How a Crowdsourcing App Can Stop People from Overspending

- By

- August 22, 2019

- CBR - Economics

A rational economic actor would not spend more than she takes in. Yet, other factors—from limited income, to financial illiteracy, to the urge to keep up with friends or peers—all create frictions between the advice to spend and save wisely and the opposing reality.

The Status app

Research by Boston College’s Francesco D’Acunto, Georgetown’s Alberto G. Rossi, and Chicago Booth’s Michael Weber suggests a way to bridge that gap, by using a combination of crowdsourced information and peer pressure.

The researchers made use of a free fintech application, Status, which requires users to plug in their age, location, income, credit score, and homeownership status. The app crunches these data and sorts users into peer groups of at least 5,000 other users who share similar financial profiles. Status then shows users how their average monthly spending stacks up against their peers’, with the intention of motivating people to improve their spending habits.

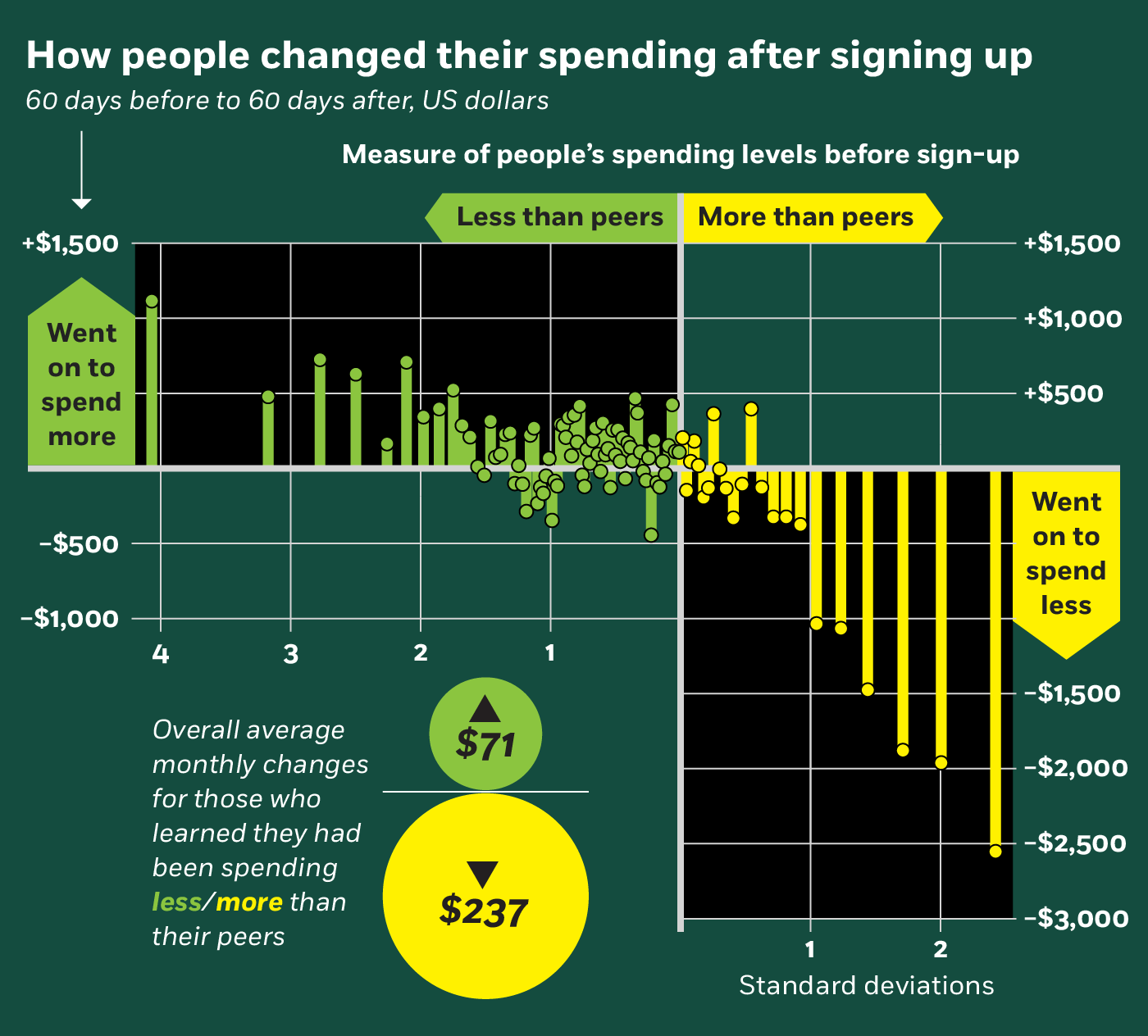

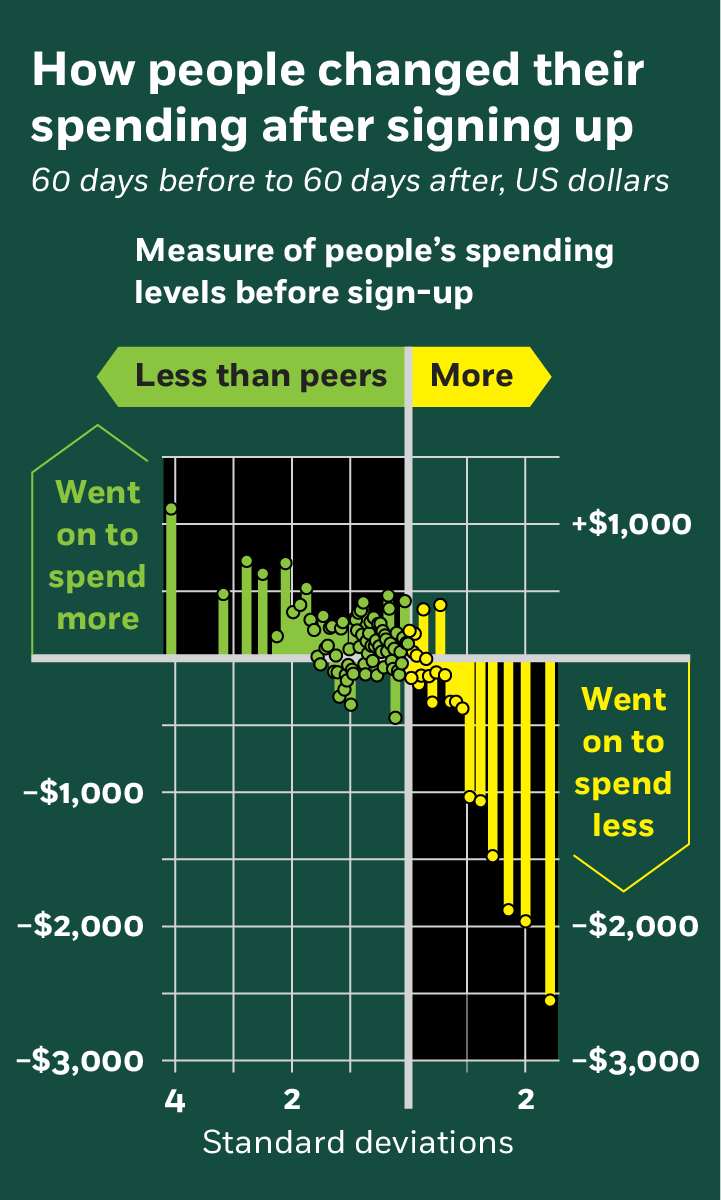

“On average, users that overspend relative to peers reduce their seasonally-adjusted spending by $237 per month. . . . Users that underspend increase their seasonally-adjusted consumption spending by $71,” write the researchers, who analyzed data from almost 18,000 Status users between September 2017 and October 2018.

D’Acunto et al., 2019

Exposure to the app’s crowdsourced information was so powerful that “all the users that overconsume relative to peers reduce their monthly spending, whereas all the users that underconsume relative to peers keep constant or increase slightly their monthly consumption spending.”

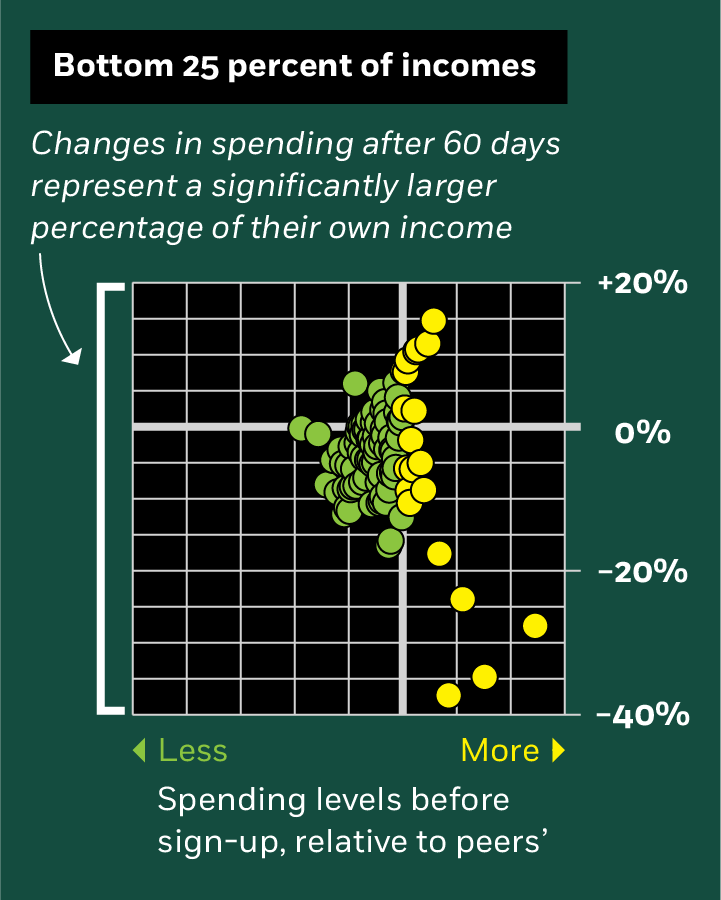

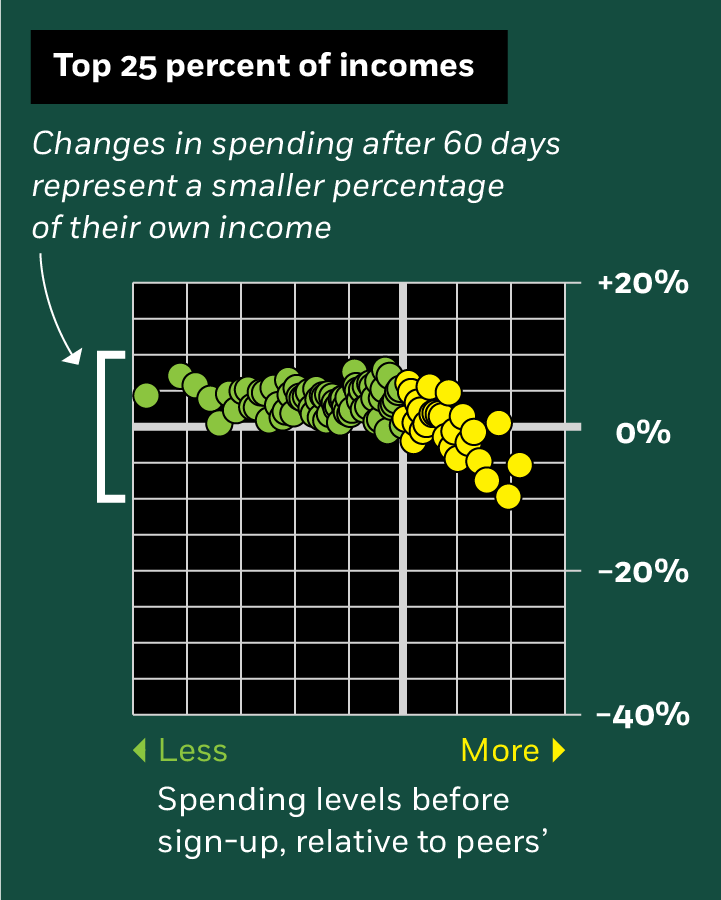

The researchers also observe that the further away users were from their peers’ spending, the more they adjusted their own consumption. However, the response was asymmetrical: users that were significantly overspending with respect to their peers cut their monthly spending (adjusted for income) by 12 percent during the first two months of signing up for Status. The effect was much larger for lower-income users, who cut their monthly spending by about 30 percent. Meanwhile, people who significantly underspent relative to their peers increased their consumption by about only 1 percent.

Spending adjustments are a bigger deal for people with lower incomes

60 days before to 60 days after (as a share of people’s own income)

D’Acunto et al., 2019

Overspenders’ entire adjustment came from discretionary spending (as nondiscretionary spending, almost by definition, can’t be changed), and overspending households sharply cut cash withdrawals. In general, receiving bad news about their relative spending habits—that they were spending more than their peers—was more motivating for Status users than finding out they were spending less than their peers, the researchers find.

Fintech apps, they write, “can provide a cost-effective and vivid, salient way to transmit financial literacy.”

Francesco D’Acunto, Alberto G. Rossi, and Michael Weber, “Crowdsourcing Financial Information to Change Spending Behavior,” Working paper, February 2019.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.