Worried about outsized executive pay, US regulators crafted rules aimed at driving down compensation. But research suggests the move had the opposite result—more disclosure led to higher executive pay.

The research, by Stanford’s Brandon Gipper, who is a recent Chicago Booth PhD recipient, focuses on rules instituted by the US Securities and Exchange Commission in 2006, when it started requiring companies to include a compensation discussion and analysis section in securities filings. These rules represented a significant step in a steady, decades-long march of disclosure regulations designed “to enhance shareholder oversight and prevent managers from receiving unearned compensation, which could result in lower pay,” writes Gipper.

Companies adopted the 2006 rules on a rolling schedule, based on when their fiscal years ended. Then the compensation-disclosure requirements were partially eliminated in 2012, as part of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act.

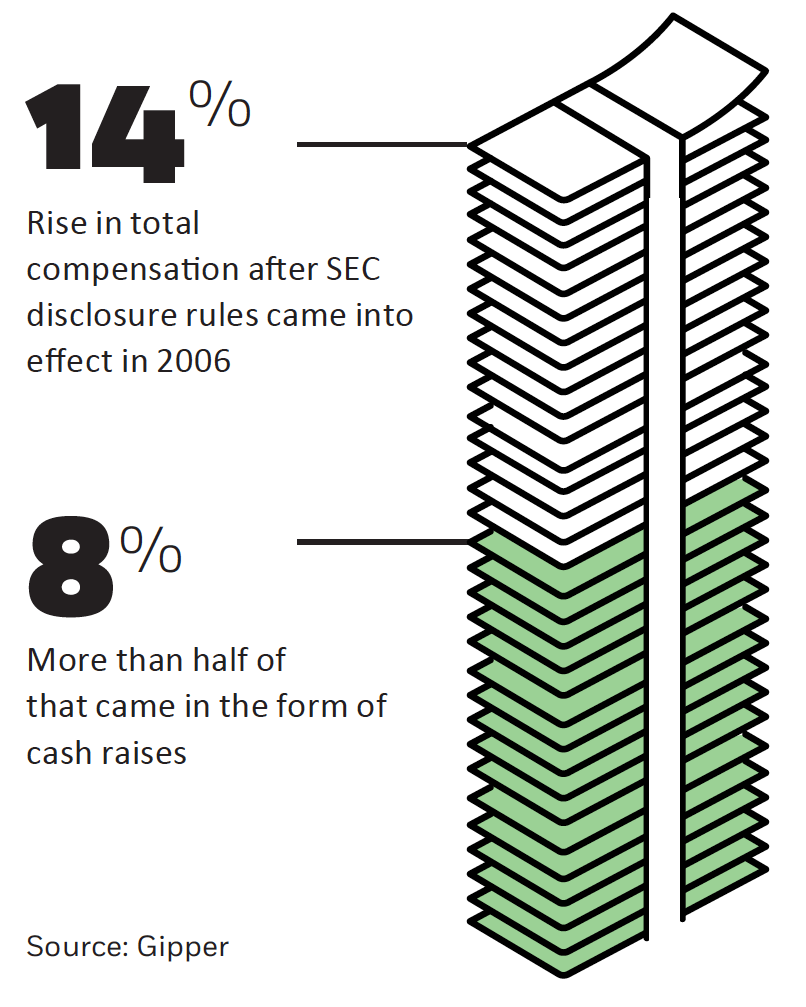

This allowed Gipper to take a clean look at the rules’ effects. He finds, in looking at the first group to adopt the rules (companies whose fiscal years ended in December), total compensation rose by 14 percent after the regulations were instituted. A big part of that increase came in the form of cash raises, which represented more than half—8 percentage points—of the increase. The average manager’s cash pay rose by $60,000.

The main beneficiaries of raises included managers who had been in executive positions for a short period of time, less than four years, along with those who worked for smaller companies and in industries where pay varied more overall, Gipper’s analysis indicates.

Compensation disclosures have had their intended effects in the public sector. Princeton’s Alexandre Mas finds that when cities were forced to disclose more about city managers’ salaries, populist outcry forced pay down 8 percent.

But Gipper has a theory about why compensation disclosures had the opposite effect in a corporate context. When companies published the incentive structures and realized performance of executives, they made it easier for headhunters to match executives with hiring firms and for executives to advocate for raises. For shareholders, disclosure produced an unintended consequence that may be costly.

- Brandon Gipper, “Assessing the Effects of Mandated Compensation Disclosures,” Working paper, June 2016.

- Alexandre Mas, “Does Transparency Lead to Pay Compression?” Journal of Political Economy, forthcoming.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.