The Volkswagen Emissions Scandal Is Déjà Vu All Over Again

- By

- December 01, 2015

- CBR - Marketing

In the James Bond classic Dr. No, Sean Connery’s brilliant Bond deadpans to the title character, “World domination. The same old dream.” The world’s big car manufacturers may not have dreamed of world domination exactly, but many of them have aspired to hold the industry’s top position. And like the fictitious Dr. No, they have ended up in hot water.

One has to go back a few decades, to the 1980s and 1990s, to fully understand the decline of the longtime market-share leader, General Motors. The chart excerpted from a paper written by University of Washington’s Fred Mannering and Brookings Institution’s Clifford Winston, shows how GM lost share over time—falling from a high of almost 50 percent in 1979 to mid-30 percent by 1989.

In large part this decline can be attributed to the organization’s hubris. As the Economist noted in 1998,

All empires contain the seeds of their own destruction. The ideas on which they were founded cannot adapt to changing times. Their wealth creates bureaucracy and complacency. . . . Today, GM pops up in management books only as an example of what not to do—blamed for not introducing products quickly enough, for poor labour relations and so on.

The Japanese manufacturers—led by Toyota, Honda, and Nissan—marched forward armed with concepts such as total quality management and continuous improvement, to gradually raise their share of the US market. By focusing on their own perceived invulnerability, rather than on their customers, employees, and other stakeholders, GM squandered the brand loyalty and reputation that it had taken for granted. The result: it lost market share and, eventually, profits.

Fast-forward to 2002. With GM in trouble, executives at Toyota set an ambitious goal: to increase the company’s share of the global auto industry to 15 percent by 2010. With that share, it would overtake GM to become the world’s largest car manufacturer. But to accomplish this, Toyota would have to grow by a whopping 50 percent in eight years, which would not be easy. The company would need to build capacity in many countries, and to introduce a veritable slew of car models to cater to consumer groups they had not been targeting.

Well, Toyota managed to reach its goal. Remember, though, that the reason to have a large market share is to be able to leverage the good experiences consumers have with a product and convert those people into loyal customers. Consumers had been purchasing Toyota cars year after year for quality and reliability. Unfortunately, in the quest to grow, Toyota sacrificed the one thing it could not afford to sacrifice.

By 2010, Toyota had achieved its goal—but also recalled tens of millions of cars due to faulty gas pedals. As the New York Times noted, “Toyota managed to win bragging rights as the world’s biggest car company. But that focus on rapid growth appears to have come at a cost to its reputation for quality, creating an opportunity for others to potentially take back market share they lost to Toyota.” Three of Toyota’s top cars fell off the Consumer Reports list of recommended vehicles.

Just five years later, we see a car company suffering a similar fate. In the first half of 2015, Volkswagen sold 5.04 million units, compared to 5.02 million sold by Toyota and 4.86 million sold by GM. This was in line with the strategy of former Volkswagen Group CEO Martin Winterkorn, who in 2011 reportedly said, “By 2018, we want to take our group to the very top of the global car industry.” With a goal of making Volkswagen “the world’s most profitable, fascinating and sustainable automobile manufacturer,” the company set a sales target of more than 10 million vehicles. They also made it a goal to have the most satisfied employees and customers. A key part of this strategy was the US market, where the demands on fuel efficiency are higher and the company saw “clean diesel” as a pathway to a larger customer base.

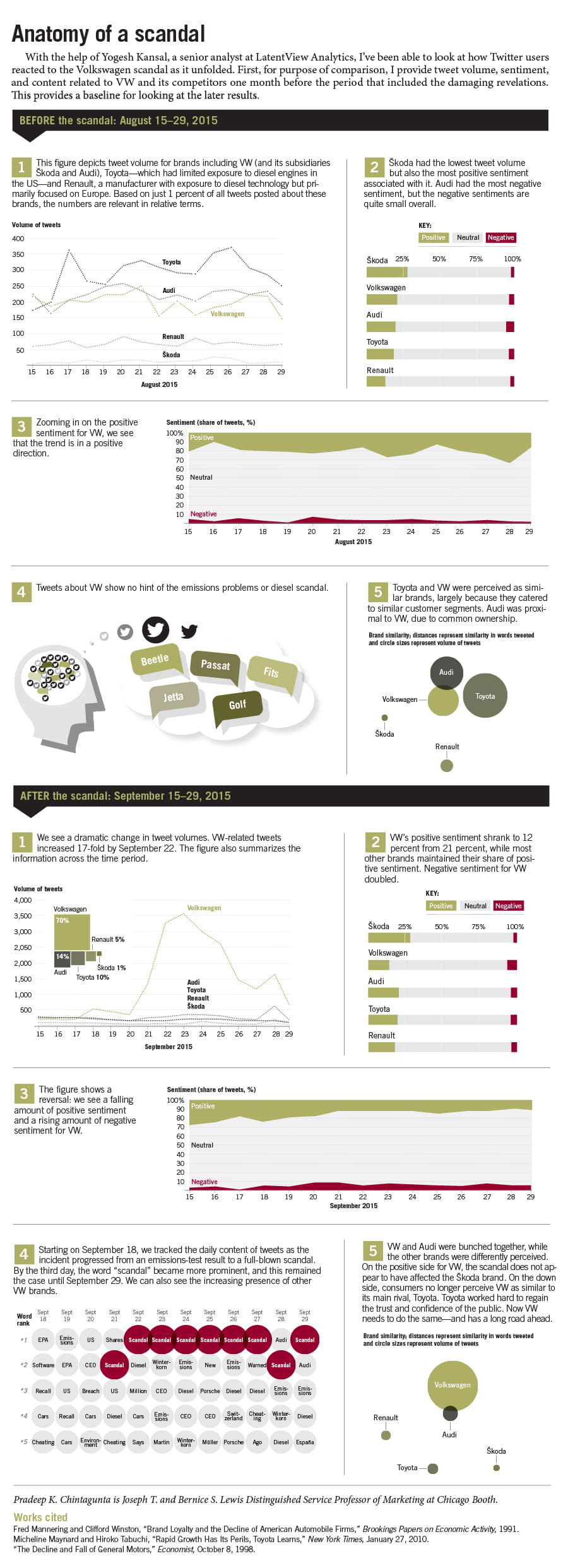

That brings us to the present day. In September, the US Environmental Protection Agency announced that Volkswagen had installed software designed to help clean-diesel cars cheat on emissions tests. The company quickly admitted that 11 million cars sold worldwide were similarly affected. Winterkorn resigned. The company halted US sales of clean-diesel vehicles and its stock tanked.

There’s a basic message that these auto-industry CEOs seem to forget: being the biggest does not make you the best. If anything, it’s the other way around—if you are the best, you may become the biggest; and if you want to remain the biggest, you’ll have to stay the best. Now car-company CEOs may be left hoping for a sentiment aptly expressed in the movie Inside Out, in which four emotions in the mind of a girl named Riley are represented as characters. The character Sadness warns her friend Joy about walking through Riley’s mind: “It’s long-term memory. You’ll get lost in there.” Indeed, Toyota and now Volkswagen may hope that their product recalls, and the incidents that prompted those recalls, get lost in the long-term memories of consumers.

- Fred Mannering and Clifford Winston, "Brand Loyalty and the Decline of American Automobile Firms," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1991.

- Micheline Maynard and Hiroko Tabuchi, "Rapid Growth Has Its Perils, Toyota Learns," New York Times, January 27, 2010.

- "The Decline and Fall of General Motors," Economist, October 8, 1998.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.