Lenders view family businesses as safer investments during a financial crisis.

- By

- March 02, 2016

- CBR - Economics

Lenders view family businesses as safer investments during a financial crisis.

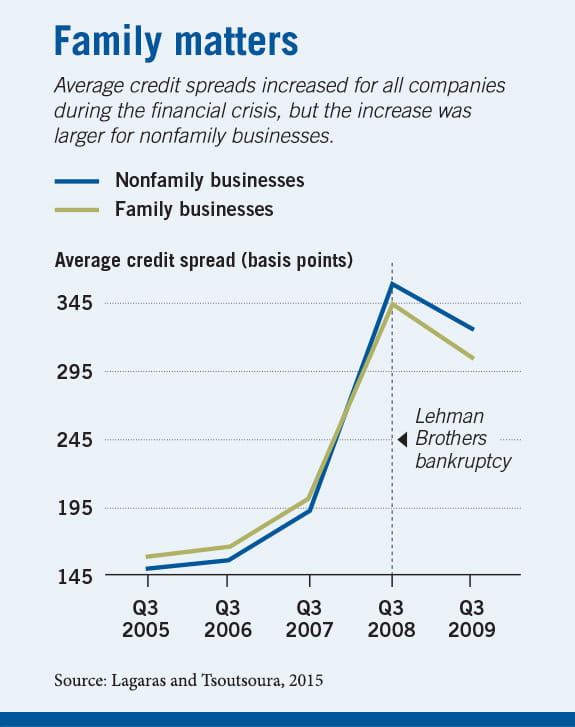

When times are tough, we often look to family. Research suggests lenders do likewise: family-owned businesses paid significantly less for debt than non-family firms when credit was difficult to secure, according to a study of US syndicated business loans between 2004 and 2010. Covenants on many of these cheaper loans during the financial crisis required the founding family to maintain voting power or a minimum ownership stake in the borrowing company, find Spyridon Lagaras of the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign and Chicago Booth’s Margarita Tsoutsoura.

Lagaras and Tsoutsoura provide novel evidence that lenders viewed family businesses as safer investments during the 2007–10 financial crisis. The study focuses on syndicated loans—those made by a group of lenders to fund a particular company or project—involving Lehman Brothers before its 2008 collapse. It follows the credit-spread changes for the borrowers as they replaced the Lehman component of their debt with new loans or increased debt from other institutions.

The researchers find that around the time of the Lehman collapse, nonfamily firms experienced significantly higher rises in borrowing costs than family firms. The increase in loan spreads around the Lehman crisis was at least 24 points lower for family firms, and the differences grew with exposure to the crisis. Specifically, in firms that were highly exposed to the Lehman collapse, the spreads on loans were at least 73 basis points lower for family-owned firms. The differences are sizable given that the mean spread during the crisis was 344 basis points.

Family firms in which a family member acted as a chief executive received the most favorable loan rates, according to the researchers, who also show that loan covenants in 17 percent of the family-business loans demanded that the founding family maintain a minimum percentage of ownership or voting power.

There is no evidence that nonfamily firms had a harder time accessing capital during the crisis, or that the length of loans between the two groups differed, but family firms appeared to receive higher loan amounts, the researchers find.

Spyridon Lagaras and Margarita Tsoutsoura, “Family Control and the Cost of Debt: Evidence from the Great Recession,” Working paper, June 2015.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.