When Social Networks Go Astray

Most of the time, developing and mining a network is a smart move. But avid networker, beware: these social networks have a dark side.

When Social Networks Go AstrayWhen Aldo Zucaro wanted to boost his company’s revenue, he turned to a division that had become entrenched in its ways: the sales team.

Zucaro, senior director of commercial strategy at contact-lens manufacturer CooperVision, knew the company had long tracked traditional sales metrics and used them to reward team members for closing deals. But that, along with on-the-job sales training the company provided, wasn’t enough to ensure employees stayed motivated to work hard after a deal closed. Their sales efforts would often rise and drop with each sales cycle, rather than producing a steady stream of sales throughout the year.

To tame the highs and lows, Zucaro used findings from research conducted by Chicago Booth’s Sanjog Misra and Stanford’s Harikesh S. Nair to measure and incentivize an attribute that’s notoriously difficult to quantify in a corporate setting: effort.

“I compensate on effort, and I believe that ultimately pays off,” says Zucaro.

On the basis of Misra and Nair’s research, Zucaro and CooperVision began running algorithmic analyses of employees’ performance data to quantify the effort they invested in their work. Zucaro then set effort-based incentives using the results of the analysis. Though he’s reticent to discuss specifics of the company’s new strategy, Zucaro says that ultimately, understanding how to appeal to his sales team by providing the optimal incentives “makes the process of selling cheaper.” The new analysis is a supplement, rather than a replacement, for the traditional sales tracking CooperVision was already doing—and, Zucaro says, the behind-the-scenes nature of the analysis makes it simple to integrate into the sales force. Since CooperVision began optimizing incentives for effort, its sales growth has exceeded market-average sales growth in many regions around the world.

Companies have embraced big-data analysis in many areas of business, but largely left their sales teams alone. In the past, optimizing a sales force “wasn’t based on data and analytics,” says Misra. Instead, research was largely theoretical. What tracking was done at the company level tended to focus only on the end result of the sales process. That is perhaps in part because figuring out how to analyze a traditionally opaque part of the organization, where employees often come and go independently, has been a challenge. But the challenge is lessening, and the benefits to companies willing to engage in analytics are significant.

In the past five years, researchers including Misra, Nair, and Chicago Booth’s Øystein Daljord have demonstrated the importance of using existing company data to track the efficacy of the sales process and predict productivity.

Their findings suggest that, while there may still be a place for traditional resources such as sales training, executives can complement them with sophisticated analyses that can tweak employee compensation structures or create new screening tools for the HR department. Even when improvements are incremental, the scale of some sales forces means small changes can make a big difference.

“In sales, each [employee] is contributing a little bit, and it’s easy to forget that they are a critical element,” says Misra. “If you can improve the performance of each of these [employees], it adds up to quite a bit.”

The research suggests four ways data analysis can help fine-tune sales teams:

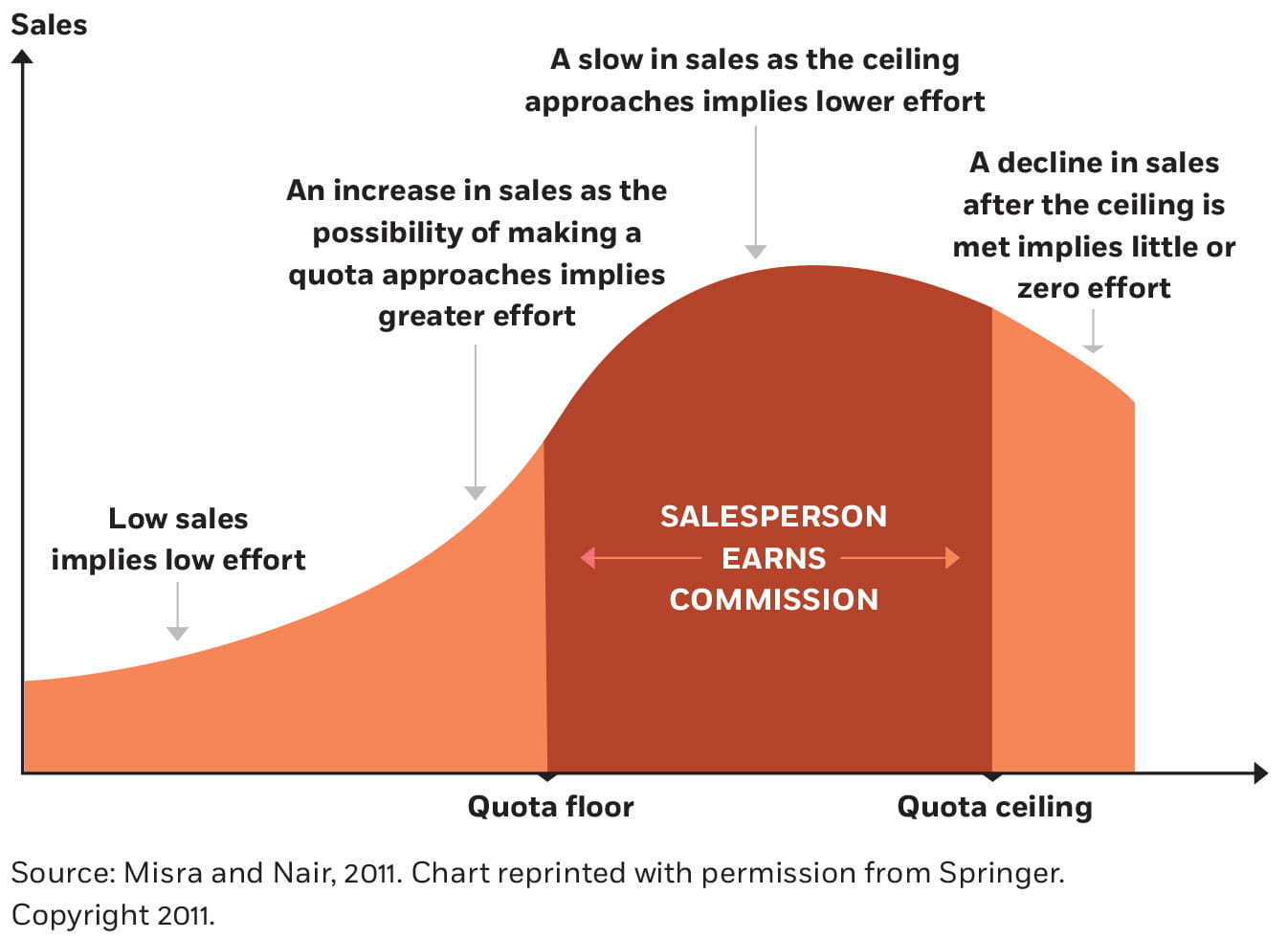

When Misra and Nair worked with a Fortune 500 company to optimize compensation for the 82 sales agents the team studied over three years, they and their fellow researchers observed that the presence of quotas and compensation ceilings actually induced salespeople to be less effective during certain periods of the year. As employees neared the end of a sales period, those who were too far from their quota or too near their ceiling had little incentive to be productive until the next sales period began. The effect was so reliable that the researchers could accurately predict a salesperson’s sales for the remainder of a quarter based on how far she was from her quota or ceiling. “How far away from quota you are seems to affect sales,” says Misra, though he adds that some quotas can work as intended.

To test their analysis, the researchers suggested a new compensation structure, which focused less on quotas, and which the company put into practice with some modifications. The new approach to incentives led to a 9 percent improvement in overall revenues, which was equivalent to $12 million in incremental revenues annually.

Trying times

In some cases, sales quotas and ceilings can diminish incentives for salespeople to exert too much effort—for instance, when they're too far from their quota or too near their ceiling.

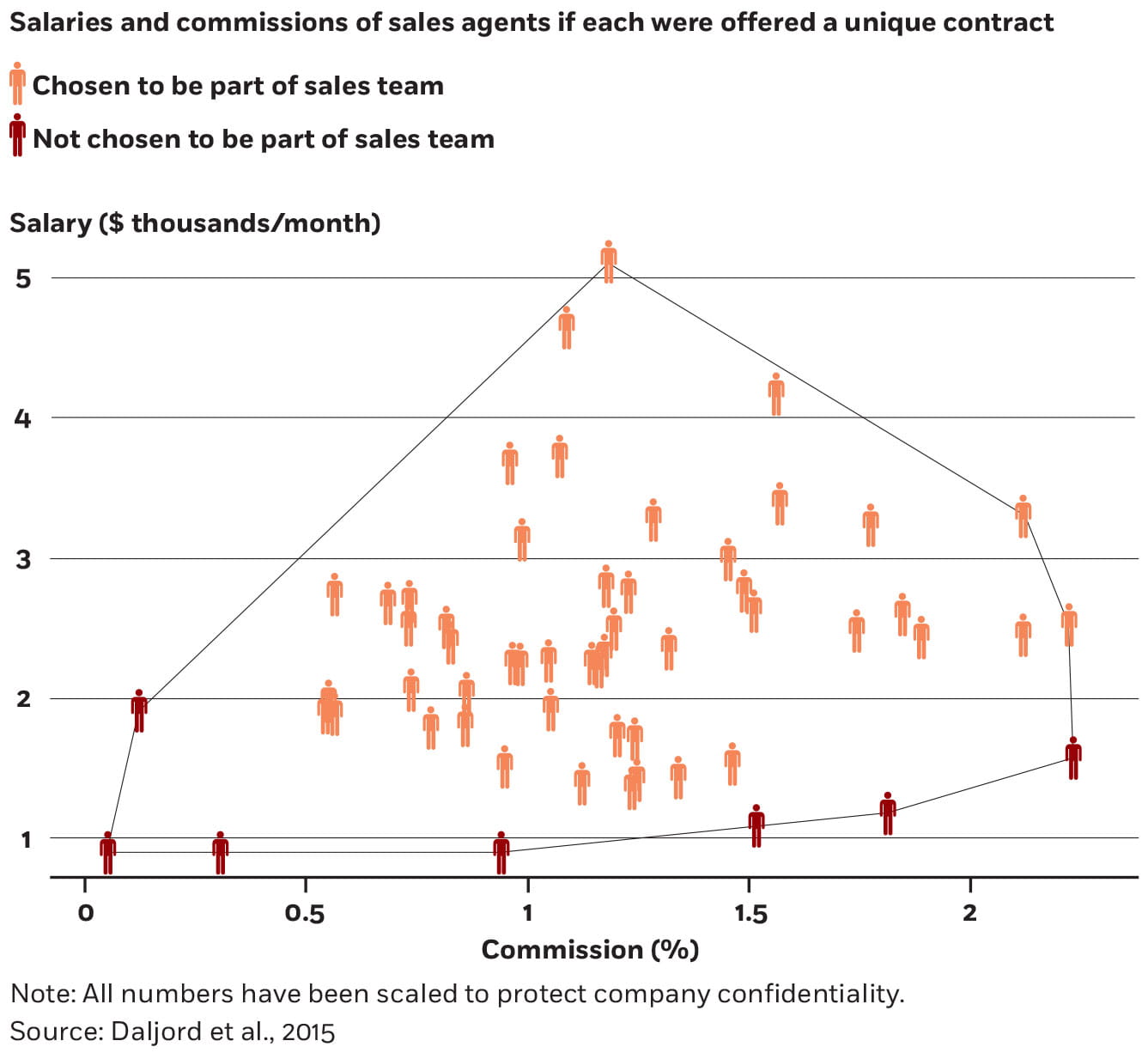

Though many executives would shudder at the difficult task of tweaking incentive structures for every individual, research by Daljord, Misra, and Nair indicates that using different mixes of salary and commission to cater to degrees of risk aversion, productivity, and efficiency can aid in motivation. “Something is lost by the fact that there’s one incentive for everyone,” according to the researchers.

The research indicates how companies can create an individual compensation model for each employee based on an algorithm that uses the employee’s historical performance data to simulate how she would respond to various incentive types. Though it’s complex, the algorithm can take data that already exist and run in the background of day-to-day operations.

The right framework can make it more difficult for incentives to distort employee behavior (for example, working solely to close the sale versus shaping a long-term relationship) or for employees to take advantage of ineffective commission schemes that fail to create long-term buy-in. Furthermore, understanding how incentives affect employees can help companies objectively measure their employees’ effort without tracking their every move. “Even if you don’t see effort, what you can show is that they are impacted by an incentive structure,” Misra says. Not all incentives are financial, he points out; some employees may derive benefit from simply being recognized by their peers.

Because incentives affect people differently, there’s some advantage in avoiding sales reps whose motivations are unlike any of their peers. Instead, it may be more practical to hire employees who have common goals, or group the sales agents according to common preferences, says Daljord. He worked with Nair (his former Stanford advisor) and Misra to show that even when companies opt not to completely individualize compensation structures, hiring employees who share similar tendencies toward incentives can be nearly as effective.

For example, younger employees without a family may perform well with a low salary and lots of performance incentives, whereas for employees with young children, it may be more important to know that they can bring home a certain paycheck every month. Daljord explains that designing different incentive plans for each group isn’t intended to make one group perform better than the other; rather it’s done because when the same incentive structure is implemented identically across all employees, none of the groups performs as well as it could with individualized incentives. Therefore, employers who want to avoid varying their incentive plans should try to build teams who are similarly motivated to begin with, and tailor incentives to that single homogeneous group.

Rather than hiring a headhunter to fill out an existing sales force, using data analytics in the hiring process can yield an applicant who best fits the existing compensation structure, says Misra, which in turn can maximize team productivity. “You never think of HR as being one of the drivers of sales,” he says, but recruiters can make an important contribution to aligning incentives.

During the hiring process, HR can use analytics to help understand how a sales agent will respond to various types of incentives. Hiring a pool of sales employees all motivated by the same things can cut down on the need for constant performance management, Misra adds. “You have these win-win situations that are possible,” he says. “When sales people are happier because of their compensation results, they put in more effort and create more sales.”

“How you pay people matters, and if you want to increase sales, optimize how you pay people.”

Choose wisely

Companies can create near-optimal compensation structures by hiring sales agents who are motivated by a similar mix of salary and commission, research suggests.

With many sales employees now working remotely, managers need a way to nonintrusively monitor day-to-day practices. Gryphon Networks, a sales intelligence firm in Boston, offers companies an updated “sales intelligence platform” that allows them to track dispersed sales teams, says the company’s senior vice-president, Eric Esfahanian. Gryphon helps corporate sales managers understand their employees’ daily activities—whether or not they make a sale—by offering speech analysis of client communications. The speech data are converted into a simple visual dashboard allowing middle managers to digest them at a glance, Esfahanian says.

Gryphon’s tool uses big data to provide insight into a range of performance areas. For example, companies can track the average number of dials it takes to set an appointment or the common responses a rep gets to a specific pitch. While many of these metrics have long been part of a call center’s capabilities, they were unavailable to sales agents working in the field. When the sales force is out of the office, “even the simplest measurement is incredibly difficult to track,” he says.

Researchers have also turned to other multimedia sources of sales data. Misra, along with Aditya Jain of Baruch College and Nils Rudi from INSEAD, used in-store video recordings from eight outlets belonging to a Middle East–based cosmetics chain to understand how salespeople’s behavior affects purchases. The videos were coded with interaction links for salesperson-to-customer conversations and eyeball links for customers who scanned the shelves for products. Shoppers were also categorized in terms of gender, age, and attire to look for sales patterns. The data helped show the importance of sales assistance in encouraging customers to linger at the store, searching through products and ultimately spending more money.

Some managers may be reticent to revolutionize how they track their sales leads or hire staff. The sales environment is often fast-paced and cutthroat, and many chief executives would still rather invest in sales-team training than run models on how to alter compensation.

Nonetheless, executives are more likely to use workplace analytics to dig into sales data than they have been in the past, and they’re spending more time in deciding what to do with metrics that have a long run in the background, says Chicago Booth’s Michael Gibbs, who studies management, incentives, and organizational design. “This isn’t something that’s done by IT in some back room anymore,” he says.

Misra points out that unlike psychological theories on sales-force effectiveness, his research is completely quantitative, and he says companies now feel that incorporating analysis into their sales-force compensation structure is “low-hanging fruit” and can quickly help their bottom line. “How you pay people matters,” he says, “and if you want to increase sales, optimize how you pay people.”

Erik W. Charles, vice-president of product marketing for San Jose–based Xactly, a sales performance-management software company, says a sales team’s incentive plan “has a direct impact on their behavior.” Earlier research from Nair and Misra has helped Xactly’s product development team create a tool for comparing and evaluating incentive programs. The tool compiles more than a decade of sales compensation data from hundreds of companies, allowing clients to explore the data across dozens of metrics.

At CooperVision, Zucaro says using the new data-based models for incentivizing employees has created an opt-out for salespeople not interested in the new approach. Individuals are able to “self-select out of the organization” without management taking a heavy-handed approach to turnover, he says. It’s also changing how the company hires, with recruiters shying away from the “always-be-closing” brand of salesperson. “Hired guns don’t survive in our organization,” says Zucaro. “It’s not how we behave anymore.”

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.