go further: moving from quarterly to annual reports would lead executives to focus more on the long run, according to about one-third of prominent economists polled by Chicago Booth’s Initiative on Global Markets. (See “Should companies report annually instead of quarterly?” Published online, February 2019.)

Lessening the frequency of reporting would certainly be popular with corporations. As Jamie Dimon, chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, and Warren Buffett, chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, observed in an opinion piece for the Wall Street Journal last year, “quarterly earnings guidance often leads to an unhealthy focus on short-term profits at the expense of long-term strategy, growth and sustainability.”

This discussion will be particularly welcomed by innovative listed companies for which quarterly reporting is not just burdensome but distortive. Truly innovative projects are inherently uncertain and risky, but public companies have to hit their quarterly earnings forecasts, and that requires them to reduce risk and uncertainty.

Elon Musk is an interesting case study here. The CEO of Tesla, the electric-car maker, settled charges with the SEC last year after speculating about going private. As part of the settlement, he had to pay a fine and give up the chairmanship of his company.

Musk is a colorful character, but simply attributing his comments to eccentricity risks missing the lesson embedded in this tale. His remarks about withdrawing from the public markets reflect a frustration felt by many listed companies that want to be truly innovative. Analysts focus on next quarter’s earnings. That isn’t a good time frame when you’re working on a big, bold, long-term project such as trying to fly tourists to the moon. That’s why Musk hates analysts. Privately, many other business leaders express similar frustrations.

My research demonstrates that quarterly reporting creates all sorts of distortions in how managers allocate capital.

In 2013, long before Musk got his knuckles rapped, Dell Technologies went private in a $24 billion deal that was the biggest buyout since the 2008–09 financial crisis. The personal-computer maker’s motivation was that chairman and CEO Michael Dell couldn’t deliver good quarterly results, and the company was at a stage in which, if it wanted to innovate, it needed to go private. It returned to the public markets in 2018 in a much healthier position.

Probusiness conservatives typically view the idea of reducing the frequency of financial reporting as one way to lower how much companies pay for compliance—one of the exogenous costs of doing business.

But in fact, the frequency of reporting has little impact here. Once a company has had to comply with regulations, additional reporting increases its budgets only minimally. And compliance costs have been falling over time, and are likely to continue to do so.

However, there is good evidence behind the SEC’s concern that quarterly reporting fuels short-termism. Managers are frequently rewarded with restricted stocks and similar perks whose value depends on quarterly earnings.

Every MBA student learns that stock market prices are forward-looking. But they are only accurately priced if markets fully capture a company’s risks, which means insiders and outsiders need to have the same information.

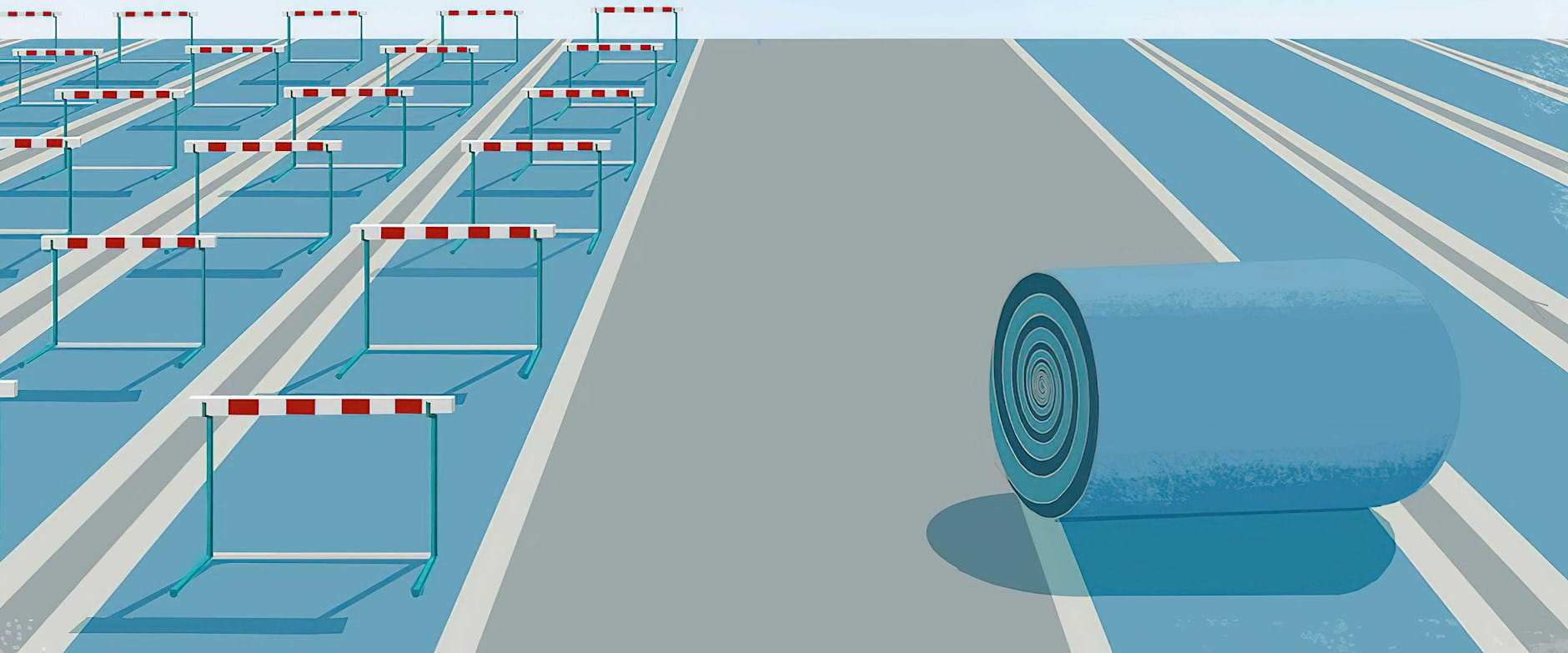

Line of Inquiry: How quarterly reporting distorts corporate investment

Yet we live in a world of information asymmetry. Outsiders—including most shareholders and analysts—don’t fully understand the nature of risk-taking within a company, so all they see are the earnings numbers. Those numbers give only a partial picture, which effectively means that share prices don’t fully reflect all the risks that businesses are taking—or not taking.

Liberal-leaning observers fret about losing transparency and accountability if companies report less frequently. This is a legitimate concern, and an important trade-off to consider in any rule change. It seems fair to say that we want more transparency rather than less in corporate reporting, and that less timely reporting would likely result in less market discipline.

But because the markets have such a quarter-to-quarter focus, more market discipline is only one side of the coin. In economic terms, market discipline ensures price efficiency (prices consistent with risk). However, there is a catch: such price efficiency may come at the cost of economic efficiency (increasing the size of the pie).

The really important cost of quarterly reporting is that companies underinvest in innovation, reducing economic efficiency. If we force companies to disclose frequently, they worry about their next earnings numbers. And if they miss expectations, they’re punished by the market.

In the race to hit quarterly expectations, companies cut back on research and development, and fail to focus on projects that will return their investment only over the very long run. CFOs report that the first thing they do in response to market pressure is to slash R&D budgets, according to a 2005 study by Duke University’s John R. Graham and Campbell R. Harvey and Columbia’s Shiva Rajgopal. The CFOs know that doing so destroys value, but it’s hard to communicate that with outsiders.

My research demonstrates that quarterly reporting creates all sorts of distortions in how managers allocate capital. They tend to overinvest in the wrong types of projects—those that produce short-term returns. What gets underfunded? The big, bold, innovative value-creating projects that will make a bigger impact but only in the longer run.

Less-frequent reporting would also give companies less of an incentive to go private and more of an incentive to go public. This would enable them to share risk with a broader pool of investors, and not just with big institutions and hedge funds.

Changing the frequency of reporting also provides the opportunity to ask whether one size should fit all. The SEC wisely suggests that companies could be given flexibility over the frequency of their reporting. We have an opportunity to run a grand experiment in accounting. Some companies could continue to report quarterly, some could move to biannual reporting, and others to alternative time periods, such as every four months. This would enable us to truly measure the costs and benefits.

Semiannual reporting might not help big established companies, but it could help the most innovative companies in our economy by encouraging them to allocate more capital to risky, innovative projects. This could provide a big boost for the long-term health of the US economy.

Haresh Sapra is the Leon Carroll Marshall Professor of Accounting at Chicago Booth.

Frank Gigler, Chandra Kanodia, Haresh Sapra, and Raghu Venugopalan, “How Frequent Financial Reporting Causes Managerial Short-Termism: An Analysis of the Costs and Benefits of Reporting Frequency,” Working paper, April 2013.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.