Foreclosures soared during the Great Recession as a pronounced boom-bust housing market left many homeowners underwater. But while some people walked away from their loans because of negative equity, the vast majority of US homeowners who defaulted between 2008 and 2015 encountered cash-flow issues due to life events—such as job loss, divorce, injury, or illness.

That’s according to research by University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy’s Peter Ganong and Chicago Booth’s Pascal Noel. By their calculations, 94 percent of the defaults can be explained by negative life events. This suggests cash flow plays a far bigger role in people losing their homes than previously thought.

Economists have three main theories as to why people default on home loans. There’s cash-flow default, triggered by a life event such as the homeowner losing a job and no longer being able to afford the monthly payment. Then there’s strategic default, which is a function of the house’s value, not the borrower’s financial situation. The third theory is a double-trigger default, a combination of the two.

Previous estimates attributed 30–70 percent of foreclosures during the Great Recession to strategic default because of negative home equity. But Ganong and Noel find that only 6 percent of underwater defaults were caused strictly by negative equity. That’s a huge departure from these earlier studies, probably because of data limitations and measurement error, the researchers suggest.

What Ganong and Noel did differently was to examine mortgage-servicing records and related checking-account data. Linking bank accounts and mortgages—in this case, of 3.2 million Chase customers—was key to demonstrating actual income losses. It enabled the researchers to untangle the role of negative life events from that of negative equity.

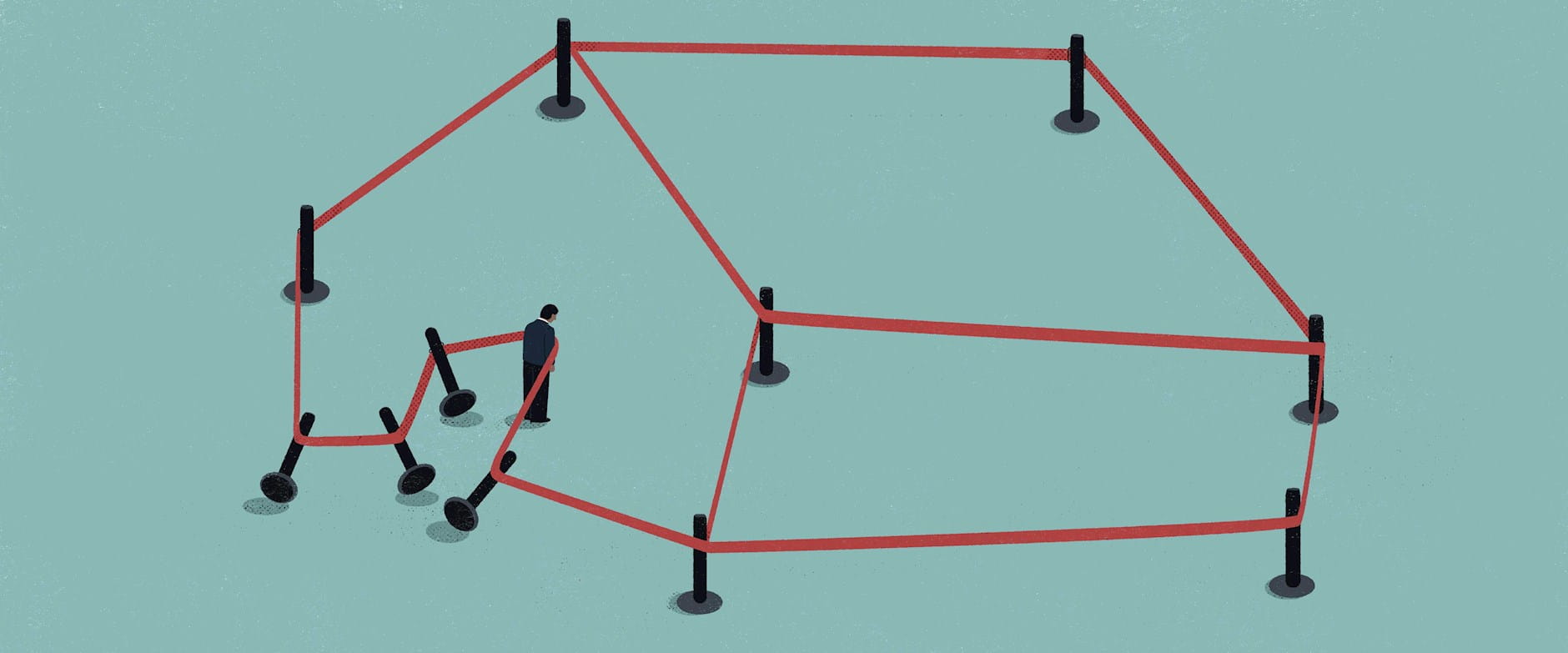

No cash to pay the bill

When borrowers defaulted on underwater mortgages (in which principal owed outstripped home value), it was almost always triggered by a life event such as an illness or divorce.

Mortgage-servicing data do not contain information on current income or possible triggering life events, so previous research used out-of-date information, such as a household’s payment-to-income ratio at the time of mortgage origination, not when the payments stopped coming. Ganong and Noel looked into information on household financial circumstances at the time of default—defined as missing three mortgage payments—via the linked checking-account data.

To form a sort of baseline, they separated out defaulting homeowners with positive equity. Reasoning that these borrowers who were holding above-water mortgages couldn’t default because of negative equity, the researchers assumed they must be defaulting because of an adverse life event. They used income patterns as a benchmark for cash-flow defaults driven by negative life events, and sure enough, they find that for above-water homeowners, incomes declined sharply in the months leading up to a default.

They then find that underwater homeowners experienced similar income declines before defaulting. The drop in income leading up to default was almost identical for both groups, meaning that neither had enough cash available to cover a mortgage payment.

To separate out the double-trigger defaults, the researchers examined the impact of negative equity on default. They find that eliminating negative equity would prevent only 30 percent of defaults, leaving 70 percent of them entirely attributable to cash-flow issues. Twenty-four percent of defaults were a combination of the two. This held for homeowners with different levels of income and types of mortgages as well as across time periods and geography.

For policy makers, it matters why people default. Forgiveness of principal is costly and addresses only defaults related to negative equity. What could be more beneficial, according to the researchers, would be temporary payment reductions. Considering that the vast majority of defaults follow negative life events that could resolve themselves over a couple years, lowering payments temporarily could help banks recoup their money long term and help people keep their homes.

Peter Ganong and Pascal Noel, “Why Do Borrowers Default on Mortgages?” Quarterly Journal of Economics, October 2022.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.