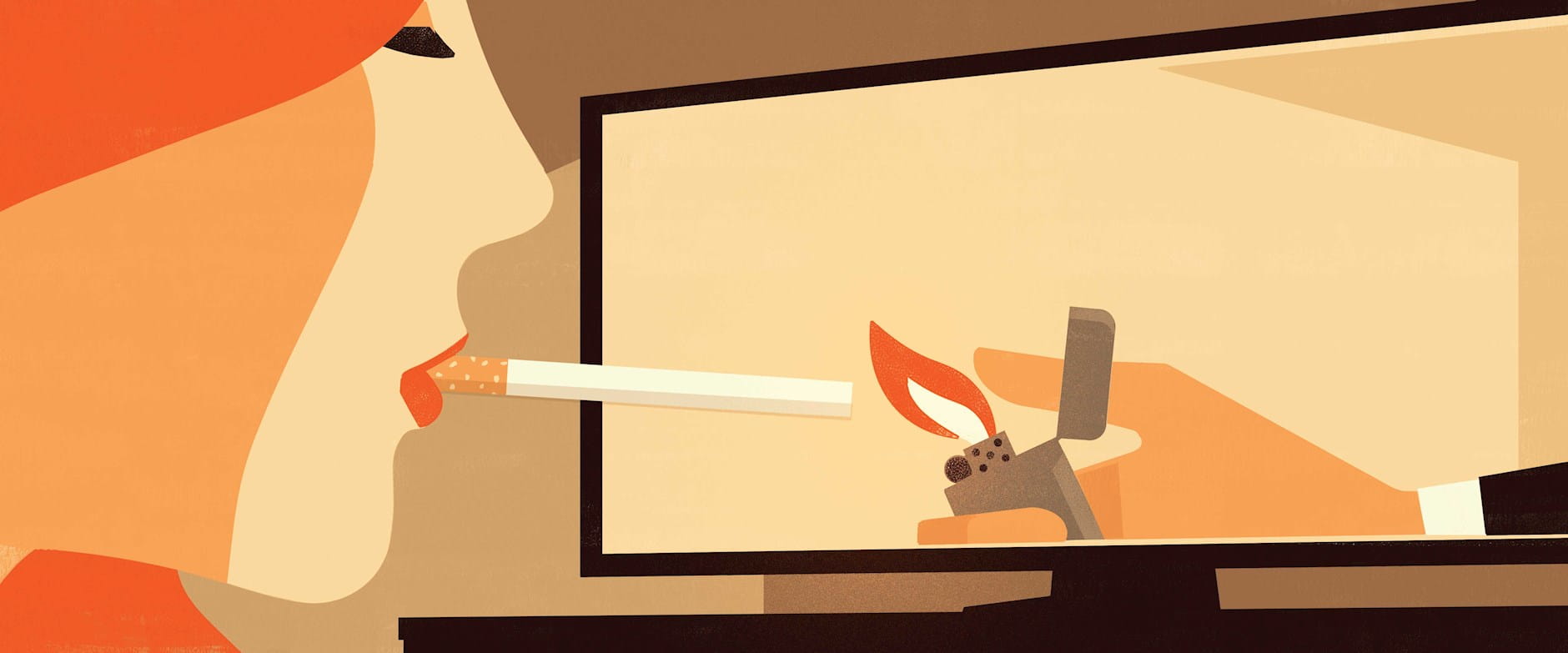

Every time Don Draper lit up a Lucky Strike on Mad Men, the hit series that ran from 2007 to 2015 on AMC, it lent a cool, Madison Avenue vibe to the cigarette brand.

Instances of cigarette product placements such as those in Mad Men boost consumer demand in the United States for cigarettes, according to an analysis by the University of Washington’s Ali Goli and Simha Mummalaneni and Chicago Booth’s Pradeep K. Chintagunta and Sanjay K. Dhar. The researchers’ findings illustrate why product placement on TV and in movies poses a challenge for regulators concerned with keeping cigarette sales from rising.

Roughly 14 percent of adult Americans smoked cigarettes regularly in 2018, down from 42 percent in 1965, according to the American Lung Association. Public-health initiatives discouraging tobacco use have been in place since the 1960s, and a ban on cigarette advertising on TV followed in 1998.

But the rise of streaming services that enable viewers to skip through commercials has increased the popularity of product placement and allowed tobacco companies a new way in. These on-screen moments can be arranged in conjunction with brands, or happen independently of them. Producers like the realistic effect everyday brands lend to a story line, and companies love the exposure. Though it’s illegal in the US for tobacco companies to pay for such appearances in movies and TV shows, unpaid placements, in-kind donations, and payments from foreign affiliates are permitted.

Anti-smoking groups have called for limiting cigarette appearances on TV and in movies, but they and trade groups have for years debated the effect of these appearances on cigarette demand. One back-of-the-envelope estimate from marketing consultants and anti-smoking advocates indicates that Mad Men goosed Lucky Strike sales by 43 percent, a figure that producers have dismissed as speculative.

To find out how much such placement affects retail cigarette sales, the researchers analyzed data on TV-show cigarette product placements, the viewership of the shows, and cigarette sales in 92 market areas from December 2003 to July 2006. They tapped into store-scanner data compiled by market-research company IRI for sales of 15 cigarette brands at more than 2,700 stores in 41 US states, then merged this with all instances of branded cigarette product placement on US network TV.

Advertising data from Nielsen Ad Intel indicated how many people saw the shows featuring product placements. “We needed to see the extent to which placement was viewed by the people in each geographic market,” Chintagunta says.

Finally, the researchers developed a demand model to measure how product placement affected sales. They find a small but positive and statistically significant effect: every 1 percent increase in exposure to cigarette product placement increased sales by 0.02 percent.

Interestingly, product placement by one brand seems to increase sales for the entire cigarette category. “One thing that surprised us—other than that we actually found an effect in the first place—was the extent to which a brand’s own product placement had a similar effect on competitor sales,” Chintagunta says.

This bounce is roughly in line with the effects of TV advertising, the researchers write, and may justify regulating product placement just as strictly. A blanket ban on brand names and logos would lead to a fall in cigarette sales of less than 2 percent, they calculate, but banning all on-screen smoking would reduce sales by up to 7 percent.

“Regulators would benefit from shifting their focus from cigarette brands to TV producers,” the researchers suggest.

Ali Goli, Simha Mummalaneni, Pradeep K. Chintagunta, and Sanjay K. Dhar, “Show and Sell: Studying the Effects of Branded Cigarette Product Placement in TV Shows in Cigarette Sales,” Working paper, February 2022.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.