Note to Yellen: Knock Off the Time-Based Guidance

Why the Fed should mind its language.

- By

- August 24, 2016

- CBR - Economics

The most powerful voice in financial markets arguably belongs to the US Federal Reserve, which can send all manner of tradable assets zinging with seemingly mundane comments.

Lately the Fed’s words have been moving markets in unintended ways, according to a study by a group of economists working on and off Wall Street. Since 2011, forward guidance—regular Fed statements intended to manage market expectations about potential interest-rate changes—has led investors to discount macroeconomic events that would normally affect the price of assets, according to the research. Their inattention, in turn, eventually undermines the Fed’s mission of optimal monetary policy.

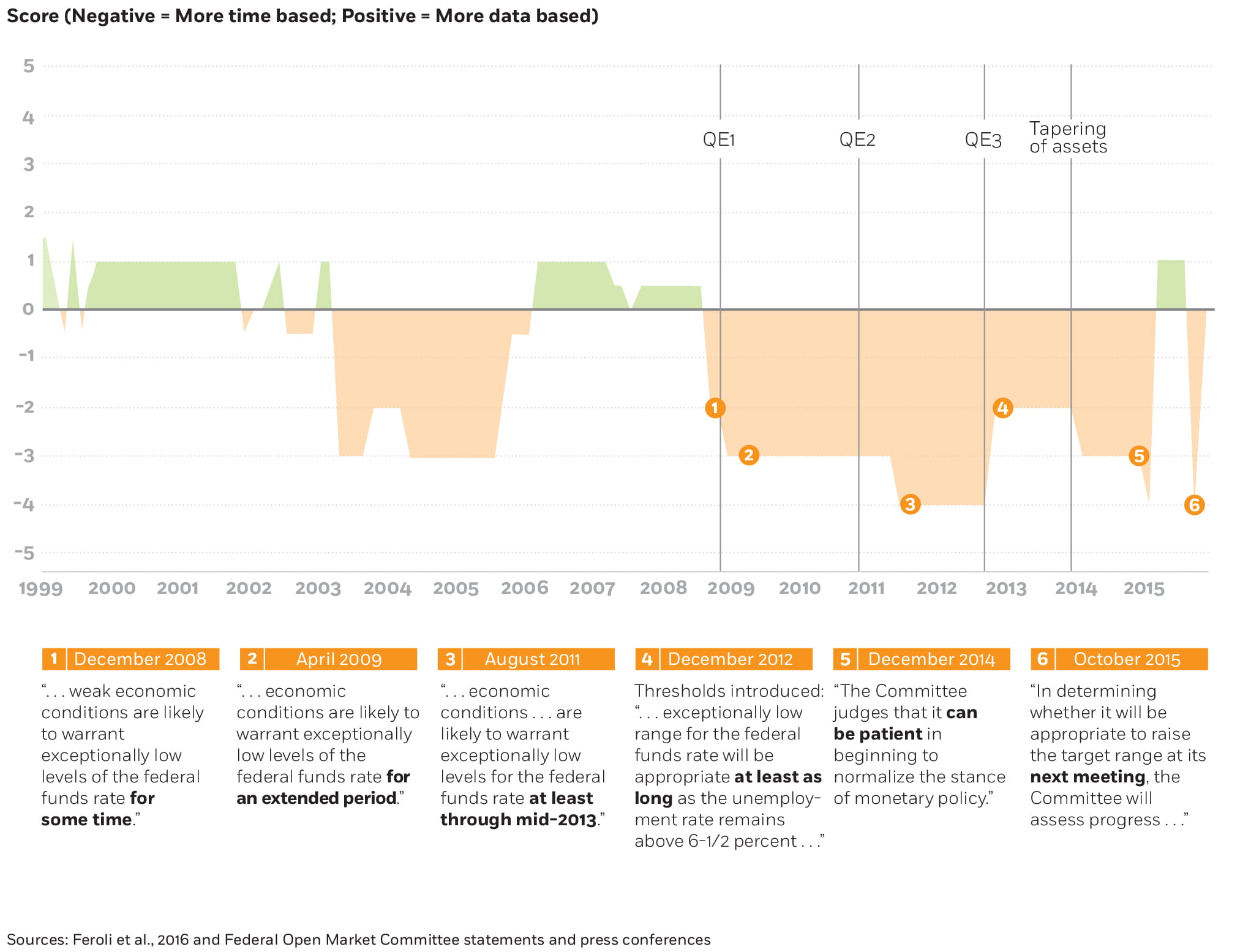

Analyzing 20 years of Fed communications, the researchers trace the problem to a subtle shift in the content of forward guidance. During most of those years, the study finds, forward guidance essentially told investors which microeconomic data would trigger the Fed to raise interest rates. But in times of economic darkness, such as the post–financial crisis years from 2011 to 2015, the Fed also offered strong hints about the calendar timing of potential rate hikes.

The study concludes that data-based guidance typically does a better job of efficiently managing market expectations than time-based guidance. “We expect rates will remain low until the labor market improves,” for example, leads markets to respond rationally to the release of new unemployment figures. Time-based guidance, such as: “We expect rates to remain low through mid-2015,” makes actual events less relevant and investors less certain about how the Fed will respond to those events. It can lead to Fed credibility issues if the data don’t pan out as expected and rate changes need to be delayed or sped up, and those credibility issues can hamper economic growth.

The research—by Michael Feroli of J. P. Morgan Chase, David Greenlaw of Morgan Stanley, Peter Hooper of Deutsche Bank Securities, Frederic Mishkin of Columbia University, and Chicago Booth’s Amir Sufi—sheds light on the problems of managing monetary policy at the zero lower bound, where nominal interest rates are already near zero. It’s difficult territory for central banks, because they cannot use their most popular and powerful tool for sparking economic growth: cutting short-term interest rates. The situation forces central bankers to rely on less direct stimulants, such as words that convince markets to act in certain ways.

“Any mention of a timeline in guidance tends to overshadow the broader message.”

The study describes how Fed speak, with the addition of time-based forward guidance, became a core monetary-policy tool in the days after the 2007–10 financial crisis. With unemployment stalled at 9 percent, and short-term interest rates too low to cut further, the Fed started adding phrases such as “we expect rates to remain low at least through 2013” to reassure investors when ordinary guidance did not.

The researchers conclude that time-based guidance is appropriate at such times, when the Fed is out of options. But they argue that these conditions do not describe the current situation in the United States, and that the Fed should drop time references and return to more-data-driven guidance.

The authors concede that almost all of the Fed’s time-based guidance already comes with data-based qualifications. But in the mainstream financial press, any mention of a timeline in guidance tends to overshadow the broader message. The study offers, by example, a quote from a July 10, 2015, speech by Fed Chair Janet Yellen:

Based on my outlook, I expect that it will be appropriate at some point later this year to take the first step to raise the federal funds rate and thus begin normalizing monetary policy. But I want to emphasize that the course of the economy and inflation remain highly uncertain, and unanticipated developments could delay or accelerate this first step.

The Financial Times, the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal reacted, respectively, with the following headlines: “Yellen Reiterates Case for 2015 Rate Rise,” “Yellen Expects Fed to Raise Rates This Year,” and “Janet Yellen: Fed on Track for 2015 Rate Hike.”

Grading the Fed

During the recession, the Fed started indicating its intention to raise rates by a certain date. But research suggests that data-based guidance does a better job of efficiently managing market expectations. Here researchers score the Fed’s language.

Michael Feroli, David Greenlaw, Peter Hooper, Frederic Mishkin, and Amir Sufi, “Language after Liftoff: Fed Communication away from the Zero Lower Bound,” Working paper, February 2016.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.