Why Donors Prefer a Way Out to a Fuzzy Feeling

- By

- December 01, 2015

- CBR - Behavioral Science

In attempts to improve their fundraising, charities will often send appeal letters to potential donors that include emotionally charged content, such as images and stories of recipients. But research suggests that to increase contributions, nonprofits can do more than appeal to pity—they can promise to never contact the donor again.

In a working paper published as part of a research series on charitable giving by the Science of Philanthropy Initiative, Chicago Booth PhD and MBA graduate Amee Kamdar, University of Chicago’s Steven D. Levitt and John A. List, Brian Mullaney of WonderWork, and Chicago Booth’s Chad Syverson analyze the results of a mail campaign by Smile Train, the world’s largest cleft charity. On some of the envelopes in the campaign, the researchers included a frank proposition: “Make one gift and we’ll never ask for another donation again.” They find that this “once and done” strategy increased total contributions by nearly 50 percent.

Mailings went out in five waves to some 830,000 individuals between April 2008 and September 2009, split between treatment (once and done) and control (regular mailer) groups. The once-and-done households who made a donation could then check a box to opt out of any future solicitations, another box to be contacted twice a year, or a third box to receive more-frequent communication.

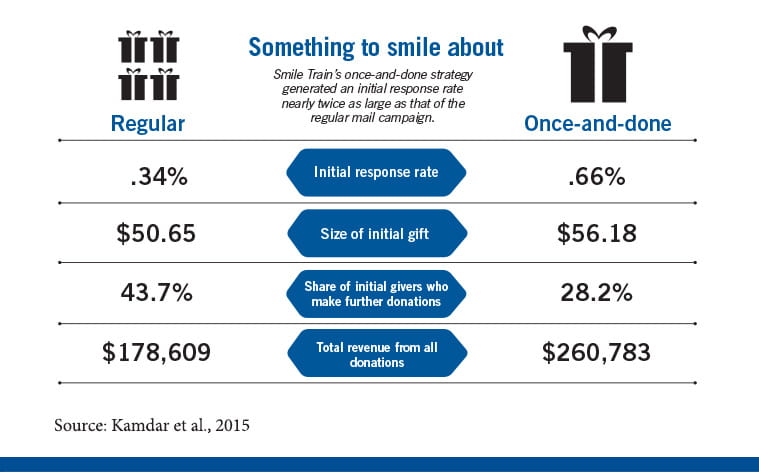

Although 38 percent of the donors in the once-and-done group selected the “do not mail” option, that group had so many more initial donations (0.66 percent versus 0.34 percent in the control group) that total subsequent donations between the two groups were comparable. Between initial and follow-up donations, the treatment group generated a total of $260,783 compared to $178,609 for the regular mailings.

The results defy the conventional notions that the largesse of donors is purely altruistic or egoistic. The researchers argue that withholding future opportunities to help children with cleft problems conflicts with the empathic motivation for giving, as well as with the idea that gifts are motivated by a “warm glow” feeling they bestow upon the giver. “If it feels good to give,” they ask, “why would donations rise when we link giving now to a restriction of future opportunities to give? And furthermore, why would nearly 40 percent of the donors, in a warm glow world, opt not to receive future mailings?”

The data are more consistent with a popular behavioral theory known as social pressure avoidance, which posits that charitable solicitations impose an unpleasant feeling of social pressure on the recipient. The theory explains why so many people sought to escape from future requests by making a single donation. But the average initial donation in the treatment group was 11 percent larger than in the control group, whereas one would expect that those simply seeking to avoid pressure would give less, on average, than those genuinely committed to the cause.

The authors conclude that the model best matching the observed results is one of “short-lived reciprocity”: the charity offers to surrender its right to future solicitation, and in return, recipients reward the charity with funds. But donors from the treatment group were less likely to make subsequent gifts than donors from the control group, which suggests the shelf life of that reciprocity doesn’t extend beyond the first donation.

Amee Kamdar, Steven D. Levitt, John A. List, Brian Mullaney, and Chad Syverson, “Once and Done: Leveraging Behavioral Economics to Increase Charitable Contributions,” Working paper, January 2015.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.