To the frustration of financial counselors everywhere, millions of people doom themselves to perpetual debt by repeatedly taking out small but expensive short-term loans they can barely afford. In the United States, these typically come from payday or car title lenders and go to financially strapped individuals. In developing countries, small-scale entrepreneurs rely on daily or weekly loans for working capital. In both cases, borrowers pay exorbitant interest rates and, often, additional fees to extend a loan over and over. Interest payments can quickly add up to more than the loan amount.

Understanding how people get sucked into these debt traps is an important public-policy issue, according to Northwestern’s Dean Karlan, Chicago Booth’s Sendhil Mullainathan, and Harvard’s Benjamin N. Roth. They conducted a series of experiments with indebted entrepreneurs in India and the Philippines and find that having their short-term loans paid off took the participants out of debt only temporarily. The entrepreneurs in question quickly took out new, profit-sapping loans.

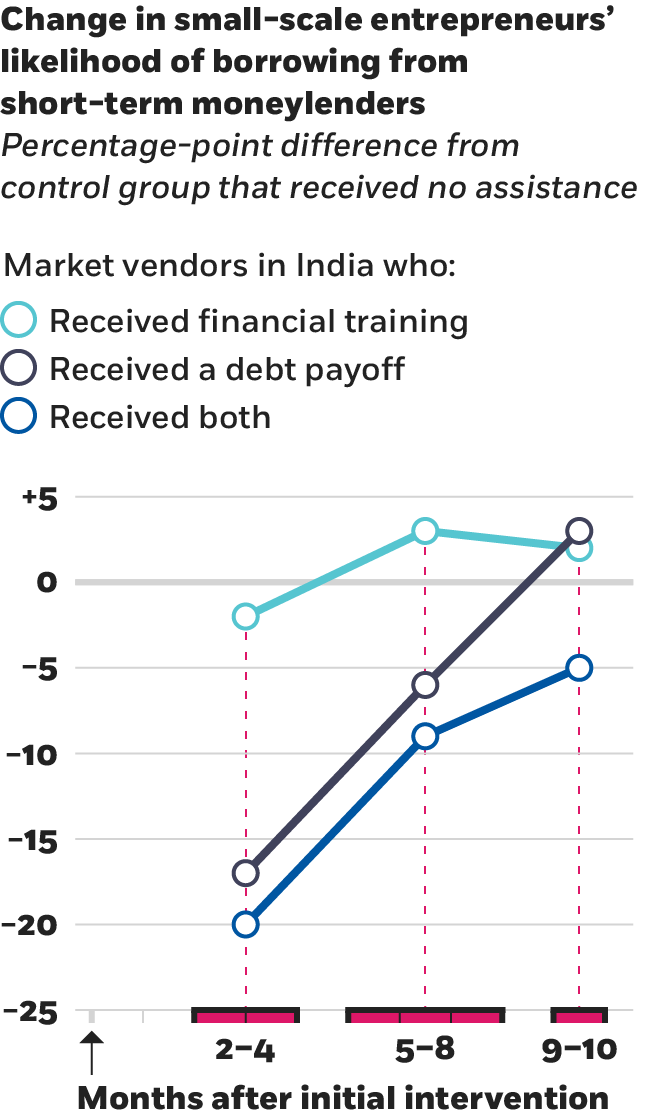

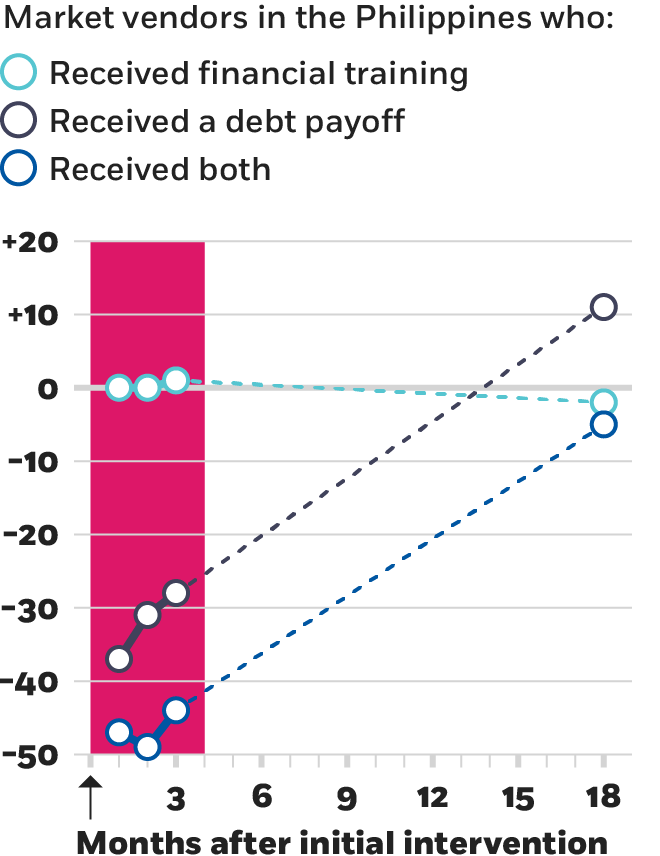

In these experiments, completed in 2007 and 2010, the researchers provided brief financial training to market vendors who had high-interest debt. The Indian entrepreneurs were paying average monthly rates of 432 percent, while the Philippine borrowers averaged 13 percent in monthly interest costs, according to the study. By comparison, annual rates on payday loans in the US range from about 390 to 780 percent (according to the nonprofit Consumer Federation of America). The training delivered the message that borrowing from moneylenders was far more expensive than alternatives such as reducing consumption.

The researchers then paid off the moneylender debts of some of the participants—in India, the reduced interest was equivalent to doubling their income. The remaining participants served as a control group. Participants completed four follow-up surveys between a month and two years after the repayments.

Karlan et al., 2018

Within two years, debt levels for the vendors whose debts had been paid off rose back to the level of the control group, the researchers find. Most vendors fell back into debt within six weeks, even though some of them generated considerably higher profits after the repayment because their profits weren’t being eaten up by interest payments.

Financial training may have only delayed the entrepreneurs from returning to lenders, according to the researchers. Across the board, debt relief did not affect spending habits. The entrepreneurs with paid-off loans were no more likely to have savings after two years than the others, Karlan, Mullainathan, and Roth report.

Poverty and scarcity affect decision making, other research finds. (See “How poverty changes your mind-set,” Spring 2018.) Understanding the reasons behind such continued borrowing is important for policy makers in addressing predatory lending, including high-interest loans offered to small-scale entrepreneurs. Restrictions on such lending would not make sense, for example, if the loans helped vendors to significantly increase their earnings, the researchers write. In addition, if these loans save borrowers from destitution because of unexpected bills or wage losses, improving social services might be more helpful than outlawing lending.

Some high-interest debt appeared to be justified, such as when vendors were able to increase profits by investing the borrowed money in their businesses, the study finds. However, if vendors were going to be wise about the debt, they would have used the new profits to get debt-free again, which they didn’t do.

Some appeared to stay maxed out on expensive loans because they were repeatedly hit with financial shocks. In that case, the research indicates, making a one-time payoff simply enabled more borrowing. Karlan, Mullainathan, and Roth suggest that a better understanding of how vendors spend borrowed funds is needed to craft policies that might prevent these debt cycles.

Dean Karlan, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Benjamin N. Roth, “Debt Traps? Market Vendors and Moneylender Debt in India and the Philippines,” Working paper, April 2018.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.