Does Extending Jobless Benefits Help in a Recession?

- By

- May 08, 2020

- CBR - Economics

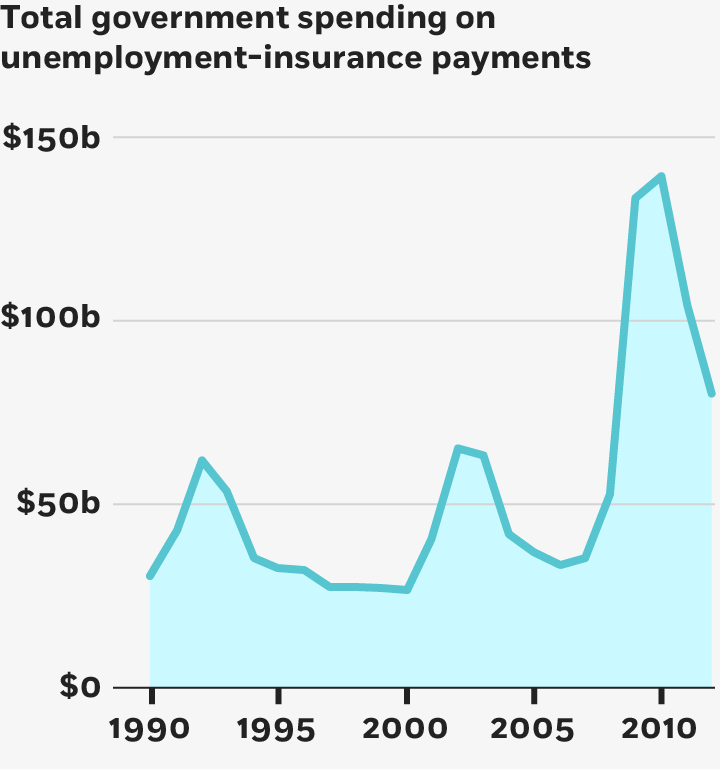

One of the first things US Congress usually does in a recession is extend unemployment benefits. Lawmakers did so in 2008 as the Great Recession unfolded and again in 2020 as the COVID-19 crisis hit. It’s an application of a long-standing economic theory that such payments help support consumption and partially counter downward cycles.

But do the data support this theory? There’s been little empirical evidence, and the answer depends on whether people collecting the money turn around and spend it, according to Cornerstone Research’s Graham McKee and MIT’s Emil Verner. But their study of what happened when the government distributed $237 billion to jobless people from 2008 through 2012 indicates that the theory may match what happens in the real world.

McKee and Verner analyzed detailed consumption data for 2007–12 from the Nielsen Consumer Panel, a survey of 40,000–60,000 households across the United States that’s part of the Nielsen Datasets at Chicago Booth’s Kilts Center for Marketing. The households in the panel use barcode scanners to record purchases from shopping trips. The data also capture demographic information, including employment status.

Increase in unemployment benefits during 2008–09 crisis

McKee and Verner, 2015

Over 2008–09, Congress took a series of steps that extended unemployment benefits from 26 weeks to as many as 99 weeks. Lawmakers also expanded federal subsidies to states from 50 percent to 100 percent. Each US state administers its own unemployment program.

Because the Great Recession hit some states harder than others, many of them didn’t meet the unemployment-rate thresholds that triggered the full extension of benefits. The researchers exploited this difference to calculate the economic effects of each additional week of jobless payments.

Recipients plowed most of the money right back into the economy, the researchers find. One extra week of unemployment benefits increased household spending by 1.7 percent, or more than $172 over six months. McKee and Verner calculate that for each $1 of unemployment benefits, household spending rose by 59–91 cents. This compares with 20–40 cents of added consumption for each $1 of tax rebates, as found by University of Chicago’s Greg Kaplan and Princeton’s Giovanni L. Violante.

Applying these estimates to total government outlays for jobless benefits in 2010, McKee and Verner calculate a direct increase in consumption of $46.5 billion–$71.9 billion, or between a third and a half percentage points of GDP.

“We interpret this as evidence in favor of the hypothesis that unemployed households are particularly responsive to transitory income transfers, as these households typically have temporarily depressed income and low liquid wealth,” the researchers write. “This large consumption response to an additional week of benefits suggests that expanding UI [unemployment insurance] in a recession is an effective policy tool for boosting private spending in a timely and transitory manner.”

The findings may provide some reassurance for policy makers trying to address the current contraction, which may be the deepest since the Great Depression. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act extends and dramatically expands jobless relief by an estimated $260 billion over just the next few months.

In addition to one-time direct-relief payments of $1,200 to most people, the measure expands eligibility for unemployment compensation to the self-employed and independent contractors, who normally don’t qualify. It also extends benefits from the normal 26 weeks to 39 and adds $600 a week through July 31 to the national average jobless benefit of $385 a week. The research suggests that some elements of the CARES Act will have the desired effect of bolstering consumer spending, the main driver of the US economy.

- Greg Kaplan and Giovanni L. Violante, “A Model of the Consumption Response to Fiscal Stimulus Payments,” Econometrica, July 2014.

- Graham McKee and Emil Verner, “The Consumption Response to Extended Unemployment Benefits in the Great Recession,” Working paper, July 2015.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.