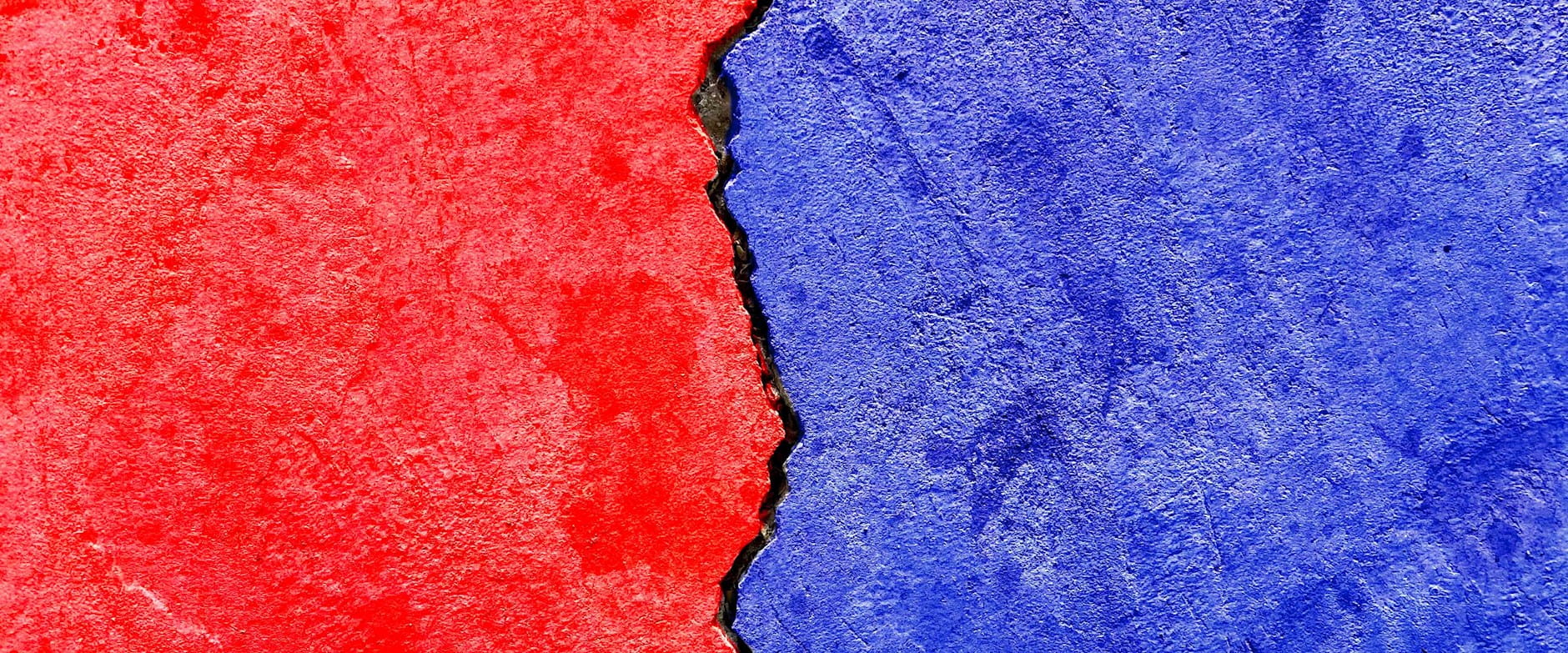

Increased polarization in the United States has meant more political homogeneity across digital, social, and civic spaces. But what about workplaces, where so many Americans spend so much of their time? Chicago Booth’s Elisabeth Kempf has research looking at political alignment within corporate executive teams, and whether or how much it has increased over time. On this episode of the Capitalisn’t podcast, hosts Luigi Zingales and Bethany McLean sit down with Kempf to understand the factors that could be influencing this trend, legal structures that may or may not protect against discrimination based on political views, executive departures that may be politically motivated, and why we might care about political diversity in the workplace at all.

Elisabeth Kempf: The workplace actually plays quite an important political and social role, in the sense that it exposes us to views from the other party, much more so than, for example, our families or our neighborhoods or our social clubs. So, in that sense, yes, when you have more homogeneous workplaces, it means you’re really diminishing these opportunities for cross-party interactions.

Bethany: I’m Bethany McLean.

Phil Donahue: Did you ever have a moment of doubt about capitalism and whether greed’s a good idea?

Luigi: And I’m Luigi Zingales.

Bernie Sanders: We have socialism for the very rich, rugged individualism for the poor.

Bethany: And this is Capitalisn’t, a podcast about what is working in capitalism.

Milton Friedman: First of all, tell me, is there some society you know that doesn’t run on greed?

Luigi: And, most importantly, what isn’t.

Warren Buffett: We ought to do better by the people that get left behind. I don’t think we should kill the capitalist system in the process.

Bethany: Increased polarization in America means more homogeneity in political views among our friends, family, and, of course, on social media. Once upon a time, we might not have married someone of a different religion or mixed and matched at a dinner party.

Now, as a friend of mine who is Jewish, said to me recently, “I wouldn’t mind if my children married Gentiles, but I’d disown them if they married Republican.” This all raises a question. What about our workplaces where so many Americans spend the bulk of their time? Are they homogeneous, too? And if so, does that matter?

Here to discuss this with us is Associate Professor of Finance at Chicago Booth Elisabeth Kempf, who has just published some fascinating new research studying how political homogeneity within corporate executive teams has manifested over time and whether it’s increased.

So, Elisabeth, tell us about this research. What led you to do it?

Elisabeth Kempf: I generally got fascinated and interested in the topic of political polarization after seeing growing cross-party hostility between Democrats and Republicans. How does this affect firms and the economy more broadly?

In previous work, we looked at to what extent alignment with the president affects our optimism about the economy. And, in that particular case, we were looking at financial analysts, and we saw that they are much more optimistic when their own party is in power than when it’s not.

So, the fact that there are these individual partisan biases means that studying homogeneity in the workplace is important, because if the workplace is becoming more homogeneous, then we don’t have a Republican and a Democrat discussing and landing somewhere in the middle, but they’re increasingly surrounded in a bubble.

And, in this particular paper, we’re looking at executive teams. We wanted to see whether it is true that also there, Democrats cluster more with Democrats, and Republicans cluster more with Republicans.

Luigi: Let me play the devil’s advocate a little bit here, because you have a very precise measure of similarity. So, you say the probability that two executives are from the same party. If you randomly draw them, what is the probability that they come up from the same party? And you come up with something like 78 percent. But when you look at gender, the probability is 89 percent. And when you look at ethnicity, it is 95.5 percent. So, it’s a problem, but gender and ethnicity or race seems to be much bigger.

Elisabeth Kempf: There’s certainly two distinctions. One, when we talk about the level of homogeneity, you’re absolutely right. When we’re looking at race and gender, we see a higher level of homogeneity. It’s a fact that there’s few women and few minorities in the executive suite. But what I think is interesting is that when you look at the trends, at least we’re moving in the direction of teams becoming more diverse.

I would have thought that, if anything, that should mean that we should also get more political diversity in executive teams, but it seems that political diversity is moving exactly in the opposite direction and, actually, very strongly so, and we thought this is very interesting and important to document.

Bethany: I agree with that, Luigi, and I’d push back a little bit on your devil’s advocate pushback, which is that I think the fact that it is going in the opposite direction when other measures of diversity are increasing is really interesting and really telling. I was also, I have to admit, a little bit surprised that even though homogeneity is increasing, that it was already very high to begin with. I think I saw the numbers in your paper that in 2008, 75 percent of companies had executive teams that were quite homogeneous.

I’m getting screwed up with homogeneous and homogeneity. It’s very difficult to keep saying these words. And that that number had increased to 80 percent by 2018. Which is an increase, but still, that it was 75 percent already seems to say that this has been a problem for a while.

Elisabeth Kempf: And I think, also, here what we found was that the level of political homogeneity is actually higher than what you would have expected based on, for example, political contributions. So, if we look at political donations, it looks more balanced generally. The executive population as a whole is more like 60 percent Republicans, 40 percent Democrats.

When you look at the voter-registration data, which is what we’re using in this paper, and we’re arguing that voter-registration data give you a cleaner measure of the executive’s ideology than the donations, you see that they are actually more homogeneous. So, we’re talking more 70 percent Republican, 30 percent Democrat. So that, of course, leads to the fact that we’re already looking at a pretty high level of homogeneity among these executives.

Bethany: Proof of crony capitalism, or proof of the cynicism of corporate America, that the political contributions are quite even? They’re happy to give money to both causes, but that doesn’t actually reflect their beliefs.

Elisabeth Kempf: The other thing that’s interesting is that when you look at the time trends also in contributions, you see some differences. For example, the Democratic executives are increasingly giving to the Democratic Party, which we thought is consistent with the perception that many have that maybe executives have become more outspoken on progressive issues or are more openly Democrat. Certainly, when you look at the contribution, that seems to be the case. But it’s not really driven by there being more Democrat executives. It just seems to be that the Democrats that are there are just increasingly giving to the Democratic Party compared to 2008.

Luigi: To what extent is this phenomenon of polarization specific to firms and to what extent does it reflect the society at large? Because, at the end of the day, if you have a firm in Texas, probably most of the executives are going to be Republicans. And if you have it in Silicon Valley, most of the executives would be Democrats. But if you go outside of the headquarters, in Texas, they’re even more homogeneously Republican, and probably in Silicon Valley even more homogeneously Democrat. To what extent is this specific to firms, and to what extent is it just a reflection of society?

Elisabeth Kempf: We do think that it is also a reflection of the broader society, and we do see that, for example, a lot of the increase in this homogeneity is coming from increased sorting by executives into specific locations. So, what I mean by that is executives in Texas becoming more Republican and executives in California becoming more Democrat. That seems to be explaining a lot of the aggregate trend. That said, we see that even within locations and within the same firms, there seems to be sorting going on based on political affiliations.

Bethany: In a way, it’s almost self-perpetuating in the sense of a broader polarization, in the sense that executives are increasingly living and taking their families to the places that reflect their political beliefs.

Elisabeth Kempf: Yeah.

Bethany: So, that’s actually driving polarization in the rest of society, too. At least if you view it—and I’m not actually sure this is right—but if you view business as a driver of mobility, then you’re actually creating a weirdly vicious circle here, in a sense.

Elisabeth Kempf: Yes, it is. And you could see this perpetuate, in that the workplace actually plays quite an important political and social role, in the sense that it exposes us to views from the other party much more so than, for example, our families or our neighborhoods or our social clubs. So, in that sense, yes, when you have more homogeneous workplaces, it means you’re really diminishing these opportunities for cross-party interactions.

Luigi: So, how do you interpret this? Is this that inside firms, people are shunned if they don’t agree or that you don’t get promoted if you don’t share the same political views? What is the mechanism?

Elisabeth Kempf: We do see that the sorting that we see within firms is indeed driven by this growing friction between Democrats and Republicans that they might not just get along, even in the workplace. So, the evidence that we have for that is we looked at executive departures, and we find that executives whose ideology does not match the majority of the team are more likely to leave. And that’s especially true in most recent years. So, when you look at 2015 and later.

On top of that, we kind of looked at, is that effect more pronounced for executives that are more political? And the nice thing is, we have some proxies for the strength of their political beliefs, like how frequently do they vote? Do they agree with their spouse? The idea was if you’re married to somebody from the other party, maybe you can work with somebody from the other party. And all those proxies for strength of political beliefs seem to suggest that it’s the stronger the political beliefs, the more likely you are to leave a team where you don’t fit in, in terms of your political ideology.

Luigi: And this is the reason why your paper comes very apropos, because in the last episode we interviewed Vivek Ramaswamy, who was basically forced to leave by his employees because he had a very strong political view which differed from the rest of the firm. So, he’s exhibit A of your paper.

Elisabeth Kempf: That’s good to know, to have another data point.

Bethany: Speaking of the episode with Vivek, he argues that wokeness is essentially destroying capitalism, and I was actually surprised by what I thought was some contradictory data in your paper, although I may have misread it, which is that there actually is an increasing share of Republican executives. So, not only do you see increased polarization, but you see increased Republicanism in executives, which would seem to point in the opposite direction of wokeness taking over corporate America. Unless the hypocrisy is just exploding everywhere.

Elisabeth Kempf: We’re looking at the executive level. At least at the executive level, it’s true that in particular, between 2008 and 2012, the share of Republican executives has increased. Since then, it has hovered pretty steadily around the 70 percent threshold. It suggests that, at least when you’re looking at their ideology, there hasn’t been a shift towards more Democratic executives. However, we do see this effect on the contributions, so they seem to be more openly in favor of the Democratic Party.

Bethany: One of the other overlays I think you did was to look at the difference in states that have laws prohibiting discrimination based on political beliefs. What showed up there? Are laws effective? Can you enforce this, or is it a more subtle thing that happens in quiet conversations where you just realize you don’t fit in, much as other problems with diversity have always been? They sort of escape the attempts at policing them, is what I’m getting at. And I wonder if that’s true here, too.

Elisabeth Kempf: There’s no federal law in the US that prohibits political discrimination by private employers. But you’re absolutely right that there are several states that have passed laws that restrict the degree to which private employers can punish their employees or maybe refuse to hire employees whose political views they don’t agree with or they don’t like. And we see that the legal environment does matter. We see that the increase in homogeneity is larger in states that have not passed those laws, so essentially, where employers are not somewhat restricted to what extent they can hire, fire, based on political views.

Luigi: But your sample is a limited sample because of voter registration. When I look at the sample of people that you have with voter registration and the sample of states with a law protecting employees, there are very few states that are left out, so it’s very hard to tell whether it’s the law or some idiosyncratic element from those states.

Because, honestly, I can see the law working at a lower level in the administration, but the kind of discrimination that I think you’re talking about, correct me if I’m wrong, is not that I don’t hire you because you are Republican or Democrat, whatever. It is that I don’t invite you to the right party because I don’t like your position. As such, you’re less likely to be promoted to become a CEO or executive, and you feel less love in the place.

Elisabeth Kempf: No, you’re right that we’re not saying that the legal environment is all that matters or even a major factor in that. You’re also right that we only have voter-registration data for nine states. There’s three of them that haven’t passed such a law. So, you could, of course, tell some other story of what factors are different in those states. But it does suggest, at least, that it’s worth exploring in future research. And it’s certainly on our agenda to look more into to what extent these state-level laws matter, and where do they change the homogeneity? Maybe they change that at the lower level, but then it creeps into the higher ranks eventually as well.

So, we don’t think it’s the only factor that’s driving it, but it does show up very starkly in the sense that the increase in homogeneity is really much weaker in the states that have passed such laws.

Bethany: Your research concluded before the pandemic, but I’m wondering if you guys have thought about it or if you’re going to do a follow-up as to what happens when you see this shift of companies that were very much blue-state companies, like Silicon Valley companies and a fair number of financial firms, moving to red states like Florida and Texas and how that ends up affecting homogeneity.

Elisabeth Kempf: You could imagine that maybe it shifts the ideology of the executives that are then attracted to work in Texas, let’s say. But you could also imagine the causality the other way around, that the ideology of the executives determines which companies move. That the companies that move from California to Texas could be the ones where the executives would find the idea less disturbing to move to a very Republican place. So, that’s something that we haven’t explored yet, but we definitely want to do that in the future.

Luigi: I vote for the second, because I certainly know friends of mine that say, “I will never move to that state,” because their wives don’t want to be in an area that is too Republican, and so they stay in Illinois because of that. So, I can see executives not moving the firm because their spouses are not willing to move to Florida or Texas.

Elisabeth Kempf: And I think that’s also why we see that this geographical sorting can explain a lot of the increase in homogeneity, because I think the state is just very salient. We all immediately have some association when we’re thinking about California or Texas or New York in terms of the political leaning of that place. And, of course, within firms that might be less salient, or you really have to spend time with other executives in the firm to figure out, are they strong Republicans or strong Democrats?

Bethany: I realized as I asked questions that I do have a bias in this, that I think diversity is good, and I think diversity of all kinds of thoughts is good, including political diversity. And I realized I had not thought it through before, but I realized the framing with which I asked the questions implied that it’s good.

So, one of the things that has helped, I think, firms move in the right direction on other measures of diversity has been that it’s linked to performance. More diverse teams perform better. And that’s helped everybody say, “Aha, not only are we doing the right thing, but this is the right thing for our business as well.”

Are there any measures that do explore or can explore whether political homogeneity matters in terms of corporate performance?

Elisabeth Kempf: It’s a very difficult question to answer empirically. In the real world, we just never have these experiments. The most, which is more indirect evidence, that we have on this is we see that the increase in homogeneity is stronger in firms with stronger executives and weaker shareholders. For example, low institutional ownership or CEOs with longer tenure. So, that’s very indirect evidence, but it is kind of, at least, a bit suggestive, because if this were in the interest of shareholders, then you would expect more sophisticated shareholders like institutional investors would have figured that out. But it does not show up in these firms that are run by stronger shareholders.

Luigi: But the institutional-investor ownership is so large these days that probably the ones with low institutional ownership are the ones with a big stake by the incumbent CEO. So, if you are Amazon, you’re probably low institutional ownership because Bezos owns so much of it. It is not because of other considerations. To what extent is it that maybe founders have a strong culture? Some aspect of this culture might also be their political attitude.

Elisabeth Kempf: We haven’t separately looked at founders. I think that’s a great idea. We should look at that. So far we’ve really focused on . . . Sorry.

Bethany: We all have interruptions, don’t worry. My dogs are behaving right now. The children are maybe burning the house down, but the fire hasn’t reached me yet. Go ahead with your interruptions, it’s all good.

Elisabeth Kempf: I did put my phone on airplane mode, but I didn’t think of my office phone. Also, normally I never get calls on my office phone, ever. I think this is like the first time in months.

So, we haven’t looked at founders yet, but we have tried to look at firms where CEOs are more powerful, and CEOs with longer tenures would be one such proxy, and we see that it’s more pronounced in those firms, this increase in homogeneity.

That’s at least suggestive evidence that it might be coming from the executives rather than from the shareholders. But I really don’t want to push this point too much, because I think we definitely need more work on this to figure out, is this really in the financial interest of shareholders or not?

Luigi: I find it strange because, and I’m different than most people here, but I find that the difference between a Jeb Bush Republican and a Biden Democrat is not that big. Where you see the big variation is between the Trump Republican and the Bernie Sanders Democrat. I don’t know whether you tried or even if you could see whether you see kind of a variation also in that dimension. Because we know, for example, that open donations to Republicans have gone down, which I suspect are donations to Trump. So, I think that the executives are not particularly Trump supporters. I suspect they’re not even Bernie Sanders supporters.

Maybe it’s just much ado about nothing, about what is the marginal tax rate. Because the only difference between Biden and Jeb Bush is probably how much the highest marginal tax rate is. First of all, is that reasonable? And, two, can you try to disentangle this, maybe by looking at what type of candidates they donate money to? I understand you prefer registration, but I don’t think you know who they voted for in the registration. But the beauty of the donations is you know who they donated to.

Bethany: My turn. Apologies. My phone never rings, either. Keep going, please.

Elisabeth Kempf: Looking at the candidates they support with their political donations is something that we’re definitely planning to do. I would also expect them not to support the candidates at the extremes of the political spectrum. To your question, does it matter, or are they all so much in the center that it doesn’t really matter whether they’re Democrat or Republican? I think our departure result does suggest that if most of your other teammates are Democrat and you’re Republican or vice versa, that increases your chance of leaving. In that sense, it does . . . At least they’re not close enough that there is no disagreement at all, and so, then, we shouldn’t see the departure effect that we do see.

Luigi: No, I understand. But maybe they are departing about their food, if all the Republicans eat meat, and all the Democrats are vegetarians.

Bethany: Come on, Luigi.

Elisabeth Kempf: With the candidates, we might get at what potential issues could they disagree on? Which, right now, it’s very much a black box to us. What they disagree on could be a lot of things.

Bethany: I happen to love cheeseburgers. I’ll leave you to guess what my political affiliation is. Well, thank you. I think this is fascinating, and it’ll be interesting to see how the research progresses from here and what else you guys turn up.

Elisabeth Kempf: Thanks so much. And you had a lot of food for thought and things that we can look at in the future. So, thanks so much.

Luigi: I have to say, the impression I’ve gotten by reading the newspapers and also by seeing people like Vivek complaining so bitterly about woke corporate America is that, in recent years, there was a massive movement of companies becoming more and more “leftist” in their establishment.

Now, the data that Elisabeth has, the overwhelming number of companies tend to be Republican, so it’s 70/30. That’s kind of the split. So, there is not this overwhelmingly Democratic bias in corporate America. It might be that the more prestigious, or the more trendy, or the more valuable companies, because they tend to be in Silicon Valley, they tend to be all Democrat. That’s a different story. But that’s one factoid.

And the second is, I think that if there is enough competition, having companies with different political beliefs is not a problem. If you can pick and choose, and you don’t feel left out as a result, that’s not a big deal. It becomes much more a big deal if you are a monopolist, especially if you are a monopolist of information like Facebook or Google. Then that, I think, is an issue.

Bethany: I might disagree with your first point. Obviously, I agree Elisabeth’s data shows convincingly that corporate America is still extremely Republican, but I disagree that that means that the complaints about woke corporate America aren’t true. Both things can actually exist simultaneously. You can have a corporate America that actually does vote quite Republican, but that is putting on a veneer of wokeism in order to appeal to their younger employees, to create a marketing veneer for the world that has nothing to do with the truth of the company.

I’m not saying that is true simultaneously. You’d have to do quite a bit more analysis to know that if it was. But it’s actually possible that both things are true, that you have heavily Republican organizations that are nonetheless adopting the language of wokeism, because that’s what one does today. And that, to me, goes back to my point about the hypocrisy of campaign contributions. Despite the fact that firms are quite politicized, they give money very generously to both parties because of the pragmatism involved in doing so. That actually bugged me more than the fact that they are politicized.

Luigi: Ironically, the fact that they contribute to both sides suggests that at least if you are concerned about the partisan divide, Republican, Democrat, you shouldn’t be too concerned about corporate donations, because they’re not exactly equal, but they’re not that far off.

However, if you are concerned about capture by incumbents of our regulation and rules, then you should be very, very concerned, because then there is no opposition to capture, because whether you are Republican or Democrat, a company contributes to the same politicians to get the same outcomes that are not different between the two parties. And so, as a result, as a voter, you have no choice, you have no alternative.

I think, and I know this is a very unpopular position, but there’s too much these days about the divide between left and right or Republican and Democrat, and not enough about the distinction between corporatist and maybe populist. I think that that distinction is equally important.

Bethany: Maybe we need a third political party today. There’s Democrat, there’s Republican, and there’s corporatist, because corporatists—it’s a hard word to say—might argue for positions that are Democratic, that are Republican, that are neither, depending on . . . They argue for their own interests, for the interests of their executives and stakeholders.

My point about hypocrisy aside, I’m not sure which is more dangerous. What would you rather have? Would you rather have heavily Democratic companies always lobbying for the Democratic point of view and giving money to Democrats? Is that more or less dangerous than this corporatist viewpoint where it really is a mishmash, and it’s nothing, but it’s very powerful? In other words, it’s not defined in a Democratic or Republican way, and so we tend not to focus on it perhaps as much as we should, but it is quite influential, nonetheless.

Luigi: I would much prefer a world in which only one party gets the donations of all the corporations, because then you would have a way to vote for the opponents, and you know that the opponents are clean. If both are equally in bed with the parties, you don’t have a choice to change things. And I think that’s the problem.

Bethany: I actually think the point she’s making in the paper and in our conversation is that it is highly, highly relevant, because people spend the majority of their time at work, or at least they did. Maybe that’s changed in the era of Zoom. But that work is the place where you could encounter somebody with a different point of view, and that may shape your thinking, and then that new thinking may be something that you bring home or may be something that you bring out to your next social gathering with previously completely like-minded friends.

I think her argument is less that the political polarization in the workplace matters for what companies do and what they don’t do, it’s that it matters for what we all do, and how we all live, and how we all think. Because if you’re primarily around people in your workplace who also think the same way you do, then one of the major opportunities for you to change your mind or broaden your thinking is gone.

Luigi: But let’s not overextend the findings, because the findings are about the three or four top executives of every firm. We’re not talking about the rank and file, and maybe it’s the same for the rank and file, but I think the paper cannot address that question. So, first of all, you want people that have a passion for a business. Today, how could they have a passion for the oil business if you are a Democrat? It’s kind of difficult because climate change is—

Bethany: Actually, I’m going to argue with you on that.

Luigi: No, but it’s true. I think that it’s very difficult to have a passion for oil and at the same time be concerned about climate change.

Bethany: I’m arguing for the sake of playing devil’s advocate, because I do think this gets at one of the broader issues that we’re discussing. Yes, broadly speaking, I agree. Except, more narrowly speaking, there is an argument out there that the passion for climate-change policies is a mark in and of itself—and this isn’t always true—but of the economic elite, because right now, fuel prices are going through the roof. Guess who that affects, mostly?

It affects the not-so-well-off, for whom the dramatic change in what they pay at the pump can mean the difference between being able to feed their families well and not being able to feed a family well. Energy is one of the things that has transformed economies around the globe, lifted them out of poverty, given people a chance at a better lifestyle.

For economic elites to say, “We got our energy, and now you can live without it,” it’s a very elite position in some ways, and I say that while not minimizing at all the effects of climate change and the fact that we have to deal with it. But I think it’s possible to hold these two truths at the same time. One is that this is a terrible crisis that we have to deal with, and the other is that dealing with it by not financing any oil and gas anymore is going to disproportionately hurt the very people we all say we care about.

Luigi: I think we should postpone the discussion of climate change to a separate podcast. I don’t necessarily disagree with you that it is an elite position. But remember, we’re talking now about elites, we’re talking about the top executives. And I’m not saying that if you are an enlightened Democrat, you want to bring oil to zero. But it’s very difficult to have a passion for the oil industry in the way many oil executives have if you are super concerned about climate change. And I think that, on the other hand, it’s more difficult to be very passionate about certain businesses if you are a very conservative Republican.

So, I think that there might be some association between your ability to be gung-ho about a sector and your political views. I don’t think that that would be that surprising. What I thought was more interesting, in a previous paper by Elisabeth, is that, even in the same industry, you might see differences.

She noticed this difference between the composition of executives at Moody’s and the composition of executives at Standard & Poor’s, actually, not only the executives there, the credit analysts. If I remember correctly, Moody’s is more Republican and Standard & Poor’s is more Democrat, and these are two companies in the same business, and that I find it much more intriguing.

Bethany: And that would be a very interesting micro case study of this. Do people who want to work at the credit-rating agencies understand that dynamic and choose to go to Moody’s or choose to go to S&P because of their preexisting political beliefs? And that would be a very interesting further bit of insight, if that’s actually true.

Luigi: But also, I am not an expert in managerial science, but what I understand is that it is important to have some element that binds people together. A lot of them are social activities you do together. So, if you are in a group that has recreational activity, goes to hunt, and that’s the kind of fun, it’s very different than the ones that want to go to do yoga, and they are vegan. I think that’s a very different environment. So, you don’t need to sort on political views, but if you are a hunter and you find yourself in a group of vegans who do yoga, I don’t think you last very long.

Bethany: That’s actually depressing, because then your argument is further in service of Elisabeth’s, and that it’s increasingly hard to find places where you may encounter different points of view, even if you simply sort yourself by activities you like. I was thinking something slightly different when you started going back to Elisabeth’s point about the workplace being where we spend most of our time. Which is, there’s also research, I think, showing that one of the things that will get people to change their minds about a deeply held belief is if somebody they really respect offers a slightly different take on it.

And so, you can see this furthering itself in really damaging ways, in the sense that if we do spend all our time at work, the person who might come back from work thinking about something a little bit differently and then share it with their social circle, thereby, like the wings of a butterfly or dropping a stone into a pond and seeing the ripples go out, and therefore that slightly changed point of view might affect all the people in their group. We’re losing the opportunities for that.

And then, per your point, all of your social activities sort by political ideology. I’m not sure I’m going to give you that. I think there are Democrats who like to hunt. I think there are Democrats who are not vegan. I think there are Democrats who like cheeseburgers. I think there might—

Luigi: How many Republicans are vegan?

Bethany: I think there might even be some vegan Republicans, there might even be some yoga-doing Republicans. I don’t know. Maybe these things are unicorns. Maybe they’re not. I’m not sure.

Luigi: The other point that we have not touched, which I think is important, is we shouldn’t complain too much about companies, because if we look around our environments, i.e., academia and the world of news, I think they are probably much more polarized and, actually, disproportionate on one side than the other.

I was looking at donations after 2016, and I think that there were no faculty at the University of Chicago who donated to Trump and in the entire Harvard University, there was one faculty member who donated to Trump. Now, not all Republicans donated to Trump, not even all Republicans voted for Trump, but I think it gives you a sense of the disproportion in academia. And I think the world of the news, unless you go to Breitbart, is pretty much the same way.

Bethany: It’s funny. I was thinking that the two of us talking about this is a little bit of physician heal thyself. Because I think, arguably, the places where we spend time are the most extreme manifestations of the dynamic that Elisabeth is observing. For sure, in most mainstream media organizations, it would be very hard for you to ever say a word if you were a Republican. In some very mainstream news organizations, you’d be excommunicated, you’d be canceled. You’d be regarded as somebody who needed to be deplatformed for the mere fact that you had harbored Republican beliefs.

And I think that probably does more damage than a random company being political or being politicized. And, of course, my perspective on this is clear. I say it does damage because I actually think we do need to deal with views we don’t like and encounter views we don’t like and wrestle with it. And we would be in a much healthier place if we could do that.

And then, you think about academia, and the role it plays in shaping the way young people think. And it’s probably not accidental that colleges and universities are hotbeds of woke behavior, given that all the professors feel the same way.

Luigi: So, Bethany, you gave me an idea, since this is going to be the last episode for the year. Besides a happy holidays to all our listeners, I think I want to suggest a New Year’s resolution for all of us, which is to befriend an ideological opponent. I think, for the new year, for 2022, our goal is to befriend some opponents. And we’re going to start with some radical guests on our podcast.

Bethany: I like the idea of having radical guests on our podcast. I think befriending might be an aggressive ask for many people. Maybe not befriend, but how about interact with your family members who have radically different views than you do? And instead of shutting down the conversation or storming off, maybe attempt a conversation with that relative. I’m going to talk to my mother this holiday season.

In mid-December, Italy’s antitrust regulator fined Amazon $1.3 billion.

Speaker 8: It’s one of the biggest-ever penalties imposed on a US tech giant in Europe. The country’s antitrust watchdog said Amazon had hurt competing operators in the ecommerce logistics market.

Bethany: The argument is that Amazon harmed competitors by favoring third-party sellers that also use the company’s logistics services. It’s a big salvo and one that may have some interesting repercussions. Amazon, of course, says that it’s done absolutely nothing wrong. So, Luigi and I thought that we would discuss Italy’s move as today’s Capital-is or Capitalisn’t.

Luigi: What I found interesting about that fine is that it is not the typical attack that you see in the United States. This is because Amazon was using the logistics infrastructure as a discriminating factor for other competitors. And if they didn’t use their logistics infrastructure, they wouldn’t be presented in the right way on the website, they wouldn’t be given the right priority, and so on and so forth. So, it’s very much in the spirit of trying to create an equal marketplace online.

Bethany: I don’t know, though, because it does put Amazon in this category just based on its size of saying that Amazon has to be fair. The reality is, if you go to a clothing store and you’re a really good customer because you buy one of everything, then chances are you might get special discounts sometimes. So, isn’t that within a company’s purview to be able to say, “Hey, you use more than one of my services; therefore, I’m going to give you better deals”? That’s the way capitalism has always worked. Better customers get better deals.

Maybe a better example than the clothing store is that big traders on Wall Street have always gotten preferential treatment over the little guy who might be trading 50 or 100 shares. They’ve always gotten better pricing, better insight, better calls, because size buys you something.

Luigi: Bethany, you touched on a very sensitive topic in the entire antitrust debate, because there is a law on the books called Robinson-Patman that basically prohibits, in the United States, making those kinds of discriminatory discounts. However, this law is not applied. It’s not applied because the economists have decided it doesn’t make sense.

Now, it’s a bit of a contradiction, because there’s a law on the books. Actually, they tried five times to repeal it in Congress, but they did not succeed in repealing it in Congress, because it’s very popular among average Americans, precisely because it helps small stores versus large ones.

It’s at the core of what is the role of antitrust? Because if you only think in terms of what is the best for customers, this might be good, because you get lower prices. If you are concerned also about the ability of alternatives to survive, because alternatives provide opportunities maybe to ethnic minorities, maybe to religious minorities, maybe to people with different tastes or whatever, then you are trying to protect the number of competitors, not necessarily consumers. And that’s what the dominant view of antitrust, which is based on consumer welfare, is against. So, this is really at the core of the debate, what the antitrust law should be about.

Bethany: That’s really interesting. I had no idea there was even such a law on the books. Because the reality is this law is broken all the time in every aspect of life. Think about the special benefits that the people who pay more to go on a cruise get over the other ones. I’ve only read about this, I’ve never been on a cruise. I feel like I need to say that.

But nonetheless, I guess, if you spend a lot of money on a cruise, you get special access. There are parts of the ship that the other people, the plebeians, don’t get to trespass on. And so, this works in every aspect of our life. The more you pay, the better a customer you are, the more you get. So, why should business have to operate by a different standard?

Luigi: Because here there is an important nuance, the fact that there is an aspect which has the characteristic of natural monopoly. So, if you have, for example, logistics, the very dispersed infrastructure of transportation tends to be a natural monopoly, so much so that in the past and even today, in the United States, there is a postal service run by the state, and in many countries, the postal service was managed by the state because of that natural monopoly.

So. when you are using price discrimination in your natural monopoly to favor or disfavor somebody, then you’re really impacting competition in a major way. After all, this is what Rockefeller was accused of having done with the railways. He had signed deals with the railways so that his competitors would not get the same price that he would get. So, he put them all out of business. And he put them out of business, not because he was more efficient. He was probably more efficient, but he put them out of business because of these deals.

Bethany: On that note, as we get to Capital-is or Capitalisn’t, I’m going to call the European ruling a Capital-is, because I think trying to figure out these issues and trying to figure out where we draw the line is one of the most important issues the business and the regulatory world faces. So, even if we disagree about where the line should be set, it clearly shouldn’t be set in the place that Amazon is the only company left in the world.

Luigi: And because we are approaching Christmas, I will have to agree with you, but with one correction. It is actually an Italian ruling, not a European ruling.

Bethany: I’m sorry. Oh, no. Dear God.

Luigi: It’s not incorrect, because Italy is part of Europe for the moment. But I think that . . .

Bethany: Then I’d like to offer up a caveat, too, which is that if anybody at Amazon listens to our podcast, I still want the things I ordered, damn it.

Luigi: And I want them by Christmas.

Bethany: Exactly. Happy holidays, everybody.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.