The third installment of our quarterly Business Practice feature asked readers to imagine having to deliver negative feedback to a subordinate:

You manage a team of analysts at Trend Line, a market-research firm. Their role is to collect data on the restaurant industry and compile them in written reports. The reports are recognized as among the best in the business, in part because they are easy to read. Because of this, you value your analysts as writers as much as researchers.

You hired Stephanie as an analyst about six months ago, and several of her assignments have come due. She has mentioned that it was a joy to write the reports and that she is excited to get feedback from you. But there’s a problem: her prose is awful, almost unreadable. It has problems that go way beyond the stray typo.

This morning, she came by your office and asked how you liked the reports. You hardly knew what to say, so you asked her to come back in the afternoon to talk. She smiled, said yes, and bounced out the door.

What do you say to her when you meet?

Depending on when readers visited the Chicago Booth Review website, they saw either this scenario or an identical one involving Stephanie’s male counterpart, Stephen. Any responses that they subsequently rated were written for the same version of the scenario they read and responded to. Sneaky of us.

Why is this question difficult?

This scenario is a twist on our last Business Practice conundrum, in which participants had to navigate a tricky peer confrontation. Now, you are a manager who needs to give feedback to an underperforming subordinate. Being the boss, for sure, makes this conversation a little easier. But there are other things that make this situation unpleasant, most notably that Stephanie/Stephen is clueless—she/he is expecting accolades. More generally, managers, like all people, may anticipate interpersonal conflict and tend to shy away from such encounters or deliver less harsh feedback than is appropriate. Consequently, many of us are relatively inexperienced at delivering negative feedback. And because we avoid these kinds of situations, there is little opportunity to disconfirm a possibly exaggerated fear of a negative interaction.

Scenario participation

We posted this scenario on December 17, 2018, and closed the survey on January 10, 2019. We received 102 separate responses (55 for Stephanie and 47 for Stephen), with the responses ranging in length from eight to 397 words, with a median length of 95 words. The responses were rated 982 times. Each response was rated on average nearly 10 times (median: eight), with 81 responses (79 percent of all responses) receiving five or more ratings. (The infrequently rated responses were submitted late in the cycle, close to when the survey was closed.)

Ratings

Responses were rated on a 1 (“Strongly disapprove”) to 7 (“Strongly approve”) scale. A histogram of all ratings is shown below.

The mean rating is 4.01, almost exactly in the middle of the scale. As in the previous two installments of Business Practice, the difficult scenario made it nearly impossible to produce a response that everyone found outstanding.

We next turn to the average ratings of each response submitted. The following analysis is restricted to the 81 responses with five or more ratings, with the average rating for each of those responses plotted on the histogram below. The overall average rating is 3.89, with responses ranging from the worst rated (1) to the best rated (5.44). As has been the case in the past, many responses were viewed as reasonable, but there were no responses that were universally seen as outstanding.

Just over half of responses (57 percent) came from men, but for the third straight time, female responses performed better (4.28 average rating) than male responses (4 average rating). Among the 13.7 percent of responses that came from participants who used a ChicagoBooth.edu email address, the average rating (4.47) was also well above average.

To give you a sense of the range of ratings, I’ve listed a few responses spanning the range from unfavorably rated (5 percent, 10 percent, and 25 percent in the distribution, meaning that 95 percent, 90 percent, and 75 percent of responses are rated better), to average (50 percent in the distribution), and favorably rated (75 percent, 90 percent, and 95 percent in the distribution). All of these responses had five or more ratings. (All responses included in this article were subject to light editing for grammar and style.)

5 percent response

Answer: “Appear to be in a tough spot, and ask: ‘How can I help you get the prose writing to the level typically expected?’”

Average rating: 2.11

10 percent response

Answer: “As an analyst, you should understand that your essential job is to report [on] complicated business with concise and clear language. I don’t doubt your ability in analyzing situations, and I like your passion for the project. However, you have to ensure your writing is well organized in order to make the progress more efficient.

“Next time, come back with better formatting.”

Average rating: 2.67

25 percent response

Answer: “Stephanie, I admire your energy and enthusiasm. I also recognize you enjoy your job. With that, I am keen to see you succeed in this role.

“Looking at your past reports, I have identified some room for improvement to bring your work quality to a higher level. One of which is to identify who your readers are and how they would compare your writing with other writers. Some feedback I’ve received is in the quality of your writing. So please take the time to reflect what you can do to improve in that space, and let’s discuss again if it can work.

“Please take this as positive feedback and [understand] that it is in my interest that you succeed.”

Average rating: 3.52

50 percent response

Answer: “Stephanie, in giving you feedback, I hope to be able to contribute to your professional growth. And therefore, it is in your interest that I give you honest and actionable feedback. If there is any aspect that you would want to understand better, I would be more than happy to spend more time with you on it.

“First, let me tell you what we really like about you. It is a joy to see your enthusiasm and commitment to work. It is infectious, and creates a truly positive work environment. We would like to thank you for all your contributions.

“Let us now talk about potential areas for development. Let me tell you what we expect from newly hired analysts at the firm. We are the gold standard in market research. And therefore, we expect nothing less than superlative output. While there is nothing lacking in terms of your work ethic, you do need to work on your writing. Our customers value the clarity of expression that we bring to our reports. This allows them to understand and internalize our research far more quickly than in the case of our competitors’ reports. It is what keeps them coming back to us. If we cannot deliver that to them, we are essentially failing them.

“I would suggest that you read some of the reports that our senior analysts have produced, and then revisit some of the reports that you have written over the past six months. It would help you understand where you might be lacking. And then you can start working upon yourself to improve. Let us know how we can help you develop, and we would certainly provide you with the resources that you need to succeed.

“If, however, you realize that you have hit a block, it might well be a sign that this is perhaps not the right firm or the right role for you. In which case, we could always look at other opportunities for you within the firm, or help you identify the right opportunities for you outside the firm. Personally, I would really like to see you succeed, and I am willing to do all I can to enable you to. I truly hope this feedback will help you, through introspection, to improve. I would be happy to answer any questions that you might have for me.”

Average rating: 4.33

75 percent response

Answer: “Thank you for all the hard work you did on these reports, and for your enthusiasm and passion. I want to be completely honest with you. These are really not written in the style that our readers have come to expect. They differ from that expectation in the following ways: _____ [list out the flaws in a succinct, nonjudgmental manner]. I know you’re still new in your role here, and it’s clear to me that we have not given you adequate support and direction for these assignments. I appreciate that you gave it your best effort, and I want to give you the opportunity to collaborate with one of our senior analysts to rework these. I would be happy to give you feedback on a new draft within the week, with a final deadline of _____ [insert reasonable period of time given final deadlines for publication]. I wish I could give you more time, but we do have to get these out the door soon. [Smile warmly.] Thank you again. Our senior analyst, _____ [insert name of senior analyst that is about to complain about mentorship duties], will stop by your desk in a bit.”

Average rating: 4.71

90 percent response

Answer: “I’d tell him I am excited to work with him and really appreciate his enthusiasm for the work. I’d then start asking questions around what his writing process entails, if he had taken any time to look at previous reports for guidance on our organizational style and approach and if he shared his work with colleagues to get their feedback and guidance, since they would have experience in what our typical reports focused on and our style. I’d let him know his drafts were a good start, but there are some areas I think need to be reworked, and using past reports, discuss some ideas on how he should go back and rework his submissions. I’d also offer either myself or others (with their approval) as support as he reworks his draft and schedule time for us to touch base prior to a new deadline for a new submission for my review.”

Average rating: 5.08

95 percent response

Answer: “Stephanie, I really appreciate the energy you bring to the team, and I’m pleased that you’re so enthusiastic about the work we’re doing. Further, you’re doing an excellent job of _____ [find something praiseworthy in her performance—maybe the analytical aspect of her job].

“But I do have some serious concerns about the quality of the prose in your reports, and I think it’s good you’ve sought out feedback early in your career here. As you know, the readability of our work is one of the things that sets Trend Line apart, so it’s crucial that we address these problems now. I know that you have the desire to excel here, so let’s look at where things are going off the rails a little in your reports and see how we can get them back on track. Then let’s set up regular meetings to review your work in progress, address any questions you might have, and look at ways you can continue to improve.”

Average rating: 5.18

Some clear patterns emerge. The first two responses are direct and lacking in constructive feedback. The remaining responses vary in what elements are included and how and when these elements are delivered, but they tend to be critical but constructive, at the same time maintaining some positivity.

I have coded the responses for a few elements:

- “Sandwich” feedback: constructive feedback, sandwiched between positive comments at the beginning and the end

- Mentorship offer

- Specific help on writing

- Mentions of the employee’s enthusiasm and energy

- General praise of the employee’s nonwriting skills

- Negative and condescending tone

- Questions about why this employee was hired and/or suggestions that firing might be possible

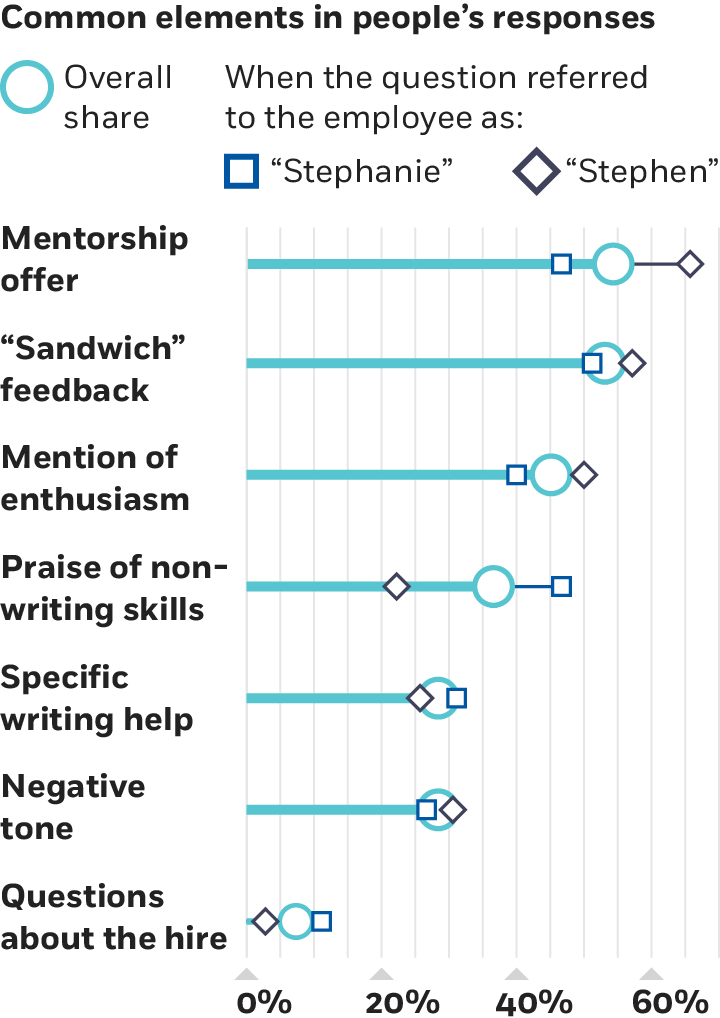

The graph below shows the frequency with which each response element is used. You will also see differences in how Stephanie and Stephen are treated. (More on that later.)

By running a regression, we can see how each of these components contribute to the average rating of a response. Acknowledging the employee’s enthusiasm and praising skills had a modest positive effect on the rating of a response. In contrast, the sandwich technique, a particular manner of recognizing the employee’s positive characteristics, had a negligible effect on evaluations. An offer to mentor was the biggest contributor to a positive evaluation, while specific suggestions on writing had essentially no effect. Not surprisingly, negative and condescending language was not viewed positively, nor were threats of termination or questions about why the employee was hired in the first place.

Gender-based differences

Nothing so far explicitly considers whether our employee was named Stephanie or Stephen. Although the average rating of responses was not significantly different (Stephanie: 4.03; Stephen: 3.93), there were several aspects of the responses that varied dramatically by gender. The graph above showing how frequently response elements were used reveals that these elements were employed differentially for Stephanie and Stephen.

Why Business Practice?

Words matter. The first year I taught negotiation, I ran into one of my students in the cafeteria. After a few minutes of small talk, she asked me: “What qualifies you to teach negotiation?” Ouch. I believe that she meant to ask: “Negotiation is an interesting class to teach. How did you come about teaching this class?” Words matter.

Preparation matters too. The “what qualifies you” question is one I did not anticipate, especially in my early days as a professor. But years later, I’ve heard many questions—straightforward, incisive and cutting, sincere but naive, tricky and lined with booby traps, difficult to answer, and just plain bizarre.

Business Practice is a quarterly series designed to help you better deal with challenging conversations. It is a partnership between Chicago Booth Review and the Harry L. Davis Center for Leadership, of which I am the faculty director.

We built these elements into Business Practice:

- You prepare a response to a challenging conversation.

- You are then invited to see and rate responses that were put forth by others.

- After the question is closed, you get feedback about how your response was judged by others.

The inspiration for this series comes from my friend and former PhD student, Cade Massey, a Booth graduate who is now a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. Over the years, Cade and I, like all negotiation teachers, have been bombarded by requests for advice on how to deal with difficult negotiation situations. We do our best to answer these questions with students one-on-one. Why not be more efficient and systematic and discuss these in class? And, perhaps more important, why not help students learn from these encounters and come up with a better answer for themselves? So, in my class, I have students script responses to five difficult negotiation questions. “Scripts,” as I call this part of class, has consistently been one of the most popular elements of my Advanced Negotiations course.

Students in my negotiations class learn by seeing the wide range of student responses—some very different in style and strategy, some identical in intention yet executed very differently. Students also rate responses in real time, giving letter grades ranging from A to F. Students are often shocked to see the broad range of ratings for the same response—it is not uncommon for a response to elicit an impassioned A and an equally vociferous D.

That’s why the crowdsourcing of ratings in Business Practice is especially valuable. The readers of Chicago Booth Review are a sophisticated bunch. They reflect a wide range of perspectives, interpersonal styles, experiences, and culture. Tons of research in social psychology has documented our tendency to be egocentric in our predictions: I choose a response because it is appealing to me, and hence I expect it to be effective with others, some of whom may think like me but many of whom will not. Learning to step out of our shoes and into the shoes of the many others we may encounter is an extraordinarily useful skill.

Needless to say, difficult situations are not confined to negotiation; they are part of daily organizational life. That’s the impetus for Business Practice. We look forward to helping you prepare for the difficult situations in your own professional life—just as you, through your feedback, will help others prepare for theirs.

Earlier, I indicated that offers of mentorship were seen very positively. Unfortunately, these offers weren’t doled out equally: 65.7 percent of responses to Stephen had mentorship offers, compared to 46.7 percent of responses to Stephanie.

There was a more dramatic effect on the other tail of responses. A small number of responses questioned why the employee was hired or suggested that the employee was on the path to termination. For Stephanie, 11.1 percent of responses questioned her hiring or alluded to a possible firing down the road. That number for Stephen was 2.8 percent.

However, these responses were atypical, obscuring a second asymmetry: Stephanie was more likely to be praised (46.7 percent) than Stephen (22.2 percent). This doesn’t sound bad in terms of a gender bias against women—after all, the presence of praise contributed positively to the evaluation of a response. On the other hand, if praise results from a mistaken belief that women can’t handle the truth, then one unfortunate implication is that women may very well receive more impoverished and less actionable feedback than men.

Top-rated responses

Now for the top three responses. I’ve listed names and backgrounds when I’ve gotten permission to do so.

#3

Response: “Give her the sandwich. Good-bad-good feedback.

“Start with good: love the enthusiasm, and it shows you love your job.

“Then the bad: what makes Trend Line an industry leader is readability. Your recent assignments have fallen short of this. Ask her to critique and walk through. Anything I can help with? Everything OK outside of the office?

Close with good: offer coaching and help to get to expectations.”

Average rating: 5.20

Participant: Kevin

Background: Management consultant

#2

Response: “This situation requires appreciation, but also honesty and reinforced accountability. Assuming Stephen’s content is good, but his delivery needs work, I would sit down with Stephen and tell him exactly that.

“If our team’s research is known to be the best in the business and easy to read, I would ask Stephen to reread his own work and think about how his reports would sound as a reader/consumer and not just an analyst. From here, I would reinforce the soundness of his content, but we would work together to reassess and develop a plan that spells out what is acceptable and how we are going to work together to achieve it. This may include working with Stephen to set up a template, or holding weekly or biweekly one-on-one meetings to really delve into Stephen’s thought process as he is writing his report, so you can reinforce the need to approach the reports in the mind-set of a reader. It’s important that you affirm Stephen’s idea/content as an analyst, but be specific in how he can improve his writing.”

Average rating: 5.29

Participant: Jas

Background: Unknown

#1

Response: “Hi Stephen, thanks for dropping in. I have been going through some of your reports and am so glad to have you on the team. You have generated quite some valuable insights from the restaurant industry data, and I am sure it will be useful for anticipating future trends.

“It is great that you are proactively seeking feedback, and I did want to confess that the quality of prose in those reports does not do any justice to the valuable insights you have come up with.

“Engaging and lucid prose is one of the major reasons our reports are considered valuable, apart from the industry insights. I believe we can easily magnify your impact by reworking the language a little, as the underlying analysis is great.

“I have found a few online learning modules that may be helpful as refresher courses as you begin editing. You could also reach out to our editing team directly for advice. Please let me know if you can think of anything else we can initiate to help resolve this on priority.

“I love your energy and passion to help our customers and am excited to support your progress on this journey.”

Average rating: 5.44

Participant: Divyangana

Background: Unknown

Thanks for these responses. Each of the respondents will receive a Business Practice coffee mug. Display it proudly!

Strategic takeaways

The manager’s role in this scenario is to be honest with the employee about the underperformance but still make the employee feel that success is possible—and maintain or improve the relationship. It’s a difficult line to navigate.

- Mentorship, especially for a new employee, can be a helpful strategy for improving performance. As a side benefit, the high performer you tap as a mentor may find the role motivating.

- Using the cudgel of threatening job security is unlikely to be successful. Although at some point managers do need to make underperformers aware when their jobs are in peril, premature discussion of the prospect of unemployment is bound to be unproductive.

- Needless to say, treating employees differently based on gender is a bad practice. But it can happen unconsciously. Be aware of the implicit associations that may affect your leadership.

George Wu is John P. And Lillian A. Gould Professor of Behavioral Science at Chicago Booth.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.