Ken Langone’s new book I Love Capitalism! An American Story might just as well be titled The Kids Are Not All Right. For years, publishers courted the founder of Home Depot to pen a memoir, but it was only after the 2016 presidential election that he finally accepted the invitation. The reason? “When I saw the massive number of young people gravitating toward Bernie Sanders,” the 82-year-old billionaire told an interviewer in May, “it scared the hell out of me.”

A self-proclaimed cheerleader for capitalism, Langone has every right to be worried. A spring 2016 poll from Harvard University’s Institute of Politics finds that only 19 percent of Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 identified themselves as capitalists, and 51 percent of those surveyed said they did not support capitalism. Similarly, a YouGov poll commissioned late last fall finds that, by 44 percent to 42 percent, more US millennials would rather live in a socialist country than a capitalist one, an ideological defeat for free marketeers that grows more ominous when the 7 percent who prefer communism are included.

Like Langone, I’m surprised by these findings. Unlike Langone, it’s because I wouldn’t have imagined capitalism to be nearly so popular among millennials.

As a demographic group, millennials fill the unruly club car that follows right behind my cohort, Generation X. Once the object of sustained curiosity but now something of a forgotten class, Gen Xers came of age in the 1990s, when the fall of Communism, the dot-com explosion, and galloping economic growth saw entrepreneurs, CEOs, and wizards of high finance become popular icons of American exceptionalism. With the tinsel shimmer of Hollywood celebrities and the aura of C-suite sages, this elite class of business professionals passed from relative anonymity to a steady rotation on cable television, in Executive Branch offices, and on tony panels at Aspen. These high-profile figures were tribunes of an unapologetic capitalism, hale and hopeful, without either the misgivings or the suspicions of extreme success.

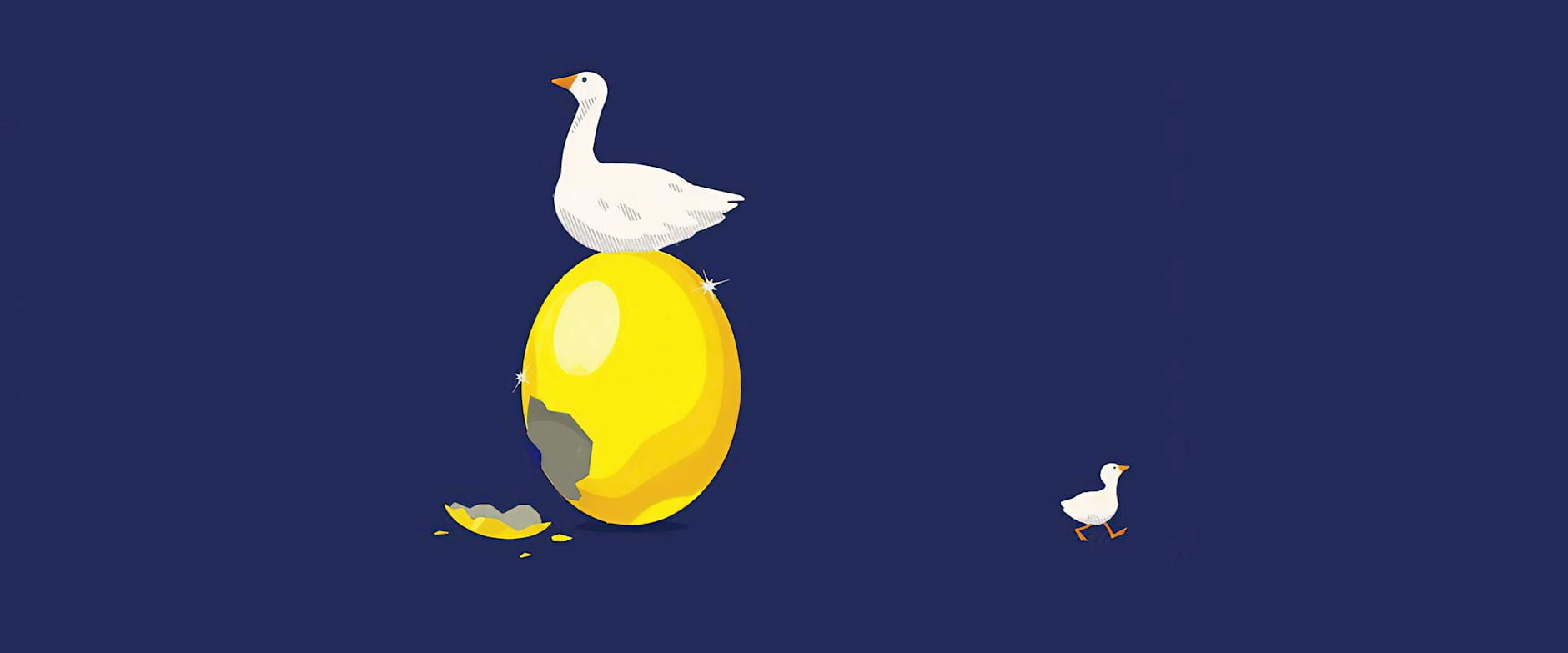

Economic arrangements will always be disputable, so capitalism was not without controversy even in this most remarkable decade. Still, with the evolution of capital markets, the efficiency gains brought about by information technology, and a boom in global trade, many of the most intense arguments about the economy revolved around how little the government could do in light of a golden goose that seemed so procreant with its eggs. Even the occasional reminders that capitalism retained the capacity for calamity—the Asian Financial Crisis, runaway inflation in Russia, the collapse of hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management—were swiftly dismissed as a necessary scolding of the invisible hand or evidence of creative destruction. Indeed, when US Secretary of the Treasury Robert Rubin, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, and US Deputy Secretary of the Treasury Larry Summers famously appeared on a 1999 cover of Time Magazine above the headline “The Committee to Save the World,” I suspect that many Gen Xers had the same thought I did: Really, the world needs saving?

Loosely defined as a cohort born sometime between the early 1980s and the late ’90s, millennials are a group whose historical consciousness was inaugurated by the horrors of 9/11 and the abrupt conclusion of so many comforting fictions that buoyed the irrational exuberance of the previous decade. Among these fantasies was the notion that American capitalism had effectively solved the problem of dissatisfied customers. Such a determination was less a direct response to the rock-bottom unemployment of the late 1990s or even five years of robust GDP growth north of 4 percent, and instead a general sense that capitalism was healthy, working well, and admirably fair to all parties. Certainly, most people arrived at such conclusions without recourse to much in the way of hard logic or rigorous analysis. Rather—like Langone’s declaration at the opening of his book, “Capitalism works. Let me say it again: It works!”—they were expressions of lived experience and a very personal faith.

Millennials have a limited faith in capitalism, and almost none at all in the financial sector. The same 2016 Harvard poll finds that only 11 percent of this particular group trusted Wall Street to do the right thing “most of the time,” a number that shrinks to 2 percent when “all of the time” is surveyed. Such results are hardly surprising if you consider the fact that the defining economic event for Americans 18–29 (the age range of those polled) is the 2007–10 financial crisis. If years of stagnant wages and sluggish growth, to say nothing of the economic effects of two ongoing wars, did little to create an economic environment where one felt particularly hopeful before the crisis, the “once-in-a-century credit tsunami,” as Alan Greenspan famously dubbed it, seemed to guarantee a generation of skeptics.

Having taught business ethics for more than a dozen years, I have seen the change in my own students. I began with classes filled with fellow Gen Xers and am now surrounded by millennials. A decade ago, memories of the dot-com implosion in addition to the spectacular case studies in corporate malfeasance of Enron, WorldCom, and Tyco tempered the fullest sense of capitalist triumphalism. However, for the most part, my rosters swelled with young professionals ebullient about the system they were preparing to lead. Today, few of my MBAs are explicitly anticapitalist—though, this year, I did have my first unapologetic socialist—but increasingly I find support for the system among my students to be lackluster and provisional. “Yeah, I guess capitalism is the best,” these students glumly convey in class discussion. “But there are a lot of problems with the system, and I really wish we could do better.”

This lack of faith in the capitalist system is the most far-reaching consequence of the financial crisis and the recession that followed.

Such reservations are reminiscent of John Maynard Keynes, who, a century ago, wrestled with the experience of the First World War and its implications for the moral psychology of capitalism. In the book that first brought him fame, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, Keynes described prewar conditions in Europe as a kind of “economic Utopia” that would have astounded earlier economists. Yes, he said, most people still “worked hard and lived at a low standard of comfort,” but with vivid improvements to material conditions in the memories of most adults, the working classes “were, to all appearances, reasonably contented.” Furthermore, “escape was possible for any man of capacity or character at all exceeding the average, into the middle and upper classes,” and to that most fortunate group “life offered, at a low cost and with the least trouble, conveniences, comforts, and amenities beyond the compass of the richest and most powerful monarchs of other ages.”

The corporeal consolations of capitalism were nothing to sniff at, Keynes granted, but they were also supported by a kind of ideological peace of mind. Before the fateful summer of 1914, he claimed, the “internationalization” of “social and economic life” was “nearly complete.” Such a “state of affairs”—an almost frictionless transit of people and goods across international boundary lines—seemed extraordinary in hindsight, but, according to Keynes, the affluent classes regarded them as “normal, certain, and permanent, except in the direction of further improvement” and any “deviation” as “aberrant, scandalous, and avoidable.”

Thus, for Keynes, the engine of global capitalism was humming along so merrily that most people assumed its wonder workings were akin to heavenly bodies: a revolutionary movement at once irresistible, astonishing, and ordinary. Significantly, while the forces of internationalization improved the material fortunes of Europe, the benefits were disbursed inequitably, and Keynes contended that the system was largely preserved from sabotage or even skepticism by what he called “a double bluff or deception.” For rich and poor alike, the spirit of capitalism was to endeavor to increase the size of the economic “cake” without ever enjoying more than a morsel or two of its deliciousness. For the poor, that meant working hard without much in the way of recompense but also without complaint, while for the rich it meant living by the mantra: reinvest every penny you make.

For Keynes, such material self-restraint did not survive the Great War, which largely shattered the ideological peace of mind that supported such behavior. The war laid bare the fact that the conditions that defined internationalization were both fragile and unlikely. At the same time, insofar as the industrialized nations had organized unprecedented resources and manpower not for purposes of building a better future but for staging a four-year orgy of ritual destruction, the First World War had “disclosed the possibility of consumption to all and the vanity of abstinence to many.” The double bluff was revealed. The “laboring classes may be no longer willing to forgo so largely,” Keynes predicted of postwar Europe, “and the capitalist classes, no longer confident of the future, may seek to enjoy more fully their liberties of consumption so long as they last.”

A decade after the collapse of Lehman Brothers paralyzed the financial system and provoked the US government into what effectively became a multiyear, multitrillion-dollar intervention, the same ideological peace of mind that once underwrote the policies of globalization seems, to many, like a utopian dream or a diabolical enchantment, depending on one’s politics. Millennials apparently lean toward the latter assessment, less pessimistic about the possibilities of free-market capitalism than about the worthiness of its practice. This lack of faith in the capitalist system is the most far-reaching consequence of the financial crisis and the recession that followed, and, in many respects, the only thing surprising about such doubts is they took so long to blossom.

The justification for extraordinary intervention by the federal government to address the crisis had the infuriating logic of a hostage taker threatening to shoot himself.

For more than two decades before the crisis, the US economy had maintained an uneasy peace between the cultural consequences of capitalism and its democratic promise. Beginning in the “greed is good” 1980s, the wealthy began dispensing with the appearance of modesty, preferring to embody a caricature from The Bonfire of the Vanities rather than even pay lip service to old money’s self-restraint. Moreover, by failing to acknowledge the prevailing norms regarding conspicuous consumption, they at once changed those norms and made themselves far more conspicuous.

Such excess could be tolerated as long as the success of the financial elite led to the material benefit of the broader public. No one especially likes the accomplishments of another to be rubbed in his face, but he is more willing to tolerate the affront to his pride if his pocketbook swells for his patience. Americans could comfort themselves with this belief throughout much of the 1980s and ’90s, but by the first stirrings of the crisis in 2007, this causal assumption, so integral to a faith in capitalism, had begun to fray. In popular terms, the rich seemed to be getting richer without the rest having much to show for it.

That Wall Street became the epicenter of the crisis was a significant blow to this flagging faith. To the masses, financiers have always had trouble accounting for outsized success. Henry Ford could point to a nation of Model Ts, Bill Gates an empire of Windows, but the billionaire hedge-fund manager or chieftain of an investment bank must contend that the grease he applies to the gears of the economy entitles him to a prime slice of Keynes’s cake. Few Americans found such arguments compelling even before the crisis. Indeed, they seemed to regard most everyone in finance in the same light as they viewed high-stakes poker players in Las Vegas. The moral benison of their craft was doubtful, but as long as they didn’t crow too loudly about their winnings, they could be left to play cards at the corner table, endlessly passing chips.

The enduring ideological problem for American capitalism was not the revelation that when everyone at the corner table lost after going all in, it affected the odds of everyone else at the casino. Nor was it that the house would have to borrow chips from the rest of the patrons to ensure the high rollers could keep playing. Rather, it was that the justification for extraordinary intervention by the federal government to address the crisis had the infuriating logic of a hostage taker threatening to shoot himself. As Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein phrased it in fall 2009, “If the financial system goes down, our business is going down and, trust me, yours and everyone else’s is going down too.”

In other words, if we can’t keep playing cards, everyone in the casino will end up losing their shirts.

Whatever the merits of such intervention as economic policy, morally speaking, it has always been bankrupt. At the same time, because exceptional measures were not also taken to insulate average Americans from the secondary effects of the subprime debacle and the ensuing credit crisis, it seemed as if those who were most capable of surviving the crisis without jeopardizing their ability to make ends meet were insured against their mistakes, while others who were far more vulnerable, and far less culpable, if at all, for what had happened, were barely

an afterthought.

The rise of social media during this time helped inflame the discontent around the disparity between these fates, affording an endless string of images and commentary to sharpen its moral, social, and political significance. Indeed, 10 years after the frantic autumn of 2008, after a decade where the economy averaged less than 1.5 percent annual growth while the wealthiest Americans claimed an ever larger slice of Keynes’s cake, can it be at all surprising that millennials could tell pollsters in the YouGov survey above that a majority of them believed that “the American free enterprise system worked against them”?

Langone, of course, tells a different story. “[I]f there’s one lesson I could pass along to kids today,” he says near the end of I Love Capitalism! “it’s this: the opportunities in America today are the very best they’ve ever been.” Whether or not there is good reason to believe him is somewhat beside the point. As Keynes understood, the stories we tell ourselves about capitalism are always moral assessments of lived experience, and they tend to be powerful omens of economic prophecy.

A decade after the crisis, the story most young Americans tell themselves about capitalism hardly gives them good reason for faith. Langone, and others like him, are right to be worried about the system they love. Frankly, they should be terrified.

John Paul Rollert is adjunct assistant professor of behavioral science at Chicago Booth.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.