Voters Care about Tight Races, Not Just the Issues

- By

- August 17, 2017

- CBR - Behavioral Science

It’s long been assumed that polls predicting landslide elections keep voters away—both those backing the presumed winner and those who might have voted for the loser. Now University of Chicago’s Leonardo Bursztyn, University of Munich’s Davide Cantoni, University of Lugano’s Patricia Funk, and University of California at Berkeley’s Noam Yuchtman have data to support that idea.

The researchers studied Swiss federal referenda from 1981 to 1998, a period in which there were no polls, and from 1998 to 2014, when poll data were widely disseminated through newspapers. Looking at voting data during the latter period, from 2,342 municipalities for 280 referenda, the research team finds that when poll data showed a tightening race, more people cast votes.

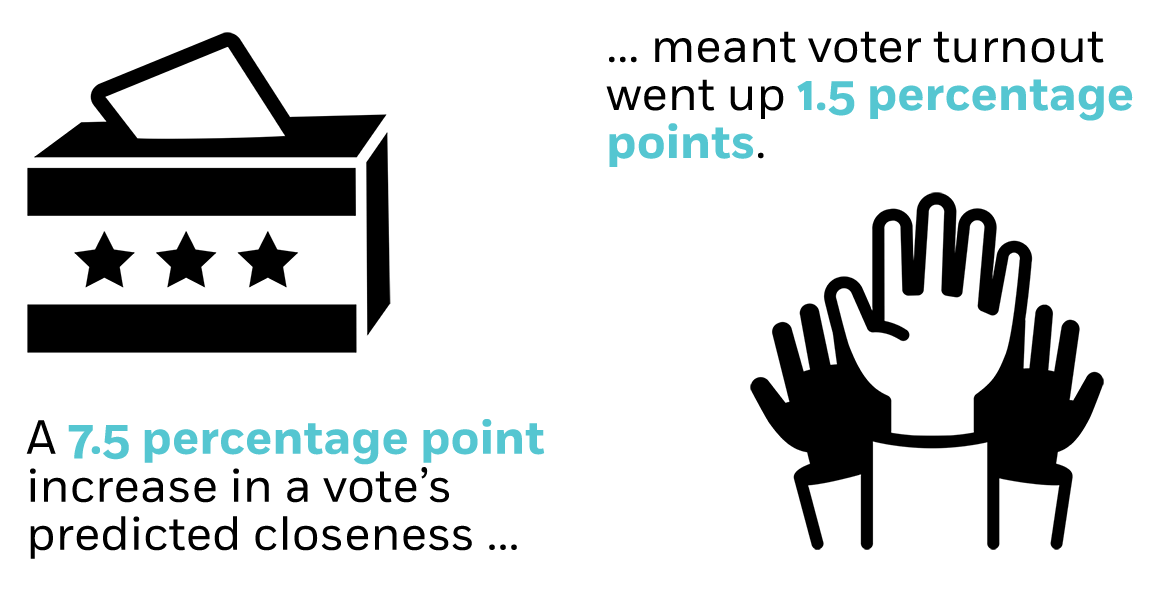

To measure the closeness of the referenda, Bursztyn, Cantoni, Funk, and Yuchtman used the predicted polling percentage of the side that ended up losing the vote: the higher that predicted percentage, the closer voters anticipated the vote would be. The study finds that for the average referendum, all else held equal, an increase in predicted closeness of 7.5 percentage points caused an increase in turnout of 1.5 percentage points. The closer the vote was anticipated to be, the stronger the turnout.

A close election drove more turnout than did political newspaper advertisements. The tightness of races was more significant than the weight voters put on the issues addressed by the various referenda.

It’s difficult to know which election Swiss voters might have believed would be close before 1998, but vote analysis from the 1981–98 period shows a weak relationship between voter turnout and the closeness of the actual vote. Once poll data were introduced in Swiss newspapers, election closeness and turnout were strongly linked.

The researchers hypothesized that if poll closeness spurred voting, they would see a bigger impact on turnout in politically unrepresentative municipalities—places where one party or political ideology dominates. (Perhaps these areas are like echo chambers, wherein sameness lessens voting urgency.) Prior to polling, unrepresentative municipalities had no relationship between turnout and close election results, while politically representative municipalities did, suggesting more-mixed areas supplied informal voting-expectation news. Once polling was introduced, close polls drove higher turnout in politically unrepresentative areas.

“And, in the era with polls, politically unrepresentative municipalities’ relationship between closeness and turnout became statistically indistinguishable from that of politically representative municipalities,” the researchers write.

They add that while this is admittedly speculative, the findings suggest that the closeness of polls could have had an effect on Donald Trump’s victory over Hillary Clinton. Though major polls all suggested Clinton would win, those conducted by more-right-leaning news organizations had the race much closer than those that lean left. It’s possible that Trump supporters saw an opportunity, while some potential Clinton voters were overconfident in a win and stayed home.

Leonardo Bursztyn, Davide Cantoni, Patricia Funk, and Noam Yuchtman, “Polls, the Press, and Political Participation: The Effects of Anticipated Election Closeness on Voter Turnout,” NBER working paper, June 2017.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.