To Treat COVID-19’s Economic Impact, Start by Keeping the Lights On

Minimizing disruptions to workers and businesses will be expensive. It’s worth it.

- By

- March 21, 2020

- CBR - Economics

How should we think about containing the COVID-19 economic crisis?

Christmas lights, when I was a kid, were wired in series. If one light bulb blew, the whole string went dark. My Depression-era parents taught me to fix it by checking each bulb, one-by-one, all one hundred of them. The tree was dark for a long time. But since bulbs were expensive and labor was cheap back then, the prolonged darkness was worth it.

Today, I would do it differently. I would tend toward a costly-but-quick option and replace all the bulbs at once. After all, goods are cheap, labor is expensive, and Christmas is short.

I suggest that policymakers think about the “economic medicine” for the COVID-19 crisis in the same way. Governments should choose quick options that keep the economy’s lights on without worrying too much about costs. After all, people are the important thing, money is cheap, and this medical shock is transient.

This economic crisis is different

Economic crises are like buses; there’s always another one coming along. But this one is different, and it is different in two main ways.

The underlying shock has hit all the G7 nations and China at the same time. Unlike other recent crises, the COVID-19 economic crisis did not start (economically) in one or two nations and then spread to many others. The medical shock, as measured by the number of new cases, started in China in late 2019, but it was only a matter of a few days before cases showed up in some G7 nations. By the end of January 2020, every G7 nation had at least one case.

The medical shock is striking the economy at multiple sites. The most-studied economic crises start at one site. Banking crises start with the banks, exchange rate crises start in the forex market and central bank reserves, sudden-stop crises start with international capital flows, and so on. This one is not like that.

Three types of economic shocks

To organize thinking about what we should do, we need to “simplify to clarify” when it comes to the nature of the economic shocks that the virus has sparked. Three facets are key, as my Graduate Institute of Geneva colleague Beatrice Weder di Mauro and I outline in our recent e-book, Economics in the Time of COVID-19.

First, the disease hits output by putting workers into their sickbeds. This is like temporary unemployment, or economically, it is like August in Europe: the labor force “downs tools,” but only temporarily. In the US and some other nations, this may also lead to a direct hit to spending, since some workers do not get paid when they are sick. Others are in the “gig economy,” where they don’t get paid if they don’t work.

Second are the public-health-related containment measures aimed at flattening the epidemiological curve: factory and office closures, travel bans, quarantines, and the like.

Third is the expectations shock. As did the 2008–09 global financial crisis, the COVID-19 crisis has consumers and firms all around the world crouched in a wait-and-see mode. This is most obvious in the massive drop in travel and hotel stays—but probably only because those data are released so fast. Leading indicators such as the purchasing manager indices (PMIs) are all down sharply.

Strike sites: Where are the three types of shocks striking the economy?

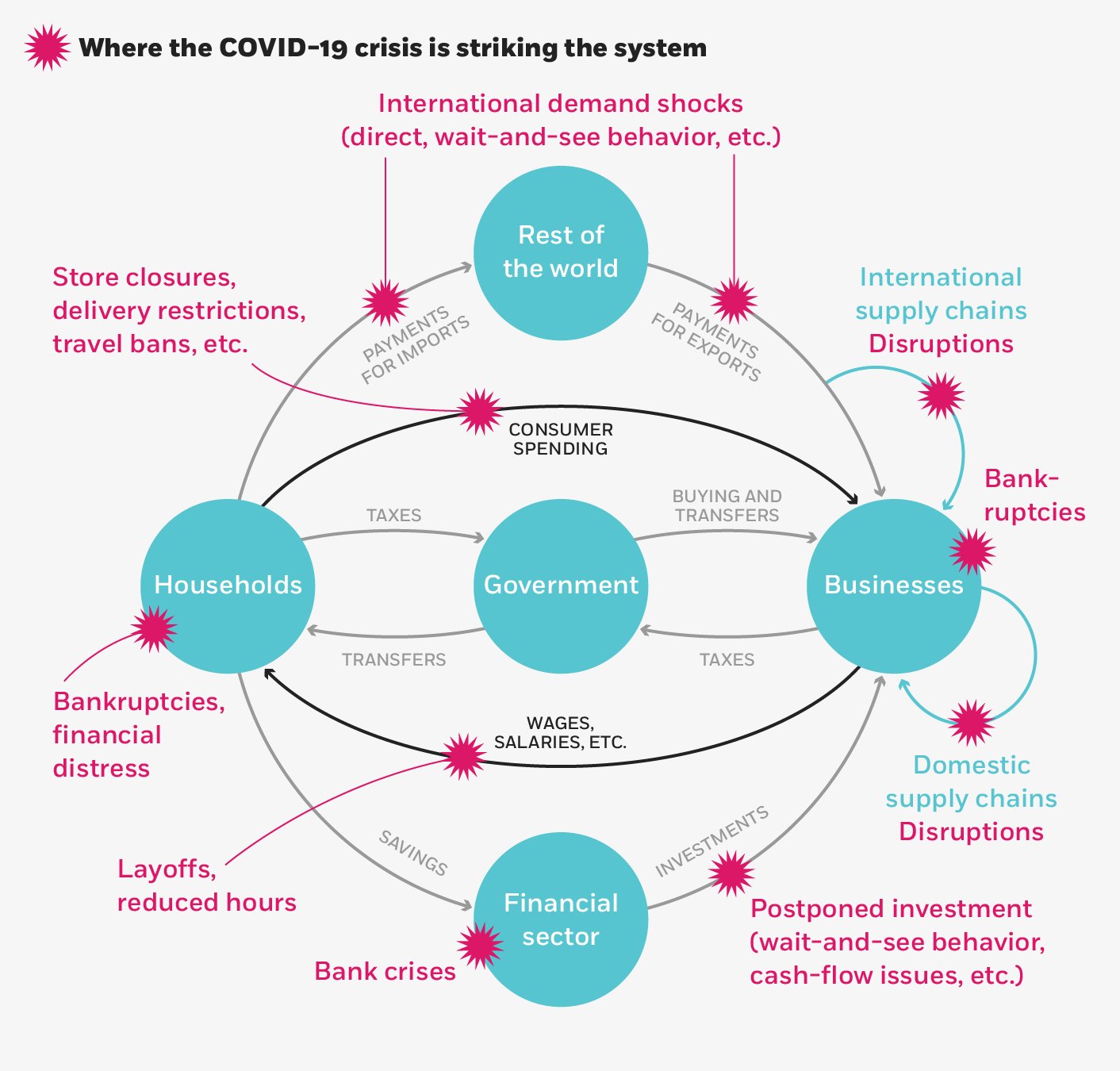

The COVID-19 crisis has struck the economic “machine” in several places at the same time, as seen in the diagram below.

Disruptions throughout the circular flow of income

Households, businesses, governments, the financial sector, and foreign entities all keep money moving around the economy to each other. The COVID-19 crisis threatens this flow at numerous points.

Baldwin 2020

The figure displays a version of a well-known circular money flow diagram used in economics textbooks. In simplified form, households own capital and labor, which they sell to businesses, who use it to make things that households then buy with the money businesses gave them, thereby completing the circuit and keeping the economy ticking over.

The key point is that the economy continues running only when the money keeps flowing around the circuit. Roughly speaking, a flow disruption anywhere causes a slowdown everywhere. The diagram here adds in a few more complications by allowing for a government and foreigners. It also separates consumption expenditure and investment expenditure.

The red starbursts show where the three types of shocks can disrupt, or are disrupting, the flow of money—the economic dynamo, as it were. Starting from the far left and moving clockwise:

Households that don’t get paid may experience financial distress or even bankruptcy—especially in the US, where medical bills are a major source of people going broke, according to bankruptcy statistics published by Debt.org. This reduces spending on goods, and thus the flow of money from households to the government and firms.

The domestic demand shocks hit the nation’s imports and thus the flow of money to foreigners. This doesn’t directly hit domestic demand, but it dampens foreign incomes and thus spending on the nation’s exports. This can slash the flow of money into the nation that used to be coming from export sales. In the 2008–09 global financial crisis, these two strike zones were particularly important, leading to what came to be known as the Great Trade Collapse.

The drop in demand and/or direct supply shocks can lead to a disruption in international and domestic supply chains. Both lead to further reduction in output—especially in the manufacturing sectors. The hit to manufacturing can be exaggerated by the wait-and-see behavior of people and firms. Manufacturing is especially vulnerable since many manufactured goods are postpone-able—things you can wait for without huge costs for at least a few weeks or months.

Businesses are forced into bankruptcy. Many businesses have loaded up on debt in recent years, according to the Bank for International Settlements’ 2019 Annual Economic Report, so they may be vulnerable to reductions in the cashflow. The bankruptcy of the British airline Flybe is a classic example. This sort of shutting down of firms creates further disruptions in the flow of money. Creditors don’t get paid, and workers often don’t get paid fully, and in any case become unemployed. To the extent that the firms that go under are suppliers to or buyers from other firms, the bankruptcy of one can put other firms in danger. This sort of chain-reaction bankruptcy has been seen, for example, in the construction industry during housing crises.

Labor is disrupted by layoffs, sick leaves, quarantines, or leaves to care for children or sick relatives. This is the last but perhaps most obvious of the strike zones. When workers lose their jobs—even when they have unemployment insurance or other income support—they tend to cut back spending on less necessary, more postpone-able items. The precautionary motives may be less evident for workers who keep their jobs but are taking leave, but as mentioned, this sort of leave is not recompensed in all G7 nations, or not for very long.

What should governments do?

The basic principle should be: keep the lights on. The COVID-19 crisis was sparked by a medical shock that will dissipate. It does not seem to be an especially deadly pandemic, so although many will die and each death is a tragedy, it is not like the plague; the workforce will not be reduced significantly on a permanent basis. The key is to reduce the accumulation of “economic scar tissue”—reduce the number of unnecessary personal and corporate bankruptcies, and make sure people have money to keep spending even if they are not working. A side benefit of this would be to subsidize the sort of self-quarantine that is needed to flatten the epidemiologic curve.

A number of excellent plans have already been proposed. My favorite, by Paris School of Economics’ Agnès Bénassy-Quéré and her coauthors, was posted on VoxEU.org on March 11.

Richard Baldwin is professor of international economics at the Graduate Institute, Geneva; founder and editor-in-chief of VoxEU.org; and former president of the Center for Economic and Policy Research.

This article originally appeared on VoxEU.org. VoxEU’s coverage of the COVID-19 crisis, which can be accessed here, includes two free e-books: “Economics in the Time of COVID-19” and “Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes,” which explains the fiscal response the crisis demands.

- Richard Baldwin, The great trade collapse: causes, consequences and prospects, Washington, D.C.: CEPR Press, 2009.

- Richard Baldwin and Beatrice Weder di Mauro, Economics in the Time of COVID-19, Washington, D.C.: CEPR Press, 2020.

- Rudolfs Bems, Robert C. Johnson, and Kei-Mu Yi, “The Great Trade Collapse,” Annual Review of Economics, 2013.

- Bank for International Settlements, “Annual Economic Report,” June 2019.

- Al Krulick, “Bankruptcy statistics,” Debt.org, accessed March 20, 2020.

- N. Gregory Mankiw, Macroeconomics (7th edition), New York: Worth Publishers, 2010.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.