Want a Lower Phone Bill? Call Congress

- By

- March 01, 2017

- CBR - Economics

US cell-phone customers pay billions of dollars more than some of their European peers, and the difference has a lot to do with government policies, according to research by Purdue University’s Mara Faccio and Chicago Booth’s Luigi Zingales.

Faccio and Zingales examined telecommunications data for 148 countries and find that where government policies promoted competition, consumer costs declined. And despite industry suggestions to the contrary, competition didn’t seem to reduce service quality.

Since governments tightly control the electromagnetic spectrum that transmits cellular traffic, the researchers used the mobile-communications market to investigate the role government can play in creating competitive markets. Analyzing data from the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and the Groupe Speciale Mobile Association, Faccio and Zingales scored countries based on factors their governments can influence, such as phone-number portability, the use of Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP), and foreign entry or ownership in mobile telecommunication companies.

The costs of poor competition

A more competitive mobile-communications market would likely save Americans money without damaging service quality.

Faccio and Zingales, 2017

Governments restricted competition for various reasons, the researchers say. The industry tended to lobby against increased competition, which it portrayed as a drag on profits—and on investing in new or better technologies that could improve service. Governments may restrict the number of companies participating in auctions to maximize the amount of money the state can collect, the researchers conjecture—and governments may want a few, large companies that they can tax highly.

The findings indicate that markets with less competition and higher prices had lower quality services, so “there is no evidence suggesting that a government should tilt the rules in a noncompetitive dimension to enhance the quality of services,” the researchers note. They also find that governments with high sales taxes were more supportive of competition, and that spectrum auctions with less competition didn’t generate more money for governments, since more bidders tended to produce higher auction prices.

There is little evidence that political ideology affected regulatory choices, but the more democratic a country, the more likely it was to favor competition, the findings suggest. Of 10 countries that the ITU rated worst for competition, four—Kuwait, Belarus, Swaziland, and Cuba—were considered the most undemocratic by the Center for Systemic Peace. And the 10 countries with the highest procompetition scores were all rated as highly democratic.

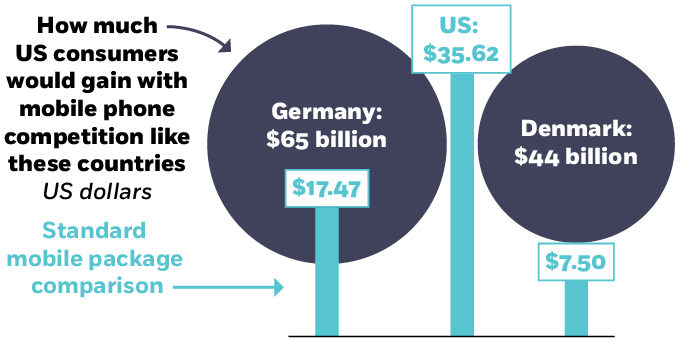

Greater competition can lead to significant savings, the researchers write. Danish and German cell-phone users, who enjoyed significantly more competition than Americans, paid $7.50 and $17.47, respectively, for a standard package of phone calls and SMS messages. That same package cost a US resident $35.62. American consumers would gain $44 billion–$65 billion if the US telecoms market were as competitive as those in Denmark and Germany.

Mara Faccio and Luigi Zingales, “Political Determinants of Competition in the Mobile Telecommunication Industry,” NBER working paper, January 2017.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.