The revolution that’s been happening in financial services is right in your pocket: the phone that you pull out when the check arrives after a restaurant dinner with friends. Until relatively recently, each diner would root around for their wallet. Now, one person typically charges the entire amount on their card (stored in their e-wallet on their phone) and everyone else uses their phones to send them cash.

Not only have peer-to-peer money transfers become easy, but many similar quotidian money chores are now fully digitized. You have automated bill pay. You check your credit card balances before making a big purchase. You move money easily from savings to investing accounts. There are tasks for which you might want to sit down at your computer instead, such as applying for a mortgage or rebalancing your portfolio—at which point you might consider getting professional advice through a robo-advisor that relies on algorithms to deliver advice tailored to your specific needs.

Over the past 15 years, technology has upended how people spend, save, borrow, and invest. The transformation—which has been equal parts gradual and astounding—actually began in the late 20th century, when consumers started checking bank balances and shopping online. Those first glimmers of financial technology, or fintech, were initially limited by snail-paced dial-up internet connectivity. But then came broadband, the smartphone, and a reliable wireless network that made it not just possible but easy to run our financial lives via mobile apps—or, when we’re feeling more old school, laptops and desktops with lightning-fast connectivity.

Fintech is now so pervasive that it can be easy to lose sight of the bigger picture, namely what it has introduced into and changed about the financial system. As we’ve become comfortable with Cash App, Venmo, and Zelle, ATMs and bank branches are disappearing. So-called shadow banks, many of which offer a fintech solution to a traditional service (such as mortgages), have grown to become significant lenders. Digital credit checks and advanced analytical tools assess prospective borrowers on a granular level, helping businesses better manage risks and deliver services more quickly. And these are likely still early days in terms of fintech’s upheaval: Global revenue from financial technology is projected by the Boston Consulting Group to grow from about $245 billion in 2021 to $1.5 trillion in 2030.

Rapid rise

A report finds that global revenue from fintech is set to grow more than sixfold between 2021 and 2030, driven largely by banking, with insurance also expanding.

Fintech has made life easier in many ways, yet as with any seismic change, there are trade-offs. Financial data coursing through the cloud raises the massive challenge of managing cybersecurity threats, with implications for systemic stability. But beyond that, a growing library of research focuses on a different area of the landscape, showing how discrete slices of early-stage fintech may be generating unintended consequences for consumers and the financial services industry. It is highlighting risks and potential new vulnerabilities, which are critical to understand in order to ensure consumers are protected and the financial system remains stable.

Bank deposits become less sticky

In the 1980s, Chicago Booth’s Douglas W. Diamond and Washington University in St. Louis’s Philip H. Dybvig developed a model for understanding the implicit mismatch in a traditional bank’s operations. Taking in short-term deposits that are balance-sheet liabilities and using them to make longer-term loans or securities is on its face a risky proposition that is the heart of traditional banking. In 2022, Diamond and Dybvig were awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for their findings, alongside former Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke for his work on bank fragility during financial crises. (For more, read “Bank Runs Aren’t Madness: This Model Explained Why.”)

If enough customers want to pull their short-term deposits at the same time and the bank can’t raise sufficient funds from its long-term assets, it can face a run if its balance-sheet stress becomes known. If enough banks experience this simultaneously, the financial system is at risk. As Diamond and Dybvig’s research explained, the “stickiness” of those deposits, their propensity to stay put and not move, is important. That stickiness, helped along by the introduction of federal deposit insurance after the Great Depression, has greatly reduced bank runs.

But there’s a new tech-driven wrench in this classic understanding of how banks operate. Digital banking by definition makes it ever easier to move money around, which suggests deposits may be less sticky—and that could make banks less stable.

Banking apps and high-speed internet connectivity arrived around the same time that the US Fed made it impossible to earn much on cash. From 2008 into early 2022 (with a few brief blips), the federal funds rate—the peg for short-term savings yields—was 0 percent. When the Fed finally lifted that rate in early 2022 and kept raising it to above 5 percent, researchers were able to see how consumers behaved when there was an incentive to move money around to earn a higher yield.

Deposits on the move

As the Fed increased rates, online banks responded quickly and drew in deposits, while brick-and-mortar banks were slower to react and saw outflows.

One observation is that the ease of bank transfers appears to have changed how the Fed’s monetary policy is absorbed in the market, suggests research by the Ohio State University’s Isil Erel, University of California at Irvine’s Jack Liebersohn, University of Cambridge’s Constantine Yannelis, and MIT PhD student Samuel Earnest.

Using the 2022–23 Fed rate tightening as their study period, the researchers document that every 100 basis point increase in that key rate prompted online banks to increase their deposit yield by an average of 30 basis points more than traditional banks. Those higher yields helped online banks attract more money, while total deposit levels at traditional banks (which remain vastly larger than online banks) fell.

The researchers suggest that policymakers need to account for this when making assumptions about the speed at and way in which monetary-policy changes will be absorbed in the economy.

Outflows could cause instability

A second observation is that the app-based ease of transfers may be destabilizing for banks that cater to tech-savvy customers. Stanford’s Naz Koont, Columbia’s Tano Santos, and Chicago Booth’s Luigi Zingales looked at banks that offer both a digital app and a brokerage unit. This type of bank makes it almost effortless to move money from a low-rate regular deposit account (savings or checking) to a higher-yielding money market mutual fund account whose interest tracks the federal funds rate. In contrast to digital banks, the researchers considered “traditional” banks to be those without a brokerage unit. Customers of traditional banks have a harder time moving money to higher-rate investments.

When the Fed started hiking interest rates in 2022, deposit growth slowed in both traditional and digital banks. Many customers, unhappy with low rates at their banks, looked for higher yields. But the drop was more pronounced at the digital banks, the researchers find, pointing to the ease with which customers could switch to a higher-yielding investment account.

When money is so easily moved, the intrinsic business value of deposits becomes less certain. The researchers estimate that the 425 basis point increase in the fed fund rate that occurred in 2022 decreased deposit growth at traditional banks by about 7 percent, and between roughly 11 percent and 32 percent at the digital banks. This suggests that stability becomes more of an issue in a world where rates are rising and digital banking is ever more popular.

The researchers have a nuanced take for how this affects the business value of deposits. They calculate that heightened sensitivity to rising rates for digital banks suggests a franchise value that is 12 percent lower than for traditional banks. When they also account for the fact that digital banks spend less to service their accounts, the impact on the banks’ franchise value is muted—but the deposit franchise value remains more sensitive to changes in the policy rate.

“Digitalization will progressively help depositors manage their money more efficiently, eliminating deposit stickiness and forcing banks to pay higher rates on deposits. These things are all good for depositors, but they will greatly diminish the value of the deposit franchise and its hedging properties, inducing problems of financial stability,” the researchers write.

Where fintech has shown up

Technology is helping households better manage their finances in a variety of ways.

Banking apps. While the footprint of online-only banks is still relatively small, even traditional banks are reducing their reliance on branches as more Americans have swapped making in-person visits for logging in to their bank apps. The number of commercial bank branches regulated by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation has declined from a peak of near 83,000 in 2012 to less than 70,000 today, according to the FDIC.

E-pay. The original consumer financial tech, the ATM, is in less demand as well. More than four in 10 people surveyed by the Pew Research Center in 2022 said none of their purchases in the prior week involved cash, up from a quarter in 2015. People turn instead to Apple Pay, Cash App, PayPal, Venmo, and other e-pay apps on their smartphone’s screen.

The 2023 failure of Silicon Valley Bank was in part an example of how fintech’s erosion of customer stickiness can have systemic consequences. SVB failed mostly because of its mistimed investment in long-term Treasurys ahead of Fed tightening that sharply reduced the market value of those bonds. As news began to circulate that SVB’s long-term assets were taking a hit, the bank’s customers could move their deposits easily. And unlike at most banks, a large portion of SVB deposits were uninsured, as wealthy customers and business clients kept more than the basic $250,000 limit for federal insurance.

SVB’s bad bond bets were the ultimate problem. But a takeaway from the March 2023 turmoil, which also saw Signature Bank fail and then First Republic follow in May, is that more aggressive regulatory oversight of digital banks may be necessary: No one should assume that deposits at these tech-forward banks will be as sticky in times of stress.

That’s the conclusion of Northwestern’s Efraim Benmelech and Notre Dame’s Jun Yang and Mical Zator, who note that between 2016 and 2022, US bank deposits nearly doubled amid a sharp decline in branches. Banks with fewer branches were able to expand without relying on brick-and-mortar locations. “Digital banking enabled banks to grow faster and attract uninsured deposits, but those large deposit inflows took the form of ‘hot money’ that changed its course when economic conditions worsened,” they write.

The changing nature of deposit stickiness in the digital age should spark a rethink of monetary policy, conclude Koont, Santos, and Zingales. In a world where the deposit franchise value is less reliable, a sharp and fast rise in interest rates—as seen in 2022—carries greater risk of causing bank insolvency, especially if the bank’s long-term portfolio is either illiquid or has lost value amid rising rates. “In such a world, the Fed has limits on its ability to raise interest rates fast. Thus, it cannot afford to fall behind the curve in fighting inflation because it cannot catch up fast,” the researchers write. “In sum, understanding the impact of digitalization on banking is essential for both regulation and monetary policy.”

Lending models may change

The business model of digital-forward banks may also be affecting lending strategies. And that in turn has ramifications for the balance-sheet risk of banks—and potentially for systemic stability, find University of California at Los Angeles’s Shohini Kundu, Tyler Muir, and Jinyuan Zhang.

The researchers note that nearly 20 years ago (before the Fed’s zero-rate regime), deposit rates among the 25 largest banks in the United States clustered fairly tightly, with a range of just 0.7 percentage points between the highest and lowest payers. That range is now about 3.5 percentage points, as the too-big-to-fail types (Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, and the like) pay close to zero while all-online players such as Ally pay more than 4 percent.

Digital-forward banks offering high deposit rates now have two distinct challenges, as the researchers document. They need to loan out money at a rate that exceeds the one they are paying depositors, and they need to compensate for the fact that those deposits are, as Benmelech, Yang, and Zator put it, “hot.” In a bid to address both challenges, digital banks tend to make shorter-term and higher-risk loans, such as car and personal loans, according to Kundu, Muir, and Zhang. And these loan areas have been a growing part of the overall consumer credit market: According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, nonhousing debt accounted for 21 percent of total consumer debt in 2008, and in early 2024, it was up to 28 percent.

Two paths for banks

Banks’ deposit rates (which affect lending decisions) moved in sync until 2015. After that, digital-first banks then kept pace with rising Fed rates, while others adjusted more slowly.

None of this has yet caused a problem. After all, the recent Fed tightening has occurred during an economic expansion, when consumer credit delinquencies and defaults are lower. Additionally, while past rate hikes have led to less lending, the flow of deposits to higher-rate banks (from lower-rate ones) allows those banks to continue apace with their specialized lending, the researchers argue.

That said, they note that today’s low charge-off rate—the percentage of loans written off as uncollectible—is more than triple for digital banks what it is for traditional ones, because digital banks hold a much larger share of these loans. Current capital ratios are the same for digital banks and traditional banks, despite their different lending risk profiles.

It’s unclear what may happen in a recession. The researchers land on a rough estimate that a 10 percent shift in deposits from banks paying low rates to high ones could increase the overall credit risk of the sector by 20 percent.

The cost of in-person banking goes up

Most people under the age of 40 have limited experience (and likely limited interest) in schlepping to a bank. However, plenty of older Americans prefer the brick-and-mortar experience, and in some communities, it’s getting harder to find that. For people who prefer in-person banking, the closure of bank branches can be a big deal, particularly in suburban and rural areas. Banks maintaining a branch presence have responded to the lower competition by raising fees and lowering deposit rates, some research suggests.

University of Southern California’s Erica Xuewei Jiang, Singapore Management University’s Gloria Yang Yu, and UCLA’s Zhang studied how the rollout of 3G technology that made robust mobile banking possible has affected bank branches. Between 2007 and 2018, there were twice as many branch closures in counties with more younger residents than in counties with a large older population, they find. They also calculate that banks that maintained their branches, facing less competition, paid lower rates on deposits and charged higher rates for mortgages, auto loans, and unsecured personal loans. This means that for consumers who want to bank in person, there’s now an associated extra cost.

Indian School of Business’s Jan Keil and University of Zurich’s Steven Ongena suggest another way in which technology may contribute to the demise of bank branches. Their study of US county-level branch closures from 1996 to 2020 acknowledges that consolidation was a big reason. But technology was a contributing factor. Branch closures were more strongly correlated in their data with overall bank budgets (the very budgets that make it possible to use technology to collect, process, and store information) than with consumer use of digital banking.

Data-sharing proliferates

While older, less digitally savvy consumers are losing options, the consumers at the other end of the spectrum face different challenges. It has become easier for banks and financial services firms to share data, with customer approval, as part of what is being billed as open banking. Many governments are aggressively pushing open-banking initiatives, hoping they will expand access to financial services.

Borrowing money or obtaining an insurance quote increasingly depends on letting a fintech app access your bank and credit data to assess your risk. For people with good credit, there is an inherent upside to sharing data: Their request is processed quickly and can be fine-tuned to their personal financial picture. The information-rich process also helps lenders better manage their operational risk, which is healthy for the financial system and could potentially lead to better rates for borrowers.

But this process can also lead to profiling, even and perhaps especially for people who opt out of data-sharing, suggests research by Stanford’s Zhiguo He, Texas A&M’s Jing Huang, and Yale’s Jidong Zhou. Even if consumers choose to hold their information close, algorithms can make inferences and apply those to a personal situation.

In the United Kingdom, the government pushed for early adoption of open banking. A study led by University of Maryland’s Tania Babina finds that open banking is positive for the fintech system—more data to crunch and monetize in direct offers to customers—but has trade-offs for consumers. On the one hand, open banking helps deliver more granular and personal advice that improves household finances, the researchers find. And consumers who opt into data-sharing are 10 percent more likely to be approved for a new credit card or personal loan.

But, echoing the theoretical concerns advanced by He, Huang, and Zhou, the researchers find that people who decline to share data are nonetheless affected. Their nonparticipation is read as a risk. “The act of opting out itself sends a signal from which lenders draw a negative inference. Moreover, these consumers are likely to be on the margins of the financial system, and thus precisely those whose financial inclusion policymakers are interested in facilitating,” the research team concludes.

In some cases, consumers on the margins may be burned by the opportunities that data-sharing presents. For example, open banking is the engine behind the rapid growth in “buy now, pay later” offerings. Many websites display a BNPL option (such as PayPal’s Pay in 4), and shoppers who click on it are run through a credit and financial check that takes only seconds. If approved, they can pay off their purchase in interest-free installments.

But the convenience of BNPL could lead to overspending and interest accrual. At the point of purchase, consumers applying for a BNPL offer must decide if they want to use a bank debit card or credit card to make the current and future payments. If they choose to use the debit card and are short funds in the future, they risk paying an overdraft fee. If they opt for the credit card, they could wind up having to pay interest of 20 percent or more.

Younger consumers in poorer areas tend to use credit cards for BNPL purchases more often than less financially disadvantaged consumers, according to Rice University’s Benedict Guttman-Kenney (a recent graduate of Booth’s PhD program) and University of Nottingham’s Chris Firth, a research fellow, and John Gathergood. In their sample of roughly 1 million consumer credit card accounts from the UK, they find that about 20 percent of transactions involved a BNPL purchase and that younger consumers accounted for 27 percent of credit card BNPL users. The researchers did not track repayment history but note the potential harm that may be building, namely that BNPL can be a gateway to credit card debt for people who can ill afford to run up unpaid balances. (For more on BNPL, read “The Hidden Costs of ‘Interest Free’ Payment Plans.”)

Mortgages get issued faster—at a cost

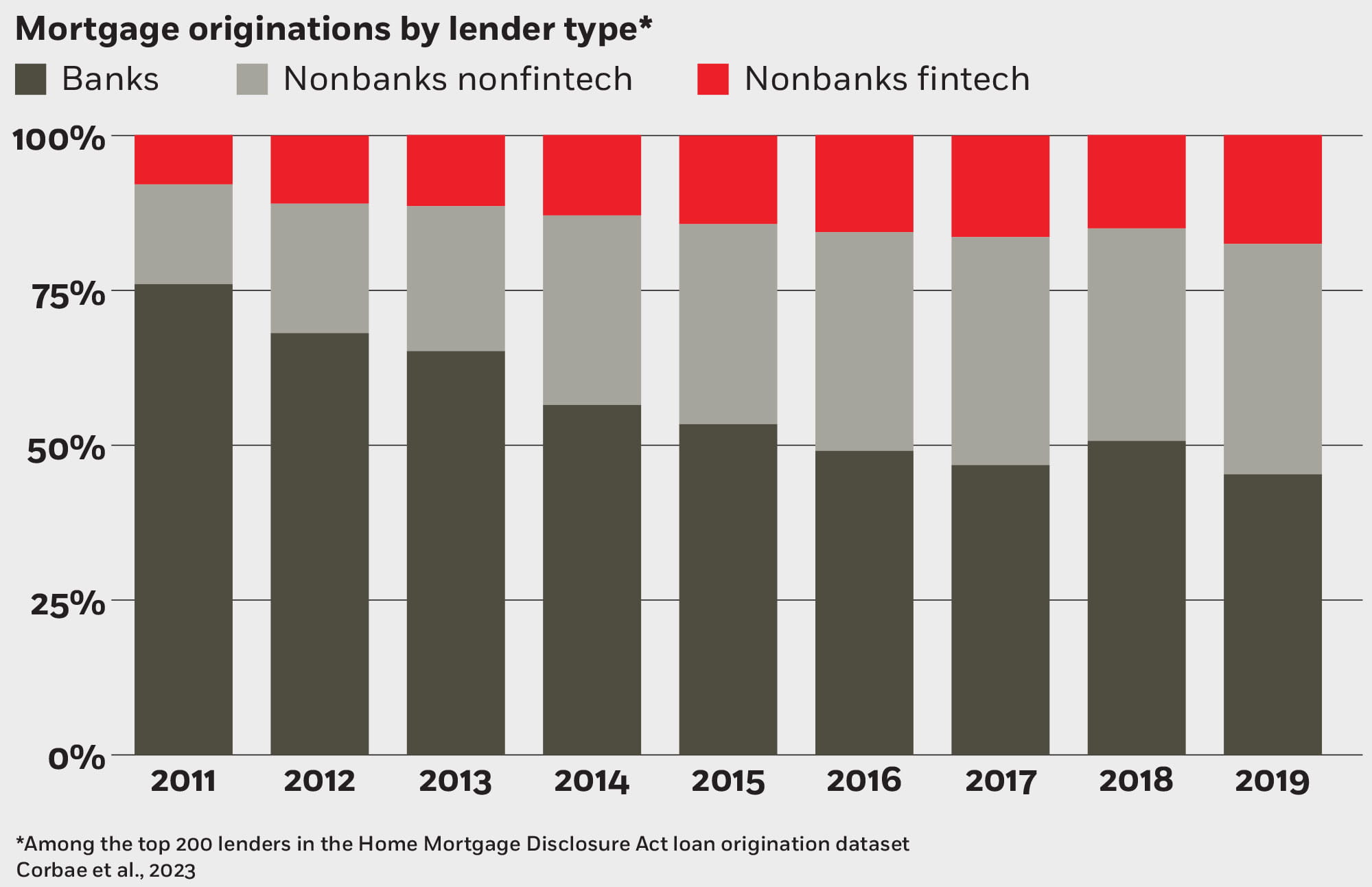

Fintech companies are now a significant subset of the shadow-banking industry, which itself has become a major force in residential mortgage lending in the US. An influential 2018 research paper—by Stanford’s Greg Buchak, Northwestern’s Gregor Matvos, Columbia’s Tomasz Piskorski, and Stanford’s Amit Seru—finds that between 2007 (before the mortgage meltdown central to the 2008–09 financial crisis) and 2015, shadow banking’s share of the mortgage market grew from less than 30 percent to 50 percent. By 2017, that share was 55 percent.

Fintech lenders’ market share in mortgage originations grew from 3 percent in 2007 to 12 percent in 2015, they find. By 2019, it was up to 17 percent, according to more recent research from University of Wisconsin’s Dean Corbae, the Philadelphia Federal Reserve’s Pablo D’Erasmo, and University of Arkansas’s Kuan Liu.

Fintechs loaned money to less risky customers, according to Buchak, Matvos, Piskorski, and Seru. Those good credit risks paid for the convenience, generally accepting higher interest rates for being able to close a mortgage online. (Corbae, D’Erasmo, and Liu find similar patterns in loan data running through 2019.)

The researchers estimate that about 35 percent of the growth in shadow-bank mortgage lending between 2007 and 2015 was due to technology, with “regulatory arbitrage” accounting for the rest of the growth, as shadow banks essentially circumvented the regulation of traditional banks.

And that regulatory arbitrage is a continuing concern. All shadow banks, fintech or not, are prohibited from accepting deposits. In the US, they are therefore exempt from a lot of federal regulation, as much of the bank system’s oversight is pegged to deposit-taking institutions.

But shadow banks nonetheless rely on support from the government, which both guarantees many mortgages and is a major buyer of the home loans that fintech lenders originate. The lack of deposits effectively means that shadow banks follow a vastly different business model than traditional banking, which uses short-term deposits to fund longer-term loans. Instead, these institutions, also known as nonbank banks, rely on income from originating loans and then packaging them as securities that are sold to investors—among these are mortgage-backed securities, of which the Fed is one of the main buyers, currently holding $2.2 trillion worth.

It’s possible to envision how this new fintech-fueled banking system could run into trouble. Online banks paying high deposit rates are motivated to focus on higher-risk lending to earn enough to cover their deposit payouts. The convenience with and speed at which credit decisions can be made at online checkouts may be too easy for many households.

Revolutions are typically messy affairs, whether they be political, cultural, or—in this case—financial. The fact is that fintech has revolutionized how we manage our money, and researchers are monitoring the industry’s continued growth, keen to the extent to which the financial system, and household financial stability, could become more fragile. As that work provides more clarity on unintended consequences, the next step will be to assess whether in this emerging fintech era, the guardrails we currently rely on to provide structure, fairness, and protection for banking consumers will have to evolve as well.

- Tania Babina, Saleem A. Bahaj, Greg Buchak, Filippo De Marco, Angus K. Foulis, Will Gornall, Francesco Mazzola, and Tong Yu, “Customer Data Access and Fintech Entry: Early Evidence from Open Banking,” Journal of Financial Economics, forthcoming.

- Efraim Benmelech, Jun Yang, and Mical Zator, “Bank Branch Density and Bank Runs,” Working paper, July 2023.

- Boston Consulting Group, “Global Fintech 2023: Reimagining the Future of Finance,” May 2023.

- Greg Buchak, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, and Amit Seru, “Fintech, Regulatory Arbitrage, and the Rise of Shadow Banks,” Journal of Financial Economics, December 2018.

- Dean Corbae, Pablo D’Erasmo, and Kuan Liu, “Market Concentration in Fintech,” Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia working paper, June 2023.

- Douglas W. Diamond and Philip H. Dybvig, “Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity,” Journal of Political Economy, June 1983.

- Isil Erel, Jack Liebersohn, Constantine Yannelis, and Samuel Earnest, “Monetary Policy Transmission Through Online Banks,” Working paper, May 2024.

- Benedict Guttman-Kenney, Chris Firth, and John Gathergood, “Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) . . . on Your Credit Card,” Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, March 2023.

- Zhiguo He, Jing Huang, and Jidong Zhou, “Open Banking: Credit Market Competition When Borrowers Own the Data,” Journal of Financial Economics, February 2023.

- Erica Xuewei Jiang, Gloria Yang Yu, and Jinyuan Zhang, “Bank Competition amid Digital Disruption: Implications for Financial Inclusion,” Working paper, August 2023.

- Jan Keil and Steven Ongena, “The Demise of Branch Banking—Technology, Consolidation, Bank Fragility,” Journal of Banking and Finance, January 2014.

- Naz Koont, Tano Santos, and Luigi Zingales, “The Impact of Digitalization on Bank Stability,” Working paper, April 2025.

- Shohini Kundu, Tyler Muir, and Jinyuan Zhang, “Diverging Banking Sector: New Facts and Macro Implications,” Working paper, October 2024.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.