Ride sharing and self-driving cars may transform cities, but the key to really understanding modern metropolitan areas is the steam locomotive, according to new research.

Steam locomotives and railways dramatically redefined cities by separating business and manufacturing districts from residential areas, argue University of Bristol’s Stephan Heblich, Princeton’s Stephen J. Redding, and London School of Economics’ Daniel M. Sturm.

The researchers analyzed more than a century of London’s demographics along with its commercial and residential development. They used London as a prototype of sprawling modern metropolises, in which vast numbers of people live significant distances from where they work.

They find that the development of the steam engine and rail network—more than the cotton gin, light bulb, telegraph, automobile, or airplane—may have been the single biggest factor in modern London’s growth.

When the steam locomotive was invented in the early 19th century, it more than tripled average travel speeds, from 6 mph to 21 mph. Greater London’s growth took off with the building of the city’s suburban rail network and the London Underground. Many cities around the world have since experienced the same phenomenon, and today, China’s rapidly growing urban areas are rushing to build networks of subways and light-rail systems for commuters. By 2020, China’s rapid-transit system could span 4,000 miles and cost $300 billion all told.

In 1801, the researchers report, London had a population of 1 million and spanned 5 miles east to west. A century later, London was the world’s largest city, with 6.5 million people. It measured 17 miles across—a sprawl, the researchers conclude, that is another legacy of the British capital’s extensive railway network.

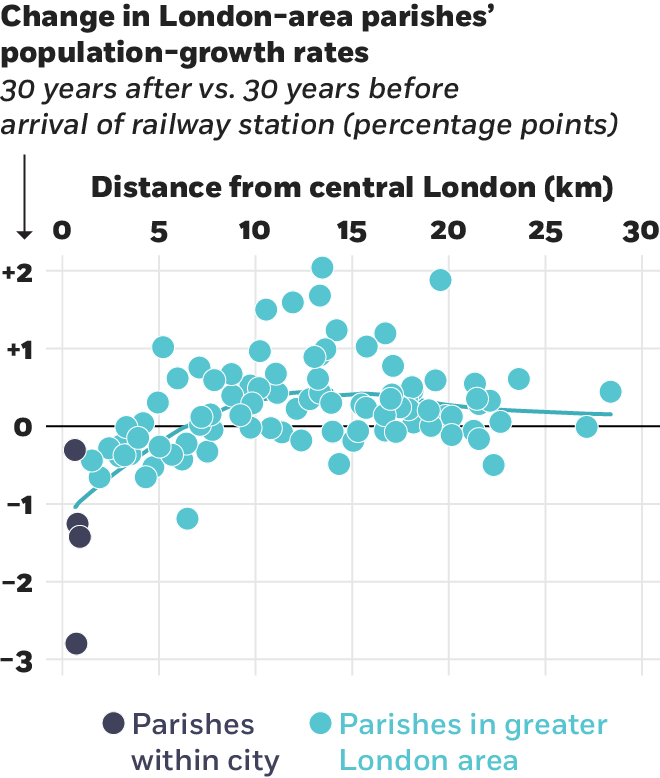

Following the arrival of the railway, they find, there was a reduction in relative population growth in civil parishes close to the center of Greater London, and an increase in relative population growth in parishes further out.

Heblich et al., 2018

“We find that much of the aggregate growth of Greater London can be explained by the new transport technology of the railway,” the researchers write. “Steam railways dramatically reduced travel times and hence permitted the first large-scale separation of workplace and residence to realize economies of scale” in business and manufacturing districts as well as services and amenities in residential areas.

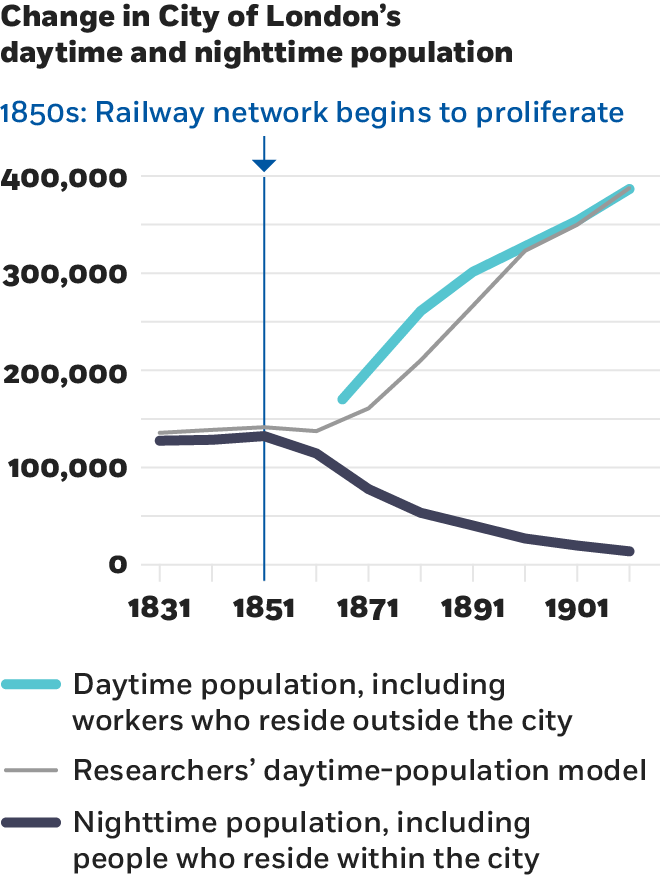

The researchers explain these findings using a model of what they call the “spatial organization of economic activity within Greater London,” or peoples’ decisions about where to live and work within the city. Using data on bilateral commuting in 1921 and information on employment by residence and land values dating back to the early 19th century, they predict the impact of the construction of the railway network on employment by workplace in Greater London as early as 1831, before the construction of the first railway, in 1836.

The model successfully captures the sharp divergence between the night-time and day-time population in the City of London from the mid-19th century onward, and is also able to replicate the early commuting data, which show that at the dawn of the railway age, most people lived close to where they worked.

Removing the entire rail network, according to the model, would reduce Greater London’s population by 30 percent and “decrease commuting into the City of London from more than 370,000 in 1921 to less than 60,000,” the researchers write. By comparison, removing only the London Underground (or the “Tube”) would diminish the population by 8 percent and lower commuting into the city to just under 300,000.

Stephan Heblich, Stephen J. Redding, and Daniel M. Sturm, “The Making of the Modern Metropolis: Evidence from London,” Working paper, September 2018.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.