In the environmental arena, firms that receive poor ratings tend to reduce their toxic emissions more than companies rated favorably or not at all.

- By

- March 06, 2015

- CBR - Public Policy

In the environmental arena, firms that receive poor ratings tend to reduce their toxic emissions more than companies rated favorably or not at all.

Companies often get rated on a broad range of nonfinancial measures, from corporate social-responsibility initiatives to investor-relations websites. As much as a company may want to ignore these outside ratings, especially if it receives poor grades, it can’t do so easily: investors, consumers, and employees pay attention to the ratings, too.

In the environmental arena, firms that receive poor ratings tend to reduce their toxic emissions more than companies rated favorably or not at all, according to previous research by Duke’s Aaron K. Chatterji and Harvard’s Michael W. Toffel. Now research suggests that ratings have spillover effects, with rated firms reducing their emissions even more when their peers are also rated. And rated peers can even impact companies that haven’t been rated.

Chicago Booth’s Amanda Sharkey and University of Utah’s Patricia Bromley used the environmental ratings of manufacturing firms, as well as data that firms are required to report to the government about their pollution levels, to track how the pollution levels of both rated and unrated firms changed as a function of having more rated peers.

To do this, they used environmental-index reports created by KLD Research and Analytics (now MSCI), which rates hundreds of US-based firms focused on waste-management treatment, electrical utilities, chemical manufacturing, and mining. These ratings are the oldest and most prominent social ratings in the industry, and they matter because the “[rated] firms have a large impact on the environment,” says Sharkey.

The researchers tracked the companies’ annual number of pounds of toxic emissions, looking at each company added to the ratings list between 2001 and 2004, and at firms that remained unrated during that period.

Sharkey and Bromley find that being rated, regardless of the rating received, did prompt a company to reduce its toxic emissions, consistent with prior research. Moreover, on average, the more peers that were rated in an industry, the greater a rated firm’s drop in emissions.

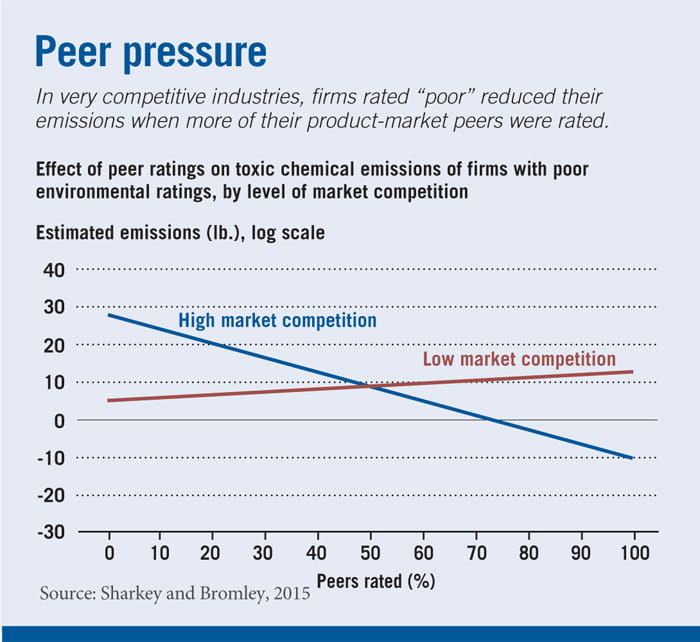

However, the researchers find that the type of rating a firm received and the context in which it operated played an important role in whether a firm cut emissions in response to rated peers. Firms rated “good” or “neutral” reduced their pollution when more peers were rated, regardless of how much regulation or competition they were subject to. In contrast, firms that were rated “poor” only reduced their emissions in response to rated peers when they were in either highly regulated or very competitive industries.

Moreover, in highly regulated industries, ratings prompted even unrated businesses to lessen their environmental footprint. “It was a shock to these firms, when suddenly more of their peers were being rated,” says Sharkey, hypothesizing that companies were reluctant to get left behind.

Sharkey says that while third-party ratings can promote change and prompt self-policing, these types of evaluations seem to work most effectively when they operate in tandem with regulation and market forces, such as competition. “Emerging types of private regulation, such as ratings, should not be seen as a surefire substitute for more traditional ways of bringing about change,” write the researchers. “Rather, it may be more sensible to view ratings and regulation as complements.”

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.