An acquaintance recently wrote to me about her daughter, Olivia. Olivia is a 29-year-old diabetic woman on the autism spectrum. These days, she regularly walks a 2-mile trek through her small, rural community in the western United States. But only a few years ago, she hardly walked at all. She doesn’t drive, so she would walk to the grocery store or to restaurants near her house if no one was around to drive her, but otherwise she found walking boring and preferred to stay home. Then she downloaded Pokémon GO.

Growing up in the late 1990s, Olivia was a big Pokémon fan. So when Pokémon GO came out in 2016, she was excited to start playing again. The game uses your phone’s GPS and clock to detect where and when you’re in the game and make Pokémon characters “appear” around you so you can go and catch them. Soon after downloading the game, Olivia started taking her 2-mile walks. That route was the best for catching Pokémon. The game gave her a reason to go out and walk—this was the Pokémon journey she’d dreamed of going on since she was 10 years old.

Olivia’s isn’t the only story I’ve heard about Pokémon GO motivating more exercise. In fact, the game was a big reason my eight-year-old son and I started taking walks around our neighborhood, and it was so wildly popular when it first came out that researchers estimate the game added 144 billion steps across the US at its peak, in summer 2016. It was so successful that people blamed Pokémon GO for getting too many distracted walkers out on the streets.

Pokémon GO motivated so much exercise—more than other exercise apps—because it relied on people’s intrinsic motivation. It turned walking into a game.

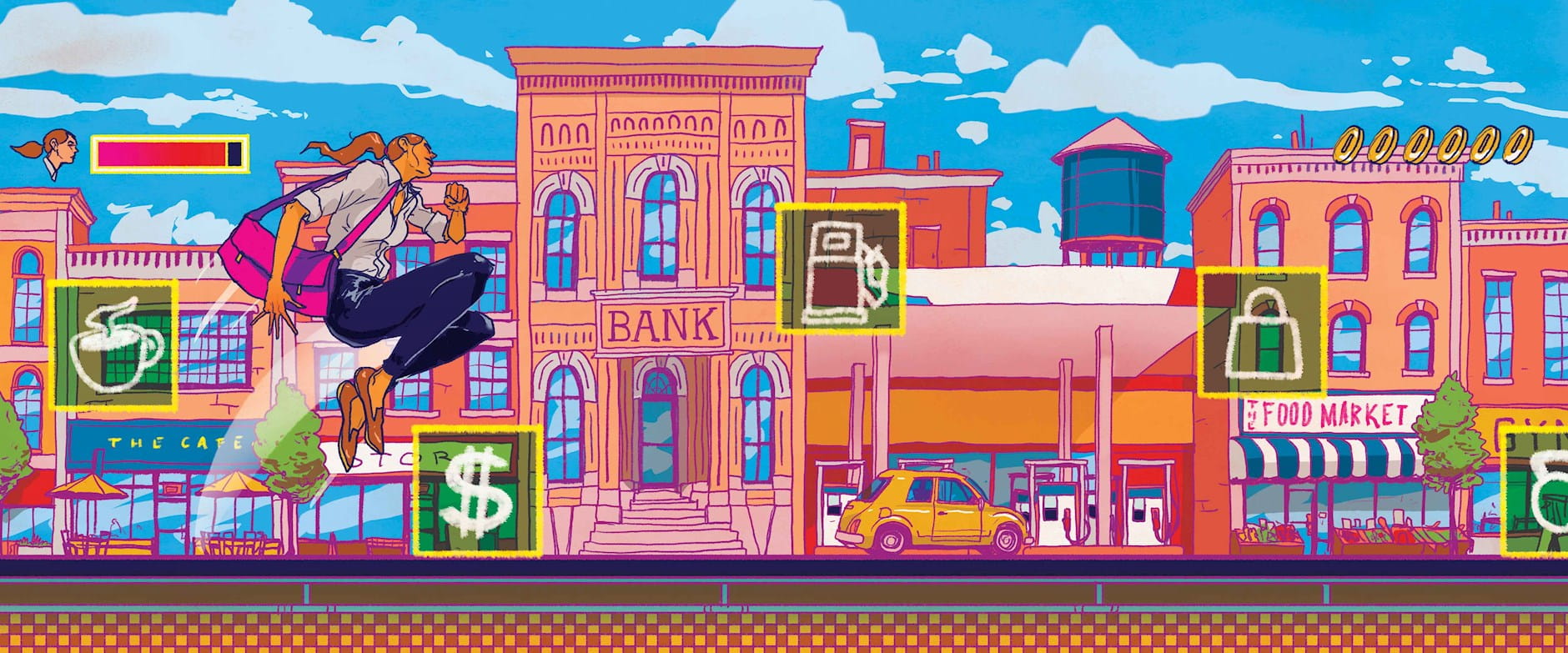

There are three ways to make a boring or difficult activity more intrinsically motivating. First, we have the aptly named “make-it-fun” strategy, which as you might guess involves making an activity fun. The make-it-fun strategy actively associates immediate incentives (i.e., minigoals) with pursuing the activity. These incentives harness our need for instant gratification and thereby make a previously dull activity more exciting, letting us experience it as its own end. For example, when Cornell’s Kaitlin Woolley and I (to the chagrin of some teachers) encouraged high-school math students to listen to music, eat snacks, and use brightly colored pens while doing their math assignment, we found that the students worked longer. Doing math was fun because it delivered immediate auditory, taste, and visual benefits. Catching a Pokémon is also an immediate incentive for Pokémon GO players.

Gym goers who chose a weight-lifting exercise they enjoyed completed about 50 percent more repetitions than those who chose an exercise they thought would be most effective.

People frequently apply this principle to make it fun when they bundle goals with temptations. Associating completing a workout with watching TV or working on a school assignment with listening to music is what’s known as temptation bundling. This strategy is particularly effective if you limit yourself to engaging in the tempting activity only while pursuing the goal. So, for example, you only let yourself eat a square of chocolate while answering your many work emails. Incorporating these temptations increases intrinsic motivation to pursue your goals. It’s critical, however, that the rewards are immediate. Adding a delayed reward, such as earning five squares of chocolate by the end of the workweek, won’t work.

The second strategy in the motivation-science tool kit is to find a fun path. When you set a goal and have to think about the path you’ll take to get there, factor in immediate enjoyment. For example, people who want to exercise more should consider finding workouts that sound fun. Rather than slogging away on a bike at the gym, try a spin class that uses upbeat music to keep you engaged. For people who like metal, some New York City spin studios offer “Death Cycle” classes in which instructors blast metal music while everyone works out. This is an effective strategy. As Woolley and I found in a study, gym goers who chose a weight-lifting exercise they enjoyed completed about 50 percent more repetitions than those who chose an exercise they thought would be most effective. Of course, you do still have to choose an activity that will ultimately help you accomplish your goal. If you’re exercising to get fit, low-impact yoga probably won’t help much. But when you have a set of activities that will accomplish the same goal, try to choose the one you’ll find most fun.

The third strategy is to notice the fun that already exists. If you focus on the immediate rather than delayed benefits for pursuing an activity, you’ll likely feel more intrinsically motivated and therefore be more likely to keep at it. Imagine you want to eat more carrots. If you focus on what you like about eating carrots—they’re crunchy, sweet, and a little earthy—rather than the fact that carrots are a healthy snack or the idea that they might improve your eyesight, you’ll be more likely to eat them. This is just what Woolley and I found in a study when we had people choose between two identical bags of baby carrots. We asked some people to choose the tastier-looking bag and some the healthier-looking bag. People ate almost 50 percent more when asked to choose the bag of carrots that looked tastier. Simply directing your attention to the immediate positive experience—to the extent that it exists—when making a choice will help you stick to your goals.

Ayelet Fishbach is the Jeffrey Breakenridge Keller Professor of Behavioral Science and Marketing and an IBM Corporation Faculty Scholar at Chicago Booth. Excerpted from GET IT DONE, reprinted by arrangement with Little, Brown Spark, a division of Hachette Book Group. Copyright © Ayelet Fishbach

- Kaitlin Woolley and Ayelet Fishbach, “It’s about Time: Earlier Rewards Increase Intrinsic Motivation,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, June 2018.

- ------, “For the Fun of It: Harnessing Immediate Rewards to Increase Persistence on Long-Term Goals,” Journal of Consumer Research, February 2016.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.