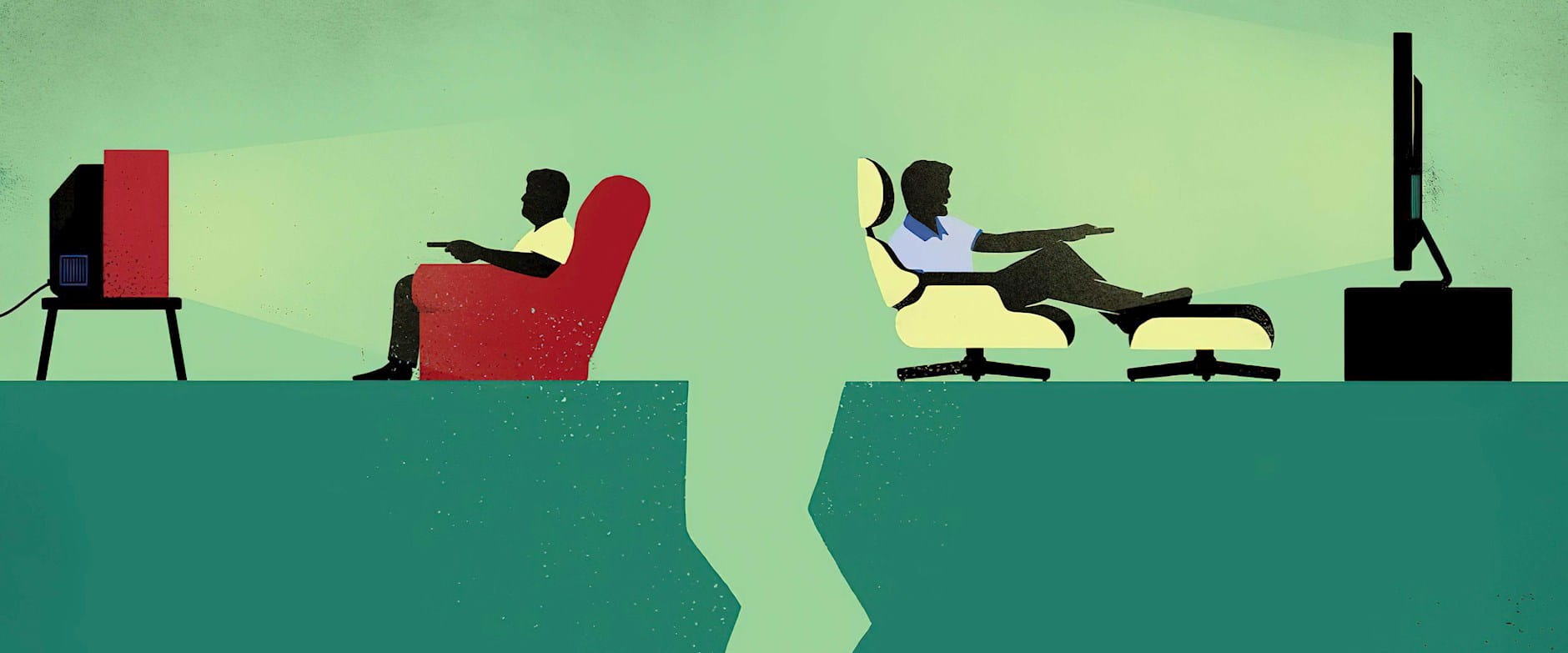

It may seem sometimes like the United States is coming apart. “While rural America watches Duck Dynasty and goes fishing and hunting, urban America watches Modern Family and does yoga in the park,” write Chicago Booth’s Marianne Bertrand and Emir Kamenica. “The economically better-off travel the world and seek out ethnic restaurants in their neighborhoods, while the less well-off don’t own a passport and eat at McDonald’s.” Conservatives, they write, favor masculine names for boys while liberals prefer more-feminine names, and men play video games while women browse Pinterest.

These kinds of cultural splits can have economic, social, and political consequences in that they may ultimately reduce social cohesion within a country. But according to Bertrand and Kamenica, who measured cultural divisions over time, the cultural gap in the US is largely stable—not widening.

The researchers measured cultural divisions over time using multiple data sets, studying the media people consume along with their attitudes and their activities. The researchers then used machine learning and statistical modeling to calculate how reliable specific brands and media were in identifying salient characteristics of various social groups in different years.

The data reveal that divisions definitely exist. Watching certain movies or television shows, reading certain magazines, or buying particular consumer products are predictable markers of traits such as how much money people make or how far they got in school.

For example, if you watched the Super Bowl, real estate shows Property Brothers or Love It or List It, or the Academy Awards in 2016, there was at least a 55 percent probability you had a high income. The same was true if you saw Jerry Maguire orThe English Patient at the movies in 1998, and (by a slightly smaller percentage) if you saw Gone Girl in 2016.

Similarly, not having watched Cops on TV in 2004 or Big Momma’s House at the movies the same year, or having missed Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Out of the Shadows in theaters in 2016 were also good indicators of high income.

Almost all of these shows and movies also reliably predicted a higher level of education, the researchers find. And reading Time, Newsweek, or Consumer Reports proved a good predictor of higher education too.

The predictive power of behaviors and attitudes

Social attitudes, leisure activities, and choices about what products and media to consume can predict various personal characteristics.

Likelihood of correctly guessing each attribute based on knowledge of people's:

Bertrand and Kamenica, 2018

In terms of consumer products, did you use Grey Poupon Dijon Mustard in 1992? That was a good predictor of high income for that year 62 percent of the time. In 2016, the best determinant of high income was owning an iPhone (69 percent predictive) or iPad (67 percent predictive). iPhone ownership was particularly instructive: “Across all years in our data, no individual brand is as predictive of being high income as owning an Apple iPhone in 2016,” the researchers write.

But while the divisions these media and products illustrate are real and deep, they are not new—indeed, they have been “nearly constant across the last quarter century,” write Bertrand and Kamenica. “It is nonetheless striking that the cultural gap has been constant even as the number of options has changed substantially.” Movies change, magazines come and go, and TV shows multiply, but the gap in how different groups consume entertainment and spend their money remains the same.

To measure this division, the researchers considered all the television shows or products that were available in the data in the years they studied. (The exact years studied varied depending on the data set.) The titles and products to watch, read, and buy changed from year to year, but this was reflected in the data. For example, the researchers analyzed Mediamark Research Intelligence data, which is based on questionnaires that asked people whether they had seen any of a few dozen movies—and the movies included in the questionnaire changed from year to year.

The researchers also fail to find evidence of an increasing cultural gap between men and women in terms of media consumption and social attitudes. The way men and women used their time became more similar between 1965 and the mid-1990s, but convergence has stopped since. Differences in men’s vs. women’s buying, media habits, and attitudes stayed relatively stable over the years. Many men like action, thriller, and sci-fi movies, while women opt for dramas and romantic comedies. Men may buy Sports Illustrated, while women pick up fashion and housekeeping magazines.

The researchers do find a widening gap between the behavior of white and nonwhite consumers. But by far the most striking exception to the overall pattern of stable cultural distances is with regard to the social attitudes of Democrats and Republicans. “We find that liberals and conservatives are more different today in their social attitudes than they have ever been in the last 40 years,” write Bertrand and Kamenica. “Divergence has been greatest in views on marriage, sex and abortion, voting participation and religion, and confidence.” This is in line with a study by Christopher Hare and Keith T. Poole of the University of Georgia at Athens that finds the Democratic and Republican Parties are more polarized than at any time since the Civil War. But again, most of the differences studied sharpened between the 1970s and ’90s.

- Marianne Bertrand and Emir Kamenica, “Coming Apart? Cultural Distances in the United States over Time,” Working paper, July 2018.

- Christopher Hare and Keith T. Poole, “The Polarization of Contemporary American Politics,” Polity, July 2014.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.